On July 11th, 1776, John Quincy Adams turned 9 years old. On July 12th, he was inoculated for smallpox along with his mother Abigail and his siblings. And on July 13th, Abigail received her husband John’s letters with news of the Declaration of Independence. From this young age through his death in 1848, John Quincy Adams was deeply tied to the Declaration of Independence. He wasn’t just the son of John Adams, a member of the committee tasked with drafting the document and a signer. He was also a politician clearly inspired by the Declaration, and frequently tasked with discussing its importance. In this month’s Research Highlight, we belatedly celebrate John Quincy Adams’ 250th birthday with a look at the many connections between this Adams and the Declaration.

On July 11th, 1776, John Quincy Adams turned 9 years old. On July 12th, he was inoculated for smallpox along with his mother Abigail and his siblings. And on July 13th, Abigail received her husband John’s letters with news of the Declaration of Independence. From this young age through his death in 1848, John Quincy Adams was deeply tied to the Declaration of Independence. He wasn’t just the son of John Adams, a member of the committee tasked with drafting the document and a signer. He was also a politician clearly inspired by the Declaration, and frequently tasked with discussing its importance. In this month’s Research Highlight, we belatedly celebrate John Quincy Adams’ 250th birthday with a look at the many connections between this Adams and the Declaration.

As Secretary of State

1817-1825

The fact that large-scale, decorative copies and “facsimiles” of the Declaration of Independence became popular during John Quincy Adams’ time as Secretary of State is no coincidence. First off, as the country recovered from the War of 1812 and recognized that members of the founding generation were fading away, interest in the Declaration surged. Second, the Secretary of State himself was invested in ensuring that the engrossed and signed parchment in his custody lasted in spite of its already-faded appearance.

