In February 1790, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote a letter to John Adams, disparaging the histories of the American Revolution that had been written thus far: "Had I leisure, I would endeavor to rescue those characters from Oblivion, and give them the first place in the temple of liberty. What trash may we not suppose has been handed down to us from Antiquity, when we detect such errors, and prejudices in the history of events of which we have been eye witnesses, & in which we have been actors?" John Adams felt much the same, lamenting in his response written in April, "The History of our Revolution will be one continued Lye from one End to the other. The Essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklins electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod--and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War. These underscored Lines contain the whole Fable Plot and Catastrophy."

In February 1790, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote a letter to John Adams, disparaging the histories of the American Revolution that had been written thus far: "Had I leisure, I would endeavor to rescue those characters from Oblivion, and give them the first place in the temple of liberty. What trash may we not suppose has been handed down to us from Antiquity, when we detect such errors, and prejudices in the history of events of which we have been eye witnesses, & in which we have been actors?" John Adams felt much the same, lamenting in his response written in April, "The History of our Revolution will be one continued Lye from one End to the other. The Essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklins electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod--and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War. These underscored Lines contain the whole Fable Plot and Catastrophy."

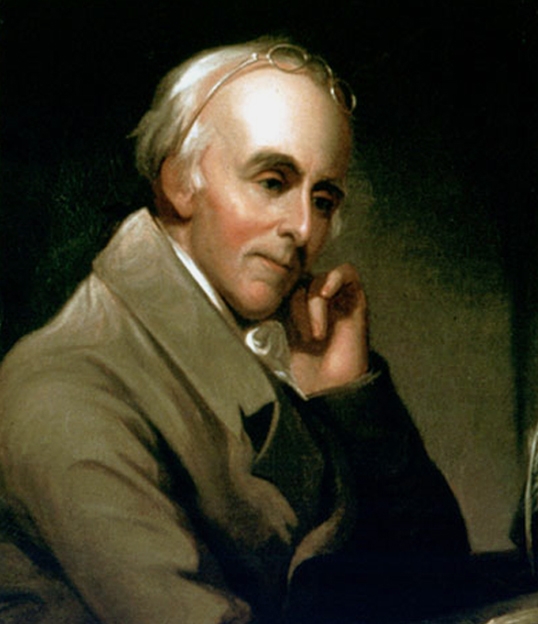

In the context of this conversation, Rush informed Adams that he had written "characters of the members of Congress who subscribed the declaration of independence." These characters are a part of Rush's autobiography, Travels Through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush, which was completed around 1800. The autobiography was intended for Rush's children and was later published, but in 1790, Rush offered Adams a glimpse.

In the context of this conversation, Rush informed Adams that he had written "characters of the members of Congress who subscribed the declaration of independence." These characters are a part of Rush's autobiography, Travels Through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush, which was completed around 1800. The autobiography was intended for Rush's children and was later published, but in 1790, Rush offered Adams a glimpse.

Rush first sent his friend Adams the description he had written of Robert Treat Paine, which Adams described as "very well and very just." As for Rush's description of Adams? First, Rush claimed that his character descriptions had been written during the war, but that "some additions have been made to them since, which were suggested by subsequent events." This is nowhere more true than in his description of John Adams. Take a look for yourself (and fear not, his other characters are brief by comparison):

![]() John Adams: He was a distant relation of Samuel Adams, but possessed another species of character. He had been educated a lawyer, and stood high in his profession in his native State. He was a most sensible and forcible speaker. Every member of Congress in 1776 acknowledged him to be the first man in the house. Dr. Brownson (of Georgia) used to say when he spoke, he fancied an angel was let down from heaven to illumine the Congress. He saw the whole of a subject at a single glance, and by a happy union of the powers of reasoning and persuasion often succeeded in carrying measures which were at first sight of an unpopular nature. His replies to reflections upon himself or upon the New England States were replete with the most poignant humour or satire. I sat next to him while Gen'l. Sullivan was delivering a request to Congress from Lord Howe for an interview with a committee of the house in their private capacities, after the defeat of the American Army on Long Island on the 26 of August 1776. Mr. Adams under a sudden impression and dread of the consequence of the measure, whispered to me a wish "that the first ball that had been fired on the day of the defeat of our Army had gone through his head." When he rose to speak against the proposed interview, he called Gen'l. Sullivan a "decoy duck whom Lord Howe has sent among us to seduce us into a renunciation of our independence." In a debate in which Mr. ---- criminator the New England troops as the principal cause of the failure of the expedition into Canada in 1775, he said, "the cause of the failure of that expedition was chiefly to be ascribed to the imprudence of the gentleman from Maryland who had fomented jealousies and quarrels between the troops from the New England and Southern States, in his visit to Canada, and (said Mr. Adams) if he were now penetrated, as he ought to be, with a sense of his improper and wicked conduct, he would fall down upon his knees, on this floor, and ask our forgiveness. He would afterwards retire with shame, and spend the remainder of his life in sackcloth and ashes, deploring the mischief he has done his country." He was equally fearless of men and of the consequences of a bold assertion of his opinions in all his speeches. Upon a motion in Congress Feb. 19th 1777 to surrender up to Gen'l. Washington the power of appointing his general officers, he said in opposition to it. "There are certain principles which follow us through life, and none more certainly than the love of the first place. We see it in the forms on which children sit at schools. It prevails equally to the latest period of life. I am sorry to see it prevail to little in this house. I have been distressed to see some of our members disposed to idolize the image which their own hands have molten. I speak here of the superstitious veneration which is paid to Gen'l. Washington. I honour him for his good qualities, but in this house I feel myself his superior. In private life I shall always acknowledge him to be mine." He wrote much as well as spoke often and copiously in favor of the liberties of his country. All his publications and particularly his letter to Mr. Wythe, containing a plan of a constitution for Virginia, discover a strong predilection for republican forms of government. To be safe, powerful and durable he always urged that they should be composed of three legislative branches, but that each of them should be the offspring directly or indirectly of the suffrages of the people. So great was his disapprobation of a government composed of a single legislature, that he said to me upon reading the first constitution of Pennsylvania. "The people of your State will sooner or later fall upon their knees to the King of Great Britain to take them again under his protection to deliver them from the tyranny of their own government." I could mention many conversations with him in which he appeared to be actuated by the highest tone of a republican temper as well as principles. When Congress agreed to send commissioners to France and endeavour to make a treaty with her, I asked him at his lodgings what he thought of Mr. ---- as a commissioner. "I would not vote for him (said he) above any man. He idolizes monarchy in his heart, and the first thing he would do when he arrived in France, would be to fall upon his knees and worship the King of France." The independence of the United States was first brought before the public mind in 1775 by a letter from him to one of his friends in Massachusetts that was intercepted and published in Boston in which he expressed a wish for that measure. It exposed him to the execrations of all the prudent and moderate people in America, insomuch that he was treated with neglect by many of his old friends. I saw this profound and enlightened patriot who in the year 1798 was admired and celebrated in prose and verse by the first citizens in Philadelphia, walk our streets alone after the publication of his intercepted letter in our newspapers in 1775 an object of nearly universal detestation. Events soon justified the wish contained in his letter, after which he rose in the public estimation, so as to become in the subsequent years of the revolution in some measure the oracle of the Whigs. He was a stranger to dissimulation, and appeared to be more jealous of his reputation for integrity, than for talents or knowledge. He was strictly moral and at all times respectful to religion. In speaking to me of the probable issue of the war, he said to me, in Baltimore in the winter of 1777; "We shall succeed in our struggle, provided we repent of our sins and forsake them," and then added, "I will see it out, or go to Heaven in its ruins." He possessed more learning probably, both ancient and modern, than any man who subscribed the declaration of independence. His reading was various. Even the old English poets were familiar to him. He once told me he had read all Bolingbroke's works with great attention. He admired nothing in them but the style and to acquire it, he said he had when a young man, transcribed his "ideas of a patriot king." When he went to Holland to negotiate a treaty with that country, he left a blank in Congress. I can say but little of his public conduct while he was in Europe, but that he was able, faithful and successful in all the business that was committed to him. I cannot conclude this account of Mr. Adams without expressing my obligations to him for the friendship with which he honoured me during the whole of his public life from 1774 to 1800. I possess a large collection of his letters written to me in Europe and America which I prize as records of his genius and patriotism. There was no diminution of our intimacy after he became President of the United States, nor did his high stations preclude controversy between us, on subjects upon which we differed, especially while he was President. Many delightful evenings have I passed at his house, in listening to the details of his public situations at home and abroad, and to anecdotes of public men. The pleasure of these evenings was much enhanced by the society of Mrs. Adams, who in point of talents, knowledge, virtue and female accomplishments, was in every respect fitted to be the friend and companion of her husband in all his different and successive stations, of private citizen, member of Congress, foreign Minister, Vice President and President of the United States.

