This is the first entry in a new series called "Unsullied by Falsehood" exploring assumptions, mistakes, and legends in the history of the Declaration of Independence. The series title is inspired by a cut phrase from the Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence: "To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world, for the truth of which we pledge a faith yet unsullied by falsehood."

This is the first entry in a new series called "Unsullied by Falsehood" exploring assumptions, mistakes, and legends in the history of the Declaration of Independence. The series title is inspired by a cut phrase from the Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence: "To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world, for the truth of which we pledge a faith yet unsullied by falsehood."

As we near July 4th and the 240th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a familiar image will circulate and pop up in the minds of most Americans.

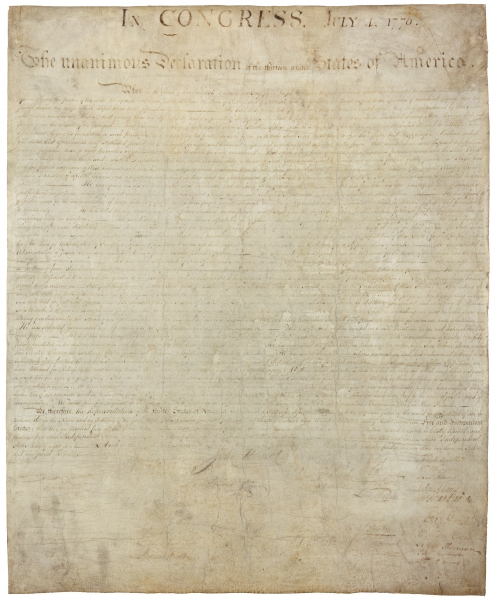

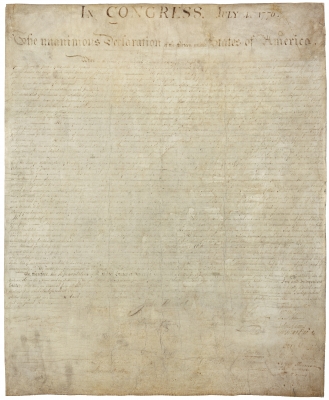

This is not the original parchment of the Declaration of Independence, engrossed by Timothy Matlack and signed by 56 delegates. Today, that parchment looks like this:

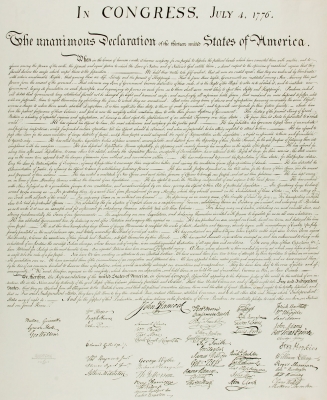

The clearer, crisper image is actually an engraving made by William J. Stone in 1823. It is generally accepted that the Stone engraving is an exact facsimile of the original parchment, because Stone used the original to create his engraving. His method of reproducing the engrossed and signed parchment has been the topic of heated debate -- some believe he used a wet transfer process, which removed ink from the original parchment and worsened its already-faded condition, some believe he was a skilled enough engraver to use other copying methods. Regardless, the Stone engraving has usurped the original parchment in our collective imagination as the image of the Declaration of Independence.

However, closer examination of the engrossed and signed parchment reveals that the Stone engraving is not an exact facsimile of the original parchment.

In December 1941, after Pearl Harbor, the Declaration of Independence and other founding documents were moved from their then-home at the Library of Congress to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where they remained until after the war. In May 1942, conservation specialist George L. Stout was brought to Fort Knox to inspect the condition of these documents. At that time, Stout was head of conservation at Harvard's Fogg Art Museum; soon after, he joined the Twelfth Army Group and was recruited for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archive section (he is a a principal character in Robert M. Edsel's The Monuments Men, and George Clooney played a character loosely based on Stout in the movie adaptation of the book).

George L. Stout, center, recovering the Bruges Madonna in 1945

George L. Stout, center, recovering the Bruges Madonna in 1945

Some of the best images we have of the engrossed and signed parchment of the Declaration of Independence were taken by George Stout in Fort Knox. He took wide shots, close-ups, used different lighting levels, and took before-and-after shots of his conservation of the documents to create a comprehensive cache of photographs, now stored at the Library of Congress (Archives PIO Series, Item #2556). One of his photographs is available to view and download in the Library's Online Catalog.

