In First Family: Abigail and John Adams, Joseph Ellis claims, “there were other prominent couples in the revolutionary era... But no other couple left a documentary record of their mutual thoughts and feelings even remotely comparable to Abigail and John’s.” The correspondence of Abigail and John Adams is fascinating and detailed, particularly during the two years when John was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. John writes candid impressions of major events, including the vote for independence, to his wife. Abigail in turn reports on not just the health and wellbeing of their children, but on major events in the Boston area, including the Battle of Bunker Hill and Boston’s first reading of the Declaration of Independence.

In First Family: Abigail and John Adams, Joseph Ellis claims, “there were other prominent couples in the revolutionary era... But no other couple left a documentary record of their mutual thoughts and feelings even remotely comparable to Abigail and John’s.” The correspondence of Abigail and John Adams is fascinating and detailed, particularly during the two years when John was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. John writes candid impressions of major events, including the vote for independence, to his wife. Abigail in turn reports on not just the health and wellbeing of their children, but on major events in the Boston area, including the Battle of Bunker Hill and Boston’s first reading of the Declaration of Independence.

From late April 1775 through November 1777, Abigail and John spent upwards of 27 months apart, and their extensive correspondence is preserved at the Massachusetts Historical Society. In previous blog posts, we have highlighted letters between John and Abigail from 1776 – “Remember the Ladies...” “Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light...” and others. For this month’s Research Highlight, we asked the editors of the Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society to share a few significant letters between John and Abigail Adams from 1775 and 1777. Hobson Woodward, Series Editor of the Adams Family Correspondence at the Adams Papers, picked the following four letters and shared the details that make these letters stand out among this couple’s vast correspondence.