John Adams: He was a distant relation of Samuel Adams, but possessed another species of character. He had been educated a lawyer, and stood high in his profession in his native State. He was a most sensible and forcible speaker. Every member of Congress in 1776 acknowledged him to be the first man in the house. Dr. Brownson (of Georgia) used to say when he spoke, he fancied an angel was let down from heaven to illumine the Congress. He saw the whole of a subject at a single glance, and by a happy union of the powers of reasoning and persuasion often succeeded in carrying measures which were at first sight of an unpopular nature. His replies to reflections upon himself or upon the New England States were replete with the most poignant humour or satire. I sat next to him while Gen'l. Sullivan was delivering a request to Congress from Lord Howe for an interview with a committee of the house in their private capacities, after the defeat of the American Army on Long Island on the 26 of August 1776. Mr. Adams under a sudden impression and dread of the consequence of the measure, whispered to me a wish "that the first ball that had been fired on the day of the defeat of our Army had gone through his head." When he rose to speak against the proposed interview, he called Gen'l. Sullivan a "decoy duck whom Lord Howe has sent among us to seduce us into a renunciation of our independence." In a debate in which Mr. ---- criminator the New England troops as the principal cause of the failure of the expedition into Canada in 1775, he said, "the cause of the failure of that expedition was chiefly to be ascribed to the imprudence of the gentleman from Maryland who had fomented jealousies and quarrels between the troops from the New England and Southern States, in his visit to Canada, and (said Mr. Adams) if he were now penetrated, as he ought to be, with a sense of his improper and wicked conduct, he would fall down upon his knees, on this floor, and ask our forgiveness. He would afterwards retire with shame, and spend the remainder of his life in sackcloth and ashes, deploring the mischief he has done his country." He was equally fearless of men and of the consequences of a bold assertion of his opinions in all his speeches. Upon a motion in Congress Feb. 19th 1777 to surrender up to Gen'l. Washington the power of appointing his general officers, he said in opposition to it. "There are certain principles which follow us through life, and none more certainly than the love of the first place. We see it in the forms on which children sit at schools. It prevails equally to the latest period of life. I am sorry to see it prevail to little in this house. I have been distressed to see some of our members disposed to idolize the image which their own hands have molten. I speak here of the superstitious veneration which is paid to Gen'l. Washington. I honour him for his good qualities, but in this house I feel myself his superior. In private life I shall always acknowledge him to be mine." He wrote much as well as spoke often and copiously in favor of the liberties of his country. All his publications and particularly his letter to Mr. Wythe, containing a plan of a constitution for Virginia, discover a strong predilection for republican forms of government. To be safe, powerful and durable he always urged that they should be composed of three legislative branches, but that each of them should be the offspring directly or indirectly of the suffrages of the people. So great was his disapprobation of a government composed of a single legislature, that he said to me upon reading the first constitution of Pennsylvania. "The people of your State will sooner or later fall upon their knees to the King of Great Britain to take them again under his protection to deliver them from the tyranny of their own government." I could mention many conversations with him in which he appeared to be actuated by the highest tone of a republican temper as well as principles. When Congress agreed to send commissioners to France and endeavour to make a treaty with her, I asked him at his lodgings what he thought of Mr. ---- as a commissioner. "I would not vote for him (said he) above any man. He idolizes monarchy in his heart, and the first thing he would do when he arrived in France, would be to fall upon his knees and worship the King of France." The independence of the United States was first brought before the public mind in 1775 by a letter from him to one of his friends in Massachusetts that was intercepted and published in Boston in which he expressed a wish for that measure. It exposed him to the execrations of all the prudent and moderate people in America, insomuch that he was treated with neglect by many of his old friends. I saw this profound and enlightened patriot who in the year 1798 was admired and celebrated in prose and verse by the first citizens in Philadelphia, walk our streets alone after the publication of his intercepted letter in our newspapers in 1775 an object of nearly universal detestation. Events soon justified the wish contained in his letter, after which he rose in the public estimation, so as to become in the subsequent years of the revolution in some measure the oracle of the Whigs. He was a stranger to dissimulation, and appeared to be more jealous of his reputation for integrity, than for talents or knowledge. He was strictly moral and at all times respectful to religion. In speaking to me of the probable issue of the war, he said to me, in Baltimore in the winter of 1777; "We shall succeed in our struggle, provided we repent of our sins and forsake them," and then added, "I will see it out, or go to Heaven in its ruins." He possessed more learning probably, both ancient and modern, than any man who subscribed the declaration of independence. His reading was various. Even the old English poets were familiar to him. He once told me he had read all Bolingbroke's works with great attention. He admired nothing in them but the style and to acquire it, he said he had when a young man, transcribed his "ideas of a patriot king." When he went to Holland to negotiate a treaty with that country, he left a blank in Congress. I can say but little of his public conduct while he was in Europe, but that he was able, faithful and successful in all the business that was committed to him. I cannot conclude this account of Mr. Adams without expressing my obligations to him for the friendship with which he honoured me during the whole of his public life from 1774 to 1800. I possess a large collection of his letters written to me in Europe and America which I prize as records of his genius and patriotism. There was no diminution of our intimacy after he became President of the United States, nor did his high stations preclude controversy between us, on subjects upon which we differed, especially while he was President. Many delightful evenings have I passed at his house, in listening to the details of his public situations at home and abroad, and to anecdotes of public men. The pleasure of these evenings was much enhanced by the society of Mrs. Adams, who in point of talents, knowledge, virtue and female accomplishments, was in every respect fitted to be the friend and companion of her husband in all his different and successive stations, of private citizen, member of Congress, foreign Minister, Vice President and President of the United States.

When Adams requested for Rush to send him his character, Adams expressed, "I know very well it must be a partial Panegyrick. I will Send you my Criticisms upon it. You know I have no affectation of Modesty." After seeing Rush's description of him, Adams wrote to his friend, "Your Letter of April 13 Soars above the visible diurnal sphere... How many Follies and indiscreet speeches do your minutes in your Note Book bring to my Recollection, which I had forgotten forever? Alass I fear I am not yet much more prudent." Adams sent no criticisms, so Rush made no alterations to his character. As it stands, his description of Adams is over 1300 words in length, and far more detailed than what Rush wrote for any other delegate; it even includes a brief but glowing sketch of Adams' wife Abigail.

Now, take a look at the rest of Rush's characters. Keep in mind -- Rush had a tendency to misremember (he was not alone in this), and exaggerate certain events. But generally, Rush accomplished his goal of highlighting Founding Fathers not named Washington or Franklin, and giving us a glimpse into the emotions and atmosphere of the Continental Congress. Rush is also an entertaining writer, so we have bolded noteworthy passages.

Josiah Bartlett: A practitioner of physic, of excellent character, and strongly attached to the liberties of his country.

Josiah Bartlett: A practitioner of physic, of excellent character, and strongly attached to the liberties of his country.

William Whipple: An old sea captain, but liberal in his principles and manners, and a genuine friend to liberty and independence.

William Whipple: An old sea captain, but liberal in his principles and manners, and a genuine friend to liberty and independence.

Matthew Thornton: A practitioner of physic, of Irish extraction. He abounded in anecdotes, and was for the most part happy in the application of them. He was ignorant of the world, but was believed to be a sincere patriot and an honest man.

Matthew Thornton: A practitioner of physic, of Irish extraction. He abounded in anecdotes, and was for the most part happy in the application of them. He was ignorant of the world, but was believed to be a sincere patriot and an honest man.

John Hancock: He was a man of plain understanding and good education. He was fond of the ceremonies of public life, but wanted industry and punctuality in business. His conversation was desultory, and his manners much influenced by frequent attacks of the gout which gave a hypochondriacal peevishness to his temper. With all these infirmities, he was a disinterested patriot, and made large sacrifices of an ample estate to the liberties and independence of his country.

![]() Samuel Adams: He was near sixty years of age when he took his seat in Congress, but possessed all the vigor of mind of a young man of five and twenty. He was a republican in principle and manners. He once acknowledged to me "that the independence of the United States upon Great Britain had been the first wish of his heart for seven years before the war." About the same time he said to me, "if it were revealed that 999 Americans out of 1000 would perish in a war for liberty, he would vote for that war, rather than see his country enslaved. The survivors in such a war, though few, (he said) would propagate a nation of freemen." He abhorred a standing army, and used to say they were the "shoe-blacks of society." He dreaded the undue influence of an individual in a republic, and once said to me; "Let us beware of continental and state great men." He loved simplicity and economy in the administration of government and despised the appeals which are made to the eyes and ears of the common people in order to govern them. He considered national happiness and the public patronage of religion as inseparably connected, and so great was his regard for public worship as the means of promoting religion, that he constantly attended divine service in the German Church in Yorktown (while Congress sat there) when there was no service in their chapel, although he was ignorant of the German language. His morals were irreproachable, and even ambition and avarice the usual vices of politicians, seemed to have no place in his breast. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was active in preparing and doing business out of doors. In some parts of his conduct I have thought he discovered more of the prejudices of a Massachusetts man, than the liberal sentiments of a citizen of the United States. His abilities were considerable, and his knowledge extensive and correct upon revolutionary subjects, and both friends and enemies agree in viewing him as one of the most active instruments of the American Revolution.

Samuel Adams: He was near sixty years of age when he took his seat in Congress, but possessed all the vigor of mind of a young man of five and twenty. He was a republican in principle and manners. He once acknowledged to me "that the independence of the United States upon Great Britain had been the first wish of his heart for seven years before the war." About the same time he said to me, "if it were revealed that 999 Americans out of 1000 would perish in a war for liberty, he would vote for that war, rather than see his country enslaved. The survivors in such a war, though few, (he said) would propagate a nation of freemen." He abhorred a standing army, and used to say they were the "shoe-blacks of society." He dreaded the undue influence of an individual in a republic, and once said to me; "Let us beware of continental and state great men." He loved simplicity and economy in the administration of government and despised the appeals which are made to the eyes and ears of the common people in order to govern them. He considered national happiness and the public patronage of religion as inseparably connected, and so great was his regard for public worship as the means of promoting religion, that he constantly attended divine service in the German Church in Yorktown (while Congress sat there) when there was no service in their chapel, although he was ignorant of the German language. His morals were irreproachable, and even ambition and avarice the usual vices of politicians, seemed to have no place in his breast. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was active in preparing and doing business out of doors. In some parts of his conduct I have thought he discovered more of the prejudices of a Massachusetts man, than the liberal sentiments of a citizen of the United States. His abilities were considerable, and his knowledge extensive and correct upon revolutionary subjects, and both friends and enemies agree in viewing him as one of the most active instruments of the American Revolution.

![]() Robert Treat Paine: He was educated a clergyman, and afterwards became a lawyer. He had a certain obliquity of understanding which prevented his seeing public objects in the same light in which they were seen by other people. He seldom proposed anything, but opposed nearly every measure that was proposed by other people, and hence got the name of "the objection maker" in Congress. His temper was amiable, and his speeches and conversation often facetious. He was moderate in his feelings for his country. This was so much the case, that he told me the first time I saw him in 1774 that his constituents considered him as one of their "cool devils." He was notwithstanding a firm, decided and persevering patriot and eminently useful in Congress particularly upon committees, in which he was remarkable for his regular and punctual attendance.

Robert Treat Paine: He was educated a clergyman, and afterwards became a lawyer. He had a certain obliquity of understanding which prevented his seeing public objects in the same light in which they were seen by other people. He seldom proposed anything, but opposed nearly every measure that was proposed by other people, and hence got the name of "the objection maker" in Congress. His temper was amiable, and his speeches and conversation often facetious. He was moderate in his feelings for his country. This was so much the case, that he told me the first time I saw him in 1774 that his constituents considered him as one of their "cool devils." He was notwithstanding a firm, decided and persevering patriot and eminently useful in Congress particularly upon committees, in which he was remarkable for his regular and punctual attendance.

Elbridge Gerry: He was a respectable young merchant, of a liberal education and considerable knowledge. He had no local or State prejudices. Every part of his conduct in 1775 & 1776 and 1777 indicated him to be a sensible, upright man, and a genuine friend to republican forms of government.

Elbridge Gerry: He was a respectable young merchant, of a liberal education and considerable knowledge. He had no local or State prejudices. Every part of his conduct in 1775 & 1776 and 1777 indicated him to be a sensible, upright man, and a genuine friend to republican forms of government.

William Ellery: A lawyer, somewhat cynical in his temper, but a faithful friend to the liberties of his country. He seldom spoke in Congress, but frequently amused himself in writing epigrams on the speakers which were generally witty and pertinent, and sometimes poetical. Mr. Paine had once given in a report in favor of purchasing some guns for the United States that were not bored. Some time after this, a motion was made to call upon the citizens of Philadelphia to furnish ready made clothes for the army, for materials to make them could not then be obtained in any of the stores. Mr. Paine opposed this motion, by holding up to the imagination the ridiculous figure our soldiers would make when paraded or marching in clothes of different lengths and colors. While he was speaking Mr. Ellery struck off with his pencil, the following lines. "Say, O! my muse--Why all this puzzle / Talk against long clothes, and give guns without a muzzle."

William Ellery: A lawyer, somewhat cynical in his temper, but a faithful friend to the liberties of his country. He seldom spoke in Congress, but frequently amused himself in writing epigrams on the speakers which were generally witty and pertinent, and sometimes poetical. Mr. Paine had once given in a report in favor of purchasing some guns for the United States that were not bored. Some time after this, a motion was made to call upon the citizens of Philadelphia to furnish ready made clothes for the army, for materials to make them could not then be obtained in any of the stores. Mr. Paine opposed this motion, by holding up to the imagination the ridiculous figure our soldiers would make when paraded or marching in clothes of different lengths and colors. While he was speaking Mr. Ellery struck off with his pencil, the following lines. "Say, O! my muse--Why all this puzzle / Talk against long clothes, and give guns without a muzzle."

Stephen Hopkins: A venerable old man of the Society of Friends, of an original understanding, extensive reading, and great integrity. He perfectly understood the principles of liberty and government and was warmly attached to the independence of his country. I once heard him say in 1776, "the liberties of America would be a cheap purchase with the loss of 100,000 lives!" He disliked hearing long letters from the Generals of our Army, and used to say "he never knew a General Quillman that was good for anything." As the result of close observation, he remarked to me in walking home from Congress, that he "had never known a modest man that was not brave."

Stephen Hopkins: A venerable old man of the Society of Friends, of an original understanding, extensive reading, and great integrity. He perfectly understood the principles of liberty and government and was warmly attached to the independence of his country. I once heard him say in 1776, "the liberties of America would be a cheap purchase with the loss of 100,000 lives!" He disliked hearing long letters from the Generals of our Army, and used to say "he never knew a General Quillman that was good for anything." As the result of close observation, he remarked to me in walking home from Congress, that he "had never known a modest man that was not brave."

Roger Sherman: A plain man of slender education. He taught himself mathematics, and afterwards acquired some property and a good deal of reputation by making almanacks. He was so regular in business, and so democratic in his principles that he was called by one of his friends "a republican machine." Patrick Henry asked him in 1774 why the people of Connecticut were more zealous in the cause of liberty than the people of the other States; he answered "because we have more to lose than any of them." "What is that," said Mr. Henry. "Our beloved charter," replied Mr. Shearman [sic]. He was not less distinguished for his piety, than his patriotism. He once objected to a motion for Congress sitting on Sunday upon an occasion which he thought did not require it, and gave as a reason for his object a regard for the commands of his Maker. Upon hearing of the defeat of the American army on Long Island, were they were entrenched and fortified by a chain of hills, he said to me, in coming out of Congress, "Truly in vain is salvation hoped for from the hills, and from the multitude of mountains."

Roger Sherman: A plain man of slender education. He taught himself mathematics, and afterwards acquired some property and a good deal of reputation by making almanacks. He was so regular in business, and so democratic in his principles that he was called by one of his friends "a republican machine." Patrick Henry asked him in 1774 why the people of Connecticut were more zealous in the cause of liberty than the people of the other States; he answered "because we have more to lose than any of them." "What is that," said Mr. Henry. "Our beloved charter," replied Mr. Shearman [sic]. He was not less distinguished for his piety, than his patriotism. He once objected to a motion for Congress sitting on Sunday upon an occasion which he thought did not require it, and gave as a reason for his object a regard for the commands of his Maker. Upon hearing of the defeat of the American army on Long Island, were they were entrenched and fortified by a chain of hills, he said to me, in coming out of Congress, "Truly in vain is salvation hoped for from the hills, and from the multitude of mountains."

