Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was presented on June 7, 1776, it called for these three things, in this order:

Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was presented on June 7, 1776, it called for these three things, in this order:

- That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be totally dissolved.

- That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

- That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

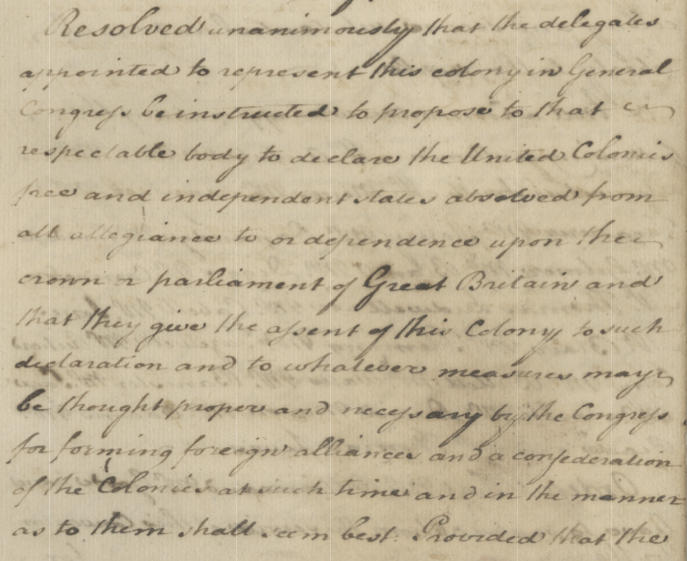

His resolution, or more accurately, his three resolutions were adapted from those of the Virginia Convention, agreed to on May 15: “Resolved, unanimously, That the Delegates appointed to represent this Colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain; and that they give the assent of this Colony to such declaration, and to whatever measures may be thought proper and necessary by the Congress for forming alliances, and a Confederation of the Colonies, at such time and in the manner as to them shall seem best: Provided, That the power of forming Governments for, and the regulations of the internal concerns of each Colony, be left to the respective Colonial Legislatures.”

Minutes of the Virginia Convention, Library of Virginia

The Journals of the Continental Congress show that these three resolutions occupied the debate on Saturday, June 8 and Monday, June 10. John Hancock even let George Washington know, “we have been two Days in a Committee of the Whole deliberating on three Capital Matters, the most important in their Nature of any that have yet been before us…” On the 10th, Congress resolved, “that the consideration of the first resolution be postponed to this day, three weeks, and in the mean while, that no time be lost, in case the Congress agrees thereto, that a committee be appointed to prepare a declaration to the effect of the said first resolution.” This pushed the discussion of independence to July 1.

On June 11, a committee of five men – Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston – was chosen to draft a declaration. That same day, Congress resolved, “That a committee be appointed to prepare and digest the form of a confederation to be entered into between these colonies,” and, “That a committee be appointed to prepare a plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers.” Even though, on the 10th, Congress was focused on the first resolution concerning independence, the resolutions concerning confederation and foreign alliances were still at the forefront of their collective thought. On June 12, a committee with one member from each colony (except for New Jersey) was appointed to prepare a plan for confederation, and another committee of five men was appointed to prepare a plan for treaties. As might be expected, there is some overlap between these three crucial committees.

| Declaration Committee | Confederation Committee | Treaties Committee |

|---|---|---|

| John Adams | Samuel Adams (MA) | John Adams |

| Benjamin Franklin | Josiah Bartlett (NH) | John Dickinson |

| Thomas Jefferson | John Dickinson (PA) | Benjamin Franklin |

| Robert R. Livingston | Button Gwinnett (GA) | Benjamin Harrison |

| Roger Sherman | Joseph Hewes (NC) | Robert Morris |

| Stephen Hopkins (RI) | ||

| Robert R. Livingston (NY) | ||

| Thomas McKean (DE) | ||

| Thomas Nelson, Jr. (VA) | ||

| Edward Rutledge (SC) | ||

| Roger Sherman (CT) | ||

| Thomas Stone (MD) |

Just over two weeks later, on June 28, the committee appointed to prepare a declaration presented their draft to Congress, two days before the planned resumption of debate on July 1. The rest is history: Congress voted in favor of independence on July 2, and approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4. It is unclear whether the other two committees were expected to present their drafts on July 1, or at a different time. On June 29, Edward Rutledge nearly begged John Jay to come to Congress, saying, “I know full well that your Presence must be useful at New York, but I am sincerely convinced that it will be absolutely necessary in this City during the whole of the ensuing week. A Declaration of Independence, the Form of a Confederation of these Colonies, and a Scheme for a Treaty with foreign Powers will be laid before the House on Monday.” On July 1, Josiah Bartlett wrote to Nathaniel Folsom, “The whole Congress are unanimous for forming a plan of Confederation of the Colonies,” and indicated that their draft was nearly ready. On July 3, John Adams informed his wife, Abigail, “A Plan of Confederation will be taken up in a few days.”

The committee appointed to prepare a plan for confederation presented their draft to Congress on July 12, and the committee appointed to prepare a plan for treaties presented a report to Congress on July 18. But, in the end, the plan for treaties to be proposed to foreign powers wasn’t agreed upon until September, and the Articles of Confederation weren’t agreed upon and sent to the states for ratification until November 1777, more than seventeen months after the committee to prepare them was originally appointed. How did these three elements, so closely tied together in months of discussion and debate before July 1776, become so separated?

One significant difference between a declaration of independence, articles of confederation, and a plan for treaties with foreign powers, is that Congress intended for any plan for confederation to be approved by the colonies/states. Given the pace of mail in the American colonies, the war, the fact that many colonies were in the process of drafting their own constitutions, and myriad other factors, it would have been impossible to draft, debate, distribute, and enact the Articles of Confederation in a timely manner.

On February 13, 1776, Thomas Nelson, Jr. wrote, “Independence, Confederation & foreign alliance are as formidable to some of the Congress, I fear to a majority, as an apparition to a weak enervated Woman.” But, over time, even the most ardent supporters of reconciliation began to realize that other preparations were necessary. On May 20, John Adams wrote to James Warren of his main political opponent, John Dickinson, “What do you think must be my Reflections when I see, the Farmer himself, now confessing the Falsehood of all his Prophecies, and the Truth of mine, and confessing himself, now for instituting Governments, forming a Continental Constitution, making Alliances, with foreigners, opening Ports and all that…?” By June, it seems that there was a general consensus that the Continental Congress needed to plan for independence, confederation and foreign alliances. But, in what order? Letters between delegates and accounts of debates in Congress show that opinions were varied and often obstinate, and even after independence was declared, members of Congress had regrets about the order of events.

Confederation and Foreign Alliances, then Independence

On June 8, Edward Rutledge recounted the events in Congress to John Jay: “The Sensible part of the House opposed the Motion [of Lee’s resolution]. They had no Objection to forming a Scheme of a Treaty which they would send to France by proper Persons, & a uniting this Continent by a Confederacy. They saw no Wisdom in a Declaration of Independence, nor any other Purpose to be answer’d by it, but placing ourselves in the Power of those with whom we mean to treat, giving our Enemy Notice of our Intentions before we had taken any Steps to execute them & there by enabling them to counteract us in our Intentions & rendering ourselves ridiculous in the Eyes of foreign Powers by attempting to bring them into an Union with us before we had united with each other.” Rutledge presented a clear order: confederation, then treaties, then maybe independence (the reverse is what actually ended up happening).

John Dickinson drafted the Articles of Confederation and argued in favor of reconciliation, or at the very least, agreeing on plans for confederation and treaties before declaring independence. In the notes he likely prepared for his speech in Congress on July 1, John Dickinson answered the potential critique, that “the People expect it,” by saying, “Let them know it is only deferred till a Confederation or a Treaty with Foreign Powers is concluded.” Dickinson abstained from voting on both July 2 and July 4, left Congress to serve in the Pennsylvania militia, and did not sign the Declaration of Independence. Ironically, it took so long for the Articles of Confederation to be ratified, that Dickinson was able to sign that document during his second appointment to Congress, as a delegate from Delaware.

On July 28, North Carolina delegate Joseph Hewes grumbled, “Much of our time is taken up in forming and debating a Confederation for the united States, what we shall make of it God only knows, I am inclined to think we shall never modell it so as to be agreed to by all the Colonies.” He continued, “A plan for foreign Alliances is also formed and I expect will be the subject of much debate before it is agreed to. These two Capital points ought to have been setled before our declaration of Independance went forth to the world, this was my opinion long ago and every days experience serves to confirm me in that opinion.”

Confederation, then Foreign Alliances

Was a confederation of the colonies/states necessary to secure foreign alliances? Certain delegates thought so. On May 11, William Whipple wrote to Meshech Weare, “A Confederation of the Colonies is absolutely necessary to enable Congress to Conclude foreign alliances.” A week later, Whipple wrote to John Langdon, “A confederation permanent and lasting, ought in my opinion to be the next thing and I hope is not far off: if so then the establishment of foreign Agencies I hope will fill our ports with ships from all parts of the world.”

On May 12, John Adams wrote to John Winthrop, “The Question of Independence is so vast a Field that I have not Time to enter it, and go any Way in it. Many previous steps are necessary. The Colonies should all assume the Powers of Government in all its Branches first. They should confederate with each other, and define the Powers of Congress next. They should then, endeavour to form an Alliance with some foreign State. When this is done, a public Declaration might be made.” He added, “Such a Declaration may be necessary, in order to obtain a foreign Alliance—and it should be made for that End.” But, on May 17, Adams wrote to his wife, “Confederation among ourselves, or Alliances with foreign Nations are not necessary, to a perfect Seperation from Britain. That is effected by extinguishing all Authority, under the Crown, Parliament and Nation as the Resolution for instituting Governments, has done, to all Intents and Purposes. Confederation will be necessary for our internal Concord, and Alliances may be so for our external Defence.”

On July 30, Samuel Chase wrote to Richard Henry Lee, “I hurried to Congress to give my little assistance to the framing a Confederacy and a plan for a foreign alliance, both of them Subjects of the utmost Importance, and which in my Judgment demand immediate Dispatch.” He lamented, “We shall remain weak, and distracted and divided in our Councils, our Strength will decrease, we shall be open to all the arts of the insidious Court of Britain, and no foreign Court will attend to our applications for Assistance before We are confederated. What Contract will a foreign State make with Us, when We cannot agree among Ourselves?”

Independence, then Confederation and Foreign Alliances

On June 2, Richard Henry Lee wrote to fellow Virginian Landon Carter, “It is not choice then, but necessity that calls for Independence, as the only means by which foreign Alliance can be obtained; and a proper confederation by which internal peace and union may be secured…” In a letter written after July 4th, Samuel Adams noted, “it must be allowd by the impartial World that this Declaration has not been made rashly,” and added, “our path is now open to form a plan of Confederation & propose Alliances with foreign States. I hope our Affairs will now wear a more agreable Aspect than they have of late.”

Order Doesn’t Matter, But Time Does!

The Massachusetts delegates had been ready for independence and all that it entailed for months. On June 11, Elbridge Gerry wrote, “If these slow people had hearkened to reason in time, this work would have long ere now been completed, and the disadvantage arising from the want of such measures been wholly avoided; but Providence has undoubtedly wise ends in coupling together the vigorous and the indolent; the first are retarded, but the latter are urged on, and both come together to the goal.”

On July 15, Samuel Adams sent an update to Richard Henry Lee, who had left Congress in mid-June: “A Plan of Confederation has been brot into Congress wch I hope will be speedily digested and made ready to be laid before the several States for their Approbation. A Committee has now under Consideration the Business of foreign Alliance. It is high time for us to have Ambassadors in foreign Courts. I fear we have already sufferd too much by Delay.”

On June 6, knowing that Richard Henry Lee would be presenting his resolution the next day, Samuel Adams wrote, “This will, in my opinion, be an important Summer, productive of great Events which we must be prepard to meet. If America is virtuous, she will vanquish her Enemies and establish her Liberty.” Even if the pieces of the Lee Resolution were addressed in a different order and at a slower pace than many delegates anticipated or preferred, Adams was right – the summer of 1776 was a productive one.

Emily Sneff

Last | Delegate Discussions