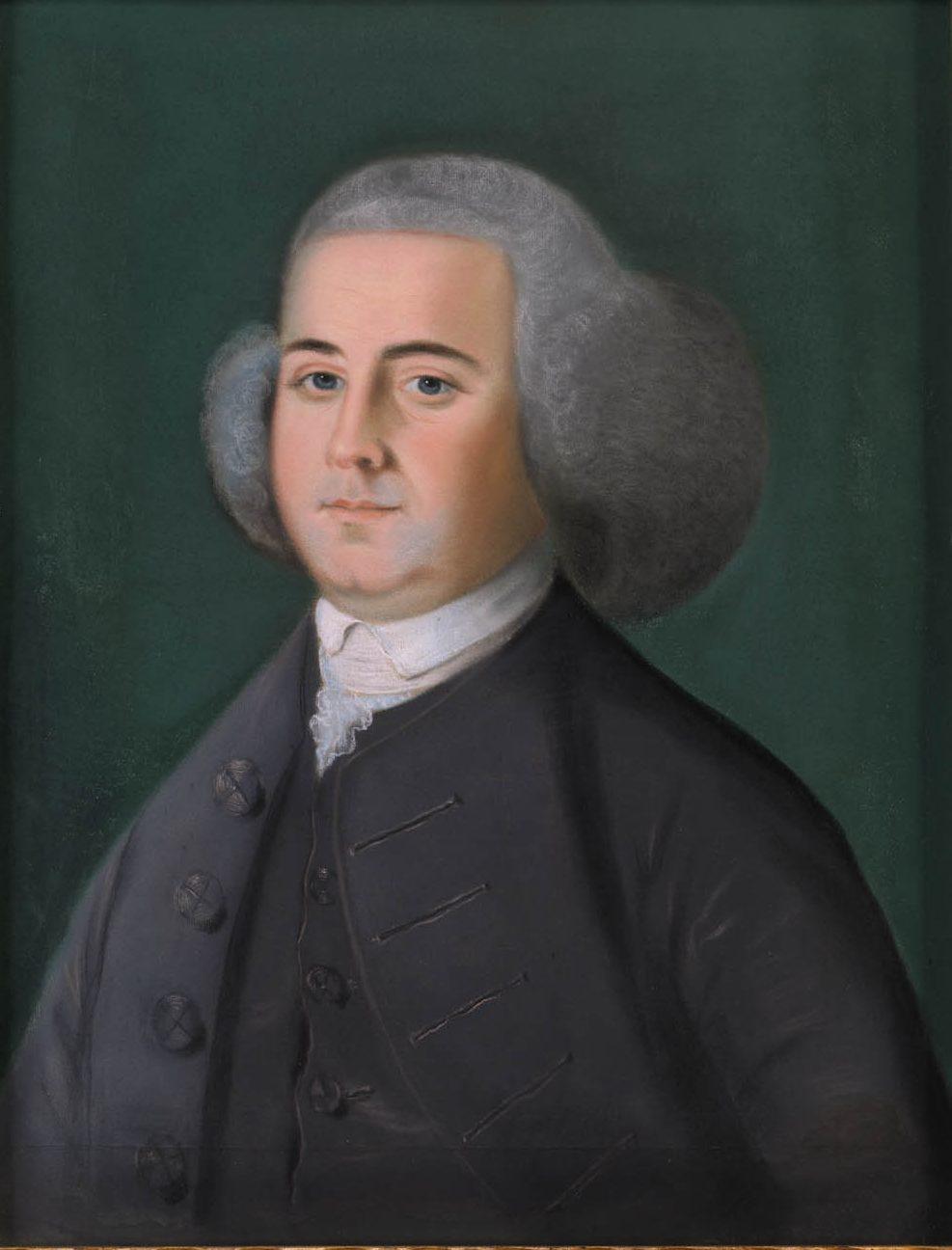

Portraits of Abigail and John Adams by Benjamin Blyth, 1766

John turned 39 years old in October 1774, and Abigail turned 30 in November. As of October 1774, they had been married for 10 years and had four living children: Abigail (“Nabby,” b. 1765), John Quincy (b. 1767), Charles (b. 1770), and Thomas Boylston (b. 1772). A daughter, Grace Susanna, died in 1770, and another daughter, Elizabeth, was stillborn in 1777. The Adams family lived in Braintree, on a plot of farmland John inherited from his father. The home they lived in during this period is recognized today as the John Quincy Adams Birthplace.

John Adams set out for Philadelphia around April 26, 1775, just a week after Lexington and Concord. The Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, and John remained in Philadelphia until December 8, 1775. After spending the winter in Massachusetts, John left for Philadelphia again on January 24, 1776 and attended Congress regularly from February 9-October 12, at which point he obtained leave to return to Massachusetts. He travelled from Braintree to Baltimore, the new meeting place for the Congress, in January and early February 1777, and remained with the Congress until November 10, at which point he returned home once again. He would not return to the Continental Congress, because on November 27, 1777, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Arthur Lee were commissioned as diplomats to France, with Adams replacing Silas Deane.

1775

Hobson Woodward, Series Editor of the Adams Family Correspondence, selected two letters from 1775. The first was written as John Adams departed for Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress. In the second, Abigail Adams shared the news of their friend’s death at Bunker Hill.

Letter from John to Abigail, 30 April 1775

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

“When he looked back on the American Revolution many years later in his autobiography, John Adams declared that the Battles of Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775 ‘changed the Instruments of Warfare from the Penn to the Sword.’ A few days after the events of that day he departed Braintree and rode out to survey the battlefields. ‘I rode from thence to Lexington and along the Scene of Action for many miles and enquired of the Inhabitants, the Circumstances. These were not calculated to diminish my Ardour in the Cause. They on the Contrary convinced me that the Die was cast, the Rubicon passed, and . . . if We did not defend ourselves they would kill Us.’

A somber Adams returned to Braintree, Mass., and prepared to leave his young family and travel to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress. Beset by fever, he went by carriage rather than horseback. The first letter he wrote home to Abigail was written from Hartford, Connecticut, and dated 30 April. In the short note John assured Abigail that he was being treated well by all whom he met. He communicated political developments, but the essence of the letter was his reassuring words to his wife:

Keep your Spirits composed and calm, and dont suffer your self to be disturbed, by idle Reports, and frivolous Alarms. We shall see better Times yet.

John’s confidence in the eventual outcome of the Revolution was not always so firm. Consider his words to Abigail a few days later: ‘In Case of real Danger, of which you cannot fail to have previous Intimations, fly to the Woods with our Children.’ On 30 April, however, a departing husband told a nervous wife that all would be well despite open warfare a few miles from their home.”

Letter from Abigail to John, 18 June 1775

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

“Two months after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, the conflict shifted to full-scale war at the Battle of Bunker Hill. On 17 June 1775, Abigail and her eight-year-old son John Quincy watched from the top of Penn’s Hill in Braintree as the battle raged in Charlestown. Seventy years later, John Quincy recalled the scene in a letter to a friend: ‘I saw with my own eyes those fires, and heard Britannia's thunders in the Battle of Bunker's hill and witnessed the tears of my mother and mingled with them my own, at the fall of Warren a dear friend of my father, and a beloved Physician to me.’

The death of family friend Dr. Joseph Warren was a grievous blow to Abigail and John. The day after the battle Abigail wrote a letter to John in Philadelphia, reporting the loss and describing events to the north:

The Day; perhaps the decisive Day is come on which the fate of America depends. My bursting Heart must find vent at my pen. I have just heard that our dear Friend Dr. Warren is no more but fell gloriously fighting for his Country—saying better to die honourably in the field than ignominiously hang upon the Gallows. Great is our Loss. He has distinguished himself in every engagement, by his courage and fortitude, by animating the Soldiers and leading them on by his own example.

Charlstown is laid in ashes. The Battle began upon our intrenchments upon Bunkers Hill, a Saturday morning about 3 o clock and has not ceased yet and tis now 3 o'clock Sabbeth afternoon. Tis expected they will come out over the Neck to night, and a dreadful Battle must ensue. Almighty God cover the heads of our Country men, and be a shield to our Dear Friends. How [many ha]ve fallen we know not—the constant roar of the cannon is so [distre]ssing that we can not Eat, Drink or Sleep. May we be supported and sustaind in the dreadful conflict.

Gathered around Abigail were her children, Abigail 2d, 10; John Quincy, 8; Charles, 5; and Thomas, 2. Her husband was a leader of the rebellion that had now flashed into pitched battle. This was ‘perhaps the decisive Day’ for America, but it was also a decisive day for the future of her family.”

1776

As noted above, we have highlighted letters between John and Abigail from 1776 in previous posts. Click the hyperlink following each quote for the relevant posts in our blog archive.

Letter from John to Abigail, February 18, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

Reconciliation if practicable and Peace if attainable, you very well know would be as agreable to my Inclinations and as advantageous to my Interest, as to any Man’s. But I see no Prospect, no Probability, no Possibility. And I cannot but despise the Understanding, which sincerely expects an honourable Peace, for its Credulity, and detest the hypocritical Heart, which pretends to expect it, when in Truth it does not.

Phrases from this paragraph were incorporated into the dialogue in the John Adams miniseries: “But, I see no prospect for it, no probability, no possibility! And I cannot abide the hypocritical heart that pretends to expect peace when in truth it does not.” Read more

Letter from Abigail to John, March 2, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

Letter from John to Abigail, March 19, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

John enclosed a copy of Common Sense in his letter to Abigail of February 18, and she replied:

I am charmed with the Sentiments of Common Sense; and wonder how an honest Heart, one who wishes the welfare of their country, and the happiness of posterity can hesitate one moment at adopting them; I want to know how those Sentiments are received in Congress? I dare say their would be no difficulty in procuring a vote and instructions from all the Assemblies in New England for independancy.

John answered her query on March 19, explaining the failings of the pamphlet, and that it had been attributed to him: “altho I could not have written any Thing in so manly and striking a style, I flatter myself I should have made a more respectable Figure as an Architect, if I had undertaken such a Work.” Read more

Letter from Abigail to John, March 31, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

Letter from Abigail to John, May 7, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

In March 1776, anticipating independence, Abigail famously asked her husband to “Remember the Ladies...”

I long to hear that you have declared an independency -- and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

John’s response on April 14 – “I cannot but laugh... Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems” – was clearly unsatisfactory. Abigail fired back on May 7: “I can not say that I think you very generous to the Ladies, for whilst your are proclaiming peace and good will to Men, Emancipating all Nations, you insist upon retaining an absolute power over Wives.” But even in this volley of letters about women’s rights, John and Abigail expressed their love and appreciation for each other, with Abigail calling John “the Friend of my heart.” Read more

Letter from John to Abigail, July 3, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

In one of two letters written to Abigail the day after independence was declared, John predicted that July 2nd would be “the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America... solemnized with Pomp and Parade...” Both this passage and the following paragraph were incorporated into the lyrics for “Is Anybody There?” in the musical 1776.

You will think my transported with Enthusiasm but I am not.—I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure, that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States.—Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory. I can see that the End is more than worth all the Means. And that Posterity will tryumph in that Days Transaction, even altho We should rue it, which I trust in God We shall not. Read more

Letter from Abigail to John, July 21, 1776

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

John was witness to the first documented public reading of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia on July 8, and on July 18, Abigail witnessed the first public reading in Boston. She recounted the days’ events as follows:

Last Thursday after hearing a very Good Sermon I went with the Multitude into Kings Street to hear the proclamation for independance read and proclamed. Some Field peiceswith the Train were brought there, the troops appeard under Arms and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small pox prevented many thousand from the Country). When Col.Crafts read from the Belcona of the State House the Proclamation, great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the Belcona, was God Save our American States and then 3 cheers which rended the air, the Bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and Batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed and every face appeard joyfull.Mr. Bowdoin then gave a Sentiment, Stability and perpetuity to American independence. After dinner the kings arms were taken down from the State House and every vestage of him from every place in which it appeard and burnt in King Street. Thus ends royall Authority in this State, and all the people shall say Amen. Read more

1777

For 1777, Hobson Woodward again selected one letter written by Abigail Adams, and one written by John. In the first, a pregnant Abigail reflected on the hardship and separation required of them. The second found John earnestly wishing to return to his farm and his family.

Letter from Abigail to John, 8 March 1777

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

“After John again left Braintree to attend Congress in Philadelphia in the spring of 1777, Abigail was in a more philosophical mood in her letters to him. On 8 March 1777 she took a longer view of the efforts of their generation:

Posterity who are to reap the Blessings, will scarcly be able to conceive the Hardships and Sufferings of their Ancesstors.

John and Abigail often wrote of missing each other. Their correspondence offers a revealing view of a couple in a time of crisis. The 8 March letter includes passages from Abigail to her husband in which she left as much unsaid as said:

Rejoice with you in your agreable situation, tho I cannot help wishing you nearer. Shall I tell you how near?

You make some inquiries which tenderly affect me. I think upon the whole I have enjoyed as much Health as I ever did in the like situation—a situation I do not repine at, tis a constant remembrancer of an absent Friend, and excites sensations of tenderness which are better felt than expressd.

Abigail reported that their children were well, and that young Thomas had a request. ‘Master T. desires I would write a Letter for him which I have promissed to do.’ Life went on in time of war, as the letters of the Adamses reveal again and again.”

Letter from John to Abigail, 16 March 1777

Read this letter in the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive

“John in March 1777 was also ruminating on the future of his family and country. His letters mixed thoughts of the emerging nation’s welfare with tender messages to his wife. Though he longed for American independence, he also wished for a peaceful life with Abigail on their farm. At heart he was a Braintree yeoman:

What Pleasures has not this vile War deprived me of? I want to wander, in my Meadows, to ramble over my Mountains, and to sit in Solitude, or with her who has all my Heart, by the side of the Brooks. These beautifull Scaenes would contribute more to my Happiness, than the sublime ones which surround me. I begin to suspect that I have not much of the Grand in my Composition. The Pride and Pomp of War, the continual Sound of Drums and Fifes as well played, as any in the World, the Prancings and Tramplings of the Light Horse numbers of whom are paraded in the Streets every day, have no Charms for me. I long for rural and domestic scaenes, for the warbling of Birds and the Prattle of my Children.— Dont you think I am somewhat poetical this morning, for one of my Years, and considering the Gravity, and Insipidity of my Employment.— As much as I converse with Sages and Heroes, they have very little of my Love or Admiration. I should prefer the Delights of a Garden to the Dominion of a World. I have nothing of Caesars Greatness in my soul. Power has not my Wishes in her Train. The Gods, by granting me Health, and Peace and Competence, the Society of my Family and Friends, the Perusal of my Books, and the Enjoyment of my Farm and Garden, would make me as happy as my Nature and State will bear.

More than two decades later he would get his wish, though under less desirable circumstances. The correspondence between John and Abigail came to an end in 1800 after Thomas Jefferson defeated John’s bid for reelection to the U.S. presidency. John and Abigail were reunited for their remaining eighteen years together. They wrote widely to family and friends, but never again to each other, as they were continually together on the farm John called Peacefield. A painful election defeat brought John Adams the serenity he longed for in 1777. He was now free ‘to wander, in my Meadows, to ramble over my Mountains, and to sit in Solitude, or with her who has all my Heart, by the side of the Brooks.’”

We thank the Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society and especially Hobson Woodward for contributing to this blog post. Visit the Adams Family Papers Electronic Archive for transcriptions and images of the correspondence between Abigail and John Adams. The Electronic Archive has over 300 letters from 1775-1777, so the ones included in this post are truly just the tip of the iceberg!

By Emily Sneff