![]() Samuel Huntington: A sensible, candid and worthy man, and wholly free from State prejudices.

Samuel Huntington: A sensible, candid and worthy man, and wholly free from State prejudices.

![]() William Williams: A well meaning man but often misled by State prejudices.

William Williams: A well meaning man but often misled by State prejudices.

![]() Oliver Wolcott: A worthy man of great modesty, and sincerely attached to the interests of his country.

Oliver Wolcott: A worthy man of great modesty, and sincerely attached to the interests of his country.

William Floyd: A mild and decided republican. He seldom spoke in Congress, but always voted with the zealous friends to liberty and independence.

William Floyd: A mild and decided republican. He seldom spoke in Congress, but always voted with the zealous friends to liberty and independence.

Philip Livingston: A blunt but honest man. He was supposed to be unfriendly to the declaration of independence, when it took place, but he concurred afterwards in all the measures that were adopted to support it. He was very useful in committees where a knowledge in figures on commercial subjects was required. A secret of Congress having transpired, he proposed that every member of Congress should declare upon oath that he had not divulged it, in order that the rascal (to use his own words) "might add the sin of perjury to that of treachery, and thereby damn his soul forever."

Philip Livingston: A blunt but honest man. He was supposed to be unfriendly to the declaration of independence, when it took place, but he concurred afterwards in all the measures that were adopted to support it. He was very useful in committees where a knowledge in figures on commercial subjects was required. A secret of Congress having transpired, he proposed that every member of Congress should declare upon oath that he had not divulged it, in order that the rascal (to use his own words) "might add the sin of perjury to that of treachery, and thereby damn his soul forever."

![]()

Francis Lewis: A moderate Whig, but a very honest man, and very useful in executive business.

![]() Lewis Morris: A cheerful, amiable man, and a most disinterested patriot. He had three sons at one time in the army, and suffered the loss of many thousand pounds by the depredations of the British army, upon his property near New York without repining. Every attachment of his heart yielded to his love of his country.

Lewis Morris: A cheerful, amiable man, and a most disinterested patriot. He had three sons at one time in the army, and suffered the loss of many thousand pounds by the depredations of the British army, upon his property near New York without repining. Every attachment of his heart yielded to his love of his country.

Richard Stockton: An enlightened politician, and a correct and graceful speaker. He was timid where bold measures were required, but was at all times sincerely devoted to the liberties of his country. He loved law, and order, and once offended his constituents by opposing the seizure of private property in an illegal manner by an officer of the army. He said after the treaty with France took place, "that the United States were placed in a more eligible situation by it, than they had been during their connection with Great Britain." His habits as a lawyer, and a Judge (which office he had filled under the British government) produced in him a respect for the British Constitution; but this did not lessen his attachment to the Independence of the United States.

Richard Stockton: An enlightened politician, and a correct and graceful speaker. He was timid where bold measures were required, but was at all times sincerely devoted to the liberties of his country. He loved law, and order, and once offended his constituents by opposing the seizure of private property in an illegal manner by an officer of the army. He said after the treaty with France took place, "that the United States were placed in a more eligible situation by it, than they had been during their connection with Great Britain." His habits as a lawyer, and a Judge (which office he had filled under the British government) produced in him a respect for the British Constitution; but this did not lessen his attachment to the Independence of the United States.

John Witherspoon: A well informed statesman, and remarkably luminous and correct in all his speeches. His influence was less than might have been expected from his abilities and knowledge owing in part to his ecclesiastical character. He was a zealous Whig, but free from the illiberality which sometimes accompanies zeal. In a report brought into Congress by a member from Virginia, George the 3d was called the "tyrant of Britain." Dr. Witherspoon objected to the word "tyrant," and moved to substitute king in its room. He gave as reasons for his objection, "That the epithet was both false and undignified. It was false, because George 3d was not a tyrant in Great Britain; on the contrary he was beloved and respected by his subjects in Great Britain, and perhaps the more, for making war upon us. It was undignified, because it did not become one sovereign power to abuse or use harsh epithets, when it spoke of another." The motion was negatived, and the amendment proposed by Dr. Witherspoon adopted.

John Witherspoon: A well informed statesman, and remarkably luminous and correct in all his speeches. His influence was less than might have been expected from his abilities and knowledge owing in part to his ecclesiastical character. He was a zealous Whig, but free from the illiberality which sometimes accompanies zeal. In a report brought into Congress by a member from Virginia, George the 3d was called the "tyrant of Britain." Dr. Witherspoon objected to the word "tyrant," and moved to substitute king in its room. He gave as reasons for his objection, "That the epithet was both false and undignified. It was false, because George 3d was not a tyrant in Great Britain; on the contrary he was beloved and respected by his subjects in Great Britain, and perhaps the more, for making war upon us. It was undignified, because it did not become one sovereign power to abuse or use harsh epithets, when it spoke of another." The motion was negatived, and the amendment proposed by Dr. Witherspoon adopted.

![]() Francis Hopkinson: An ingenious agreeable man. He took but a small part in the business of Congress, but served his country very essentially by many of his publications during the war.

Francis Hopkinson: An ingenious agreeable man. He took but a small part in the business of Congress, but served his country very essentially by many of his publications during the war.

![]() John Hart: A plain, honest, well-meaning Jersey farmer, with but little education, but with good sense and virtue enough to discover the true interests of his country.

John Hart: A plain, honest, well-meaning Jersey farmer, with but little education, but with good sense and virtue enough to discover the true interests of his country.

Abraham Clark: A sensible, but cynical man. He was uncommonly quick sighted in seeing the weakness and defects of public men and measures. He was attentive to business, and excelled in drawing up reports and resolutions. He was said to study more to please the people than to promote their real and permanent interests. He was warmly attached to the liberties and independence of his country.

Abraham Clark: A sensible, but cynical man. He was uncommonly quick sighted in seeing the weakness and defects of public men and measures. He was attentive to business, and excelled in drawing up reports and resolutions. He was said to study more to please the people than to promote their real and permanent interests. He was warmly attached to the liberties and independence of his country.

![]() Robert Morris: A bold, sensible, and agreeable speaker. His perceptions were quick and his judgments sound upon all subjects. He was opposed to the time (not the act) of the declaration of independence, but he yielded to no man in his exertions to support it, and a year after it took place, he publicly acknowledged on the floor of Congress, that he had been mistaken in his former opinion as to its time, and said that it would have been better for our country had it been declared sooner. He was candid and liberal in a debate, so as always to be respected by his opponents, and sometimes to offend the members of the party with whom he generally voted. By his extensive commercial knowledge and connections he rendered great services to his country in the beginning, and by the able manner in which he discharged the duties of financier, he revived and established her credit on the close of the revolution. In private life he was friendly, sincere, generous and charitable, but his peculiar manners deprived him of much of that popularity which usually follows great exploits of public and private virtue.

Robert Morris: A bold, sensible, and agreeable speaker. His perceptions were quick and his judgments sound upon all subjects. He was opposed to the time (not the act) of the declaration of independence, but he yielded to no man in his exertions to support it, and a year after it took place, he publicly acknowledged on the floor of Congress, that he had been mistaken in his former opinion as to its time, and said that it would have been better for our country had it been declared sooner. He was candid and liberal in a debate, so as always to be respected by his opponents, and sometimes to offend the members of the party with whom he generally voted. By his extensive commercial knowledge and connections he rendered great services to his country in the beginning, and by the able manner in which he discharged the duties of financier, he revived and established her credit on the close of the revolution. In private life he was friendly, sincere, generous and charitable, but his peculiar manners deprived him of much of that popularity which usually follows great exploits of public and private virtue.

Benjamin Franklin: He seldom spoke in Congress, but was useful in committees in which he was punctual and indefatigable. He was a firm republican, and treated kingly power at all times with ridicule and contempt. He early declared himself in favor of independence. John Adams used to say he was more of a philosopher than a politician. I sat next to him in Congress, when he was elected by the unanimous vote of every State in the Union to an embassy to the Court of France in the year 1776. When the vote was declared, I congratulated him upon it. He thanked me, and said "I am like the remnant of a piece of unsaleable cloth. You may have it, as the shopkeepers say, for what you please." He was then 70 years of age. His services to his country in effecting the treaty with France were highly appreciated at the time that event took place. He was treated with great respect by the French Court. A letter from Paris written while he was there, contained the following expressions. "Dr. Franklin seldom goes to Court, when he does he says but little, but what he says, flies by the next post to every part of the kingdom."

Benjamin Franklin: He seldom spoke in Congress, but was useful in committees in which he was punctual and indefatigable. He was a firm republican, and treated kingly power at all times with ridicule and contempt. He early declared himself in favor of independence. John Adams used to say he was more of a philosopher than a politician. I sat next to him in Congress, when he was elected by the unanimous vote of every State in the Union to an embassy to the Court of France in the year 1776. When the vote was declared, I congratulated him upon it. He thanked me, and said "I am like the remnant of a piece of unsaleable cloth. You may have it, as the shopkeepers say, for what you please." He was then 70 years of age. His services to his country in effecting the treaty with France were highly appreciated at the time that event took place. He was treated with great respect by the French Court. A letter from Paris written while he was there, contained the following expressions. "Dr. Franklin seldom goes to Court, when he does he says but little, but what he says, flies by the next post to every part of the kingdom."

Benjamin Rush*: He aimed well.

Benjamin Rush*: He aimed well.

*In his February 1790 letter to Adams, Rush said, "My own is the shortest--and perfectly true."

![]() John Morton: A plain farmer, but from his former station as a Judge, was well acquainted with the principles of government, and public business. His hatred to the new Constitution of Pennsylvania, and his anticipation of its evils were such, as to bring on a political hypochondriasis which it was said put an end to his life a year or two after the declaration of independence.

John Morton: A plain farmer, but from his former station as a Judge, was well acquainted with the principles of government, and public business. His hatred to the new Constitution of Pennsylvania, and his anticipation of its evils were such, as to bring on a political hypochondriasis which it was said put an end to his life a year or two after the declaration of independence.

George Clymer: A cool, firm, consistent republican who loved liberty and government with an equal affection. Under the appearance of manners that were cold and indolent he concealed a mind that was always warm and active towards the interests of his country. He was well informed in history ancient and modern and frequently displayed flashes of wit and humour in conversation. His style in writing was simple, correct and sometimes eloquent. "The mould in which this man's mind was cast (to use the words of Lord Peterborough when speaking of Wm. Law) was seldom used."

George Clymer: A cool, firm, consistent republican who loved liberty and government with an equal affection. Under the appearance of manners that were cold and indolent he concealed a mind that was always warm and active towards the interests of his country. He was well informed in history ancient and modern and frequently displayed flashes of wit and humour in conversation. His style in writing was simple, correct and sometimes eloquent. "The mould in which this man's mind was cast (to use the words of Lord Peterborough when speaking of Wm. Law) was seldom used."

![]() James Smith: A pleasant, facetious lawyer. His speeches in Congress were in general declamatory, but from their humour, frequently entertaining.

James Smith: A pleasant, facetious lawyer. His speeches in Congress were in general declamatory, but from their humour, frequently entertaining.

George Taylor: A respectable country gentleman. Not active in Congress.

George Taylor: A respectable country gentleman. Not active in Congress.

![]() James Wilson: An eminent lawyer and a great and enlightened statesman. He had been education for a clergyman in Scotland, and was a profound and accurate scholar. He spoke often in Congress, and his eloquence was of the most commanding kind. He reasoned, declaimed and persuaded, according to circumstances, with equal effect. His mind while he spoke, was one blaze of light. Not a word ever fell from his lips out of time, or out of place, nor could a word be taken from or added to his speeches without injuring them. He rendered great and essential services to his country in every stage of the Revolution.

James Wilson: An eminent lawyer and a great and enlightened statesman. He had been education for a clergyman in Scotland, and was a profound and accurate scholar. He spoke often in Congress, and his eloquence was of the most commanding kind. He reasoned, declaimed and persuaded, according to circumstances, with equal effect. His mind while he spoke, was one blaze of light. Not a word ever fell from his lips out of time, or out of place, nor could a word be taken from or added to his speeches without injuring them. He rendered great and essential services to his country in every stage of the Revolution.

George Ross: A man of great wit, good humour and considerable eloquence. His manner in speaking was agreeable and commanded attention. He disliked business, and hence he possessed but little influence in Congress.

George Ross: A man of great wit, good humour and considerable eloquence. His manner in speaking was agreeable and commanded attention. He disliked business, and hence he possessed but little influence in Congress.

Caesar Rodney: A plain man of good judgment and agreeable conversation; and sincerely devoted to the welfare of his country.

Caesar Rodney: A plain man of good judgment and agreeable conversation; and sincerely devoted to the welfare of his country.

![]() George Read: A lawyer of gentle manners and considerable talents and knowledge. He was firm, without violence, in all his purposes, and was much respected by all his acquaintances.

George Read: A lawyer of gentle manners and considerable talents and knowledge. He was firm, without violence, in all his purposes, and was much respected by all his acquaintances.

Samuel Chase: This man's life and character was a good deal checkered. He rendered great services to his country, by awakening and directing the public spirit of his native State in the first years of the Revolution. He possessed more learning than knowledge, and more of both than judgment. His person and attitude in speaking were graceful and his elocution commanding, but his speeches were more oratorial than logical.

Samuel Chase: This man's life and character was a good deal checkered. He rendered great services to his country, by awakening and directing the public spirit of his native State in the first years of the Revolution. He possessed more learning than knowledge, and more of both than judgment. His person and attitude in speaking were graceful and his elocution commanding, but his speeches were more oratorial than logical.

![]() William Paca: A good tempered worthy man, with a sound understanding which he was too indolent to exercise; and hence his reputation in public life was less than his talents. He was beloved and respected by all who knew him, and considered at all times as a sincere patriot and honest man.

William Paca: A good tempered worthy man, with a sound understanding which he was too indolent to exercise; and hence his reputation in public life was less than his talents. He was beloved and respected by all who knew him, and considered at all times as a sincere patriot and honest man.

![]() Thomas Stone: An able lawyer, and a friend to universal liberty. He spoke well, but was sometimes mistaken upon plain subjects. I once heard him say, "he had never known a single instance of a negro being contented in slavery."

Thomas Stone: An able lawyer, and a friend to universal liberty. He spoke well, but was sometimes mistaken upon plain subjects. I once heard him say, "he had never known a single instance of a negro being contented in slavery."

![]() Charles Carroll: An inflexible patriot, and an honest, independent friend to his country. He had been educated at St. Omer's, and professed considerable learning. He seldom spoke, but his speeches were sensible and correct, and delivered in an oratorial manner.

Charles Carroll: An inflexible patriot, and an honest, independent friend to his country. He had been educated at St. Omer's, and professed considerable learning. He seldom spoke, but his speeches were sensible and correct, and delivered in an oratorial manner.

![]() George Wythe: A profound lawyer, and able politician. He seldom spoke in Congress, but when he did, his speeches were sensible, correct and pertinent. I have seldom known a man possess more modesty, or a more dovelike simplicity and gentleness of manner. He lived many years after he left Congress, the pride and ornament of his native State.

George Wythe: A profound lawyer, and able politician. He seldom spoke in Congress, but when he did, his speeches were sensible, correct and pertinent. I have seldom known a man possess more modesty, or a more dovelike simplicity and gentleness of manner. He lived many years after he left Congress, the pride and ornament of his native State.

![]() Richard Henry Lee: A frequent, correct and pleasing speaker. He was very useful upon committees, and active in expediting business. He made the motion for the declaration of independence, and was ever afterwards one of its most zealous supporters.

Richard Henry Lee: A frequent, correct and pleasing speaker. He was very useful upon committees, and active in expediting business. He made the motion for the declaration of independence, and was ever afterwards one of its most zealous supporters.

Thomas Jefferson: He possessed a genius of the first order. It was universal in its objects. He was not less distinguished for his political, than his mathematical and philosophical knowledge. The objects of his benevolence were as extensive as those of his knowledge. He was not only the friend of his country, but of all nations and religions. While Congress were deliberating upon the measure of sending commissioners to France, I asked him, "What he thought of being one of them." He said, "he would go to hell to serve his country." He was afterwards elected a commissioner, but declined it at that time on account of the sickness of his wife. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was a member of all the important committees. He was the penman of the declaration of independence. He once showed me the original in his own handwriting. It contained a noble testimony against negro slavery which was struck out in its passage through Congress. He took notes of all the debates upon the declaration of independence and the first confederation.

Thomas Jefferson: He possessed a genius of the first order. It was universal in its objects. He was not less distinguished for his political, than his mathematical and philosophical knowledge. The objects of his benevolence were as extensive as those of his knowledge. He was not only the friend of his country, but of all nations and religions. While Congress were deliberating upon the measure of sending commissioners to France, I asked him, "What he thought of being one of them." He said, "he would go to hell to serve his country." He was afterwards elected a commissioner, but declined it at that time on account of the sickness of his wife. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was a member of all the important committees. He was the penman of the declaration of independence. He once showed me the original in his own handwriting. It contained a noble testimony against negro slavery which was struck out in its passage through Congress. He took notes of all the debates upon the declaration of independence and the first confederation.

![]() Benjamin Harrison: He was well acquainted with the forms of public business. He had strong State prejudices and was very hostile to the leading characters from the New England States. In private life he preferred pleasure and convivial company to business of all kinds. His taste in this respect was discovered in a letter to Genl. Washington, which was intercepted and published in Boston. He was upon the whole a useful member of Congress, sincerely devoted to the welfare of his country.

Benjamin Harrison: He was well acquainted with the forms of public business. He had strong State prejudices and was very hostile to the leading characters from the New England States. In private life he preferred pleasure and convivial company to business of all kinds. His taste in this respect was discovered in a letter to Genl. Washington, which was intercepted and published in Boston. He was upon the whole a useful member of Congress, sincerely devoted to the welfare of his country.

![]() Thomas Nelson, Jr.: A respectable country gentleman, with excellent dispositions both in public and private life. He was educated in England. He informed that he was the only person out of nine or ten Virginians that were sent with him to England for education that had taken a part in the American Revolution. The rest were all Tories.

Thomas Nelson, Jr.: A respectable country gentleman, with excellent dispositions both in public and private life. He was educated in England. He informed that he was the only person out of nine or ten Virginians that were sent with him to England for education that had taken a part in the American Revolution. The rest were all Tories.

![]() Francis Lightfoot Lee: He was brother to Richard Henry Lee, but possessed I thought a more acute and correct mind. He often opposed his brother in a vote, but never spoke in Congress. I seldom knew him wrong eventually upon any question. Mr. Madison informed me that he had observed the same thing in many silent members of public bodies.

Francis Lightfoot Lee: He was brother to Richard Henry Lee, but possessed I thought a more acute and correct mind. He often opposed his brother in a vote, but never spoke in Congress. I seldom knew him wrong eventually upon any question. Mr. Madison informed me that he had observed the same thing in many silent members of public bodies.

![]() Carter Braxton: He was not deficient in political information, but was suspected of being less detached than he should be from his British prejudices. He was an agreeable and sensible speaker, and in private life an accomplished gentleman.

Carter Braxton: He was not deficient in political information, but was suspected of being less detached than he should be from his British prejudices. He was an agreeable and sensible speaker, and in private life an accomplished gentleman.

![]() Joseph Hewes: A plain, worthy merchant, and well acquainted with business. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was very useful upon committees.

Joseph Hewes: A plain, worthy merchant, and well acquainted with business. He seldom spoke in Congress, but was very useful upon committees.

![]() William Hooper: A sensible sprightly young lawyer and a rapid but correct speaker.

William Hooper: A sensible sprightly young lawyer and a rapid but correct speaker.

![]() John Penn: A good humoured man, very talkative in company, but seldom spoke in Congress. He was honest, and warmly attached to the liberties of his country.

John Penn: A good humoured man, very talkative in company, but seldom spoke in Congress. He was honest, and warmly attached to the liberties of his country.

Edward Rutledge: A sensible young lawyer, of great volubility in speaking, and very useful in the business of Congress.

Edward Rutledge: A sensible young lawyer, of great volubility in speaking, and very useful in the business of Congress.

![]() Thomas Heyward, Jr.: A firm republican of good education and most amiable manners. He possessed an elegant poetical genius, which he sometimes exercised with success upon the various events of the war.

Thomas Heyward, Jr.: A firm republican of good education and most amiable manners. He possessed an elegant poetical genius, which he sometimes exercised with success upon the various events of the war.

![]() Thomas Lynch, Jr.: A man of moderate talents, and not bold in difficult circumstances of his country.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.: A man of moderate talents, and not bold in difficult circumstances of his country.

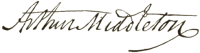

Arthur Middleton: A man of cynical temper, but of upright intentions towards his country. He had been educated in England and was a critical Latin and Greek scholar. He read Horace and other classics during his recess from Congress. He spoke frequently, and always with asperity or personalities. He disliked business, and when put upon the committee of accounts he refused to serve, and gave as a reason for it that, "he hated accounts--that he did not even keep his own accounts, and that he knew nothing about them."

Arthur Middleton: A man of cynical temper, but of upright intentions towards his country. He had been educated in England and was a critical Latin and Greek scholar. He read Horace and other classics during his recess from Congress. He spoke frequently, and always with asperity or personalities. He disliked business, and when put upon the committee of accounts he refused to serve, and gave as a reason for it that, "he hated accounts--that he did not even keep his own accounts, and that he knew nothing about them."

![]() Button Gwinnett: A zealous democrat. He carried a copy of the first constitution of Pennsylvania with him to Georgia, where he had address enough to get it adopted. He fell soon afterwards in a duel in that State.

Button Gwinnett: A zealous democrat. He carried a copy of the first constitution of Pennsylvania with him to Georgia, where he had address enough to get it adopted. He fell soon afterwards in a duel in that State.

![]() Lyman Hall: A native of Connecticut, and strongly impressed with the principles and habits of republicanism which then prevailed in that State. He was a man of considerable learning, with an excellent judgment and very amiable manners.

Lyman Hall: A native of Connecticut, and strongly impressed with the principles and habits of republicanism which then prevailed in that State. He was a man of considerable learning, with an excellent judgment and very amiable manners.

![]() George Walton: A sensible young man. He possessed knowledge and a pleasing manner of speaking. he was the youngest member of Congress being not quite three and twenty when he signed the declaration of independence. He filled the offices of Governor and Chief Justice for many years in Georgia, and evinces in his public conduct the same attachment to government and order that he had done in 1776 to liberty and independence.

George Walton: A sensible young man. He possessed knowledge and a pleasing manner of speaking. he was the youngest member of Congress being not quite three and twenty when he signed the declaration of independence. He filled the offices of Governor and Chief Justice for many years in Georgia, and evinces in his public conduct the same attachment to government and order that he had done in 1776 to liberty and independence.

The one delegate missing from Rush's list is Thomas McKean. As we have shown, McKean signed the Declaration of Independence sometime after January 1777 and possibly as late as 1781, and as a result, his name was left off of a number of printings of the signatories of the Declaration. Rush was likely working from one of these printings, since his list of characters roughly follows the same signing order and state order as the engrossed parchment.

In a letter to Adams written January 26, 1813, Rush said, "Of the members of Congress who subscribed the declaration of Independance nine only are now living. J Langdon of New Hampshire--Paine, Gerry & yourself in Massachusetts--Floyd in New York--Rush in Pennsylvania--McKean of Delaware--Johnson of Maryland, and Jefferson of Virginia. All of them are above 70 except Mr Gerry and myself." Rush included McKean as a signer of the Declaration, but he also included John Langdon and Thomas Johnson, who were not signers (Langdon signed the Constitution, and Johnson left the Continental Congress before the Declaration was signed). As we said, take Rush with a grain of salt.

Even if Rush's descriptions aren't completely historically accurate, he succeeded in providing posterity with a glimpse into the personalities of the Founding Fathers. He correctly predicted that we would have a fuzzy view of these individuals, influenced by popularity and pop culture. We envision the men depicted in Trumbull's painting, or (perhaps even worse) in 1776. The musical even includes Adam's "smote" quote from his correspondence with Rush, though transplanted into a conversation with Benjamin Franklin for a much more amusing moment:

Franklin: "Don't worry, John, the history books will clean it up."

Adams: "Hmm... Well, I'll never appear in the history books anyway. Only you. Franklin did this, and Franklin did that, and Franklin did some other damn thing. Franklin smote the ground and out sprang George Washington -- fully grown and on his horse. Franklin then electrified him with his miraculous lightning rod and the three of them, Franklin, Washington and the horse, conducted the entire revolution all by themselves."

Franklin: "... I like it."

Note: The quote in the second paragraph is pulled from Travels through Life, and not from Rush's personal correspondence.

By Emily Sneff