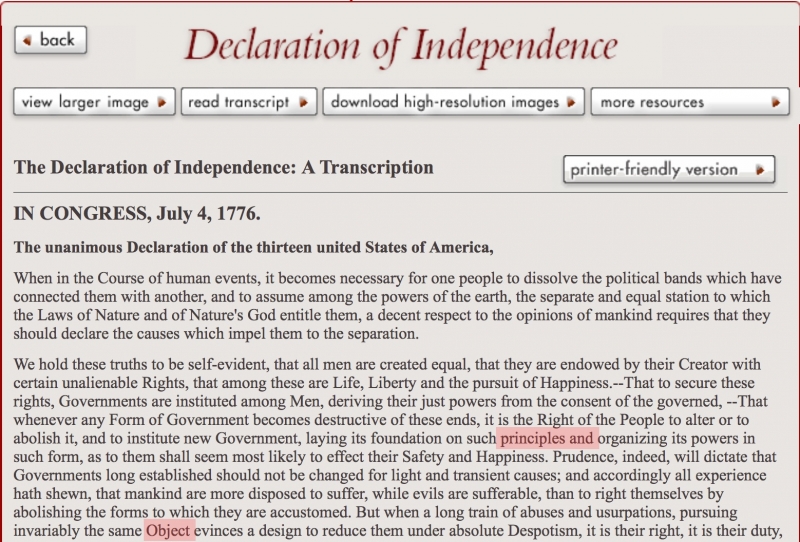

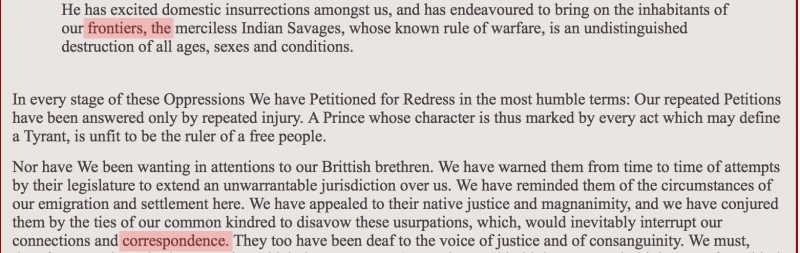

By comparing Stout's photographs, as well as a 1903 photograph taken by Levin C. Handy, to the William J. Stone engraving, we have found four examples of punctuation present in the engrossed and signed parchment and missing or different on the Stone engraving, and further research may reveal more discrepancies. These examples prove that, contrary to the popular assumption, the William J. Stone engraving of the Declaration of Independence is not an exact facsimile of the engrossed and signed parchment.

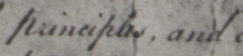

Example 1: Comma following principles in "laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form"

L-R: Handy Photograph, Stout Photograph, Stone Engraving

Example 2: Comma following object in "pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism,"

L-R: Handy Photograph, Stout Photograph, Stone Engraving

Example 3: Semicolon (not comma) following frontiers in "and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian Savages,"

L-R: Handy Photograph, Stout Photograph, Stone Engraving

Example 4: Period at the conclusion of "which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence"

![]()

L-R: Handy Photograph, Stout Photograph, Stone Engraving

The National Archives official transcription of the Declaration of Independence -- the top search result for the text of the Declaration -- is not labelled on the NARA website with an identification of its source text. Based on our examination, it appears that the William J. Stone engraving, not the original engrossed and signed parchment, is the basis for NARA’s published transcription. The transcription follows the Stone engraving in all but one of these examples; in example 4, the NARA transcription includes a logical period that is not actually present in the Stone engraving. (Update, November 2016: See note)

In addition to these punctuation discrepancies, we have found seven letter "i"s missing dots and five letter "t"s missing crossbars in the Stone engraving. These errors could provide insight into the method Stone used to create his engraving, or they could be simple engraver's errors.

Examples of missing i dot and missing t crossbar in Stone Engraving

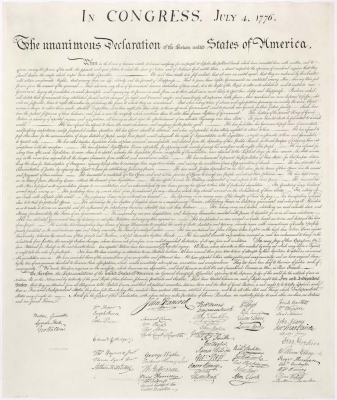

If you are looking for a truly exact facsimile of the engrossed and signed parchment this 4th of July, your best bet is a 1936 engraving by E.M. Weeks. On the order of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Weeks created a steel plate engraving based on the 1903 Handy photograph of the original parchment. He apparently spent over 1300 hours working on his facsimile, and his dedication is apparent: the Weeks engraving matches the original parchment in all of the examples listed above.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

So the next time you see an image of the Declaration of Independence, ask yourself: is this the original document, an exact facsimile, or a pretty close facsimile?

L-R: Original (engrossed and signed parchment); very close facsimile (1936 Weeks engraving); pretty close facsimile (1823 Stone engraving)

Credits:

- "Negative copied by LC Photoduplication Laboratory Oct. 12, 1944, from print made by L.C. Handy from his negative of April 24, 1903, when he photographed the engrossed and signed copy of the Declaration of Independence at the Dept. of State.", Library of Congress, LC-USP6-1121-A

- "Declaration of Independence, Photographed May 16, 1942 by Dr. George L. Stout, Honorary Consultant in the Care of Manuscripts & Parchments...", Library of Congress, LC-USP6-8061m

- Weeks Engraving taken from March 2015 Heritage Auctions Lot #93172

- Image of George L. Stout, National Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Update: The transcription screenshot was taken in May 2016. As of November 2016, the National Archives website has been updated, and the transcription is available here, with the following note: "The following text is a transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum.) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original."

By Emily Sneff

Unsullied by Falsehood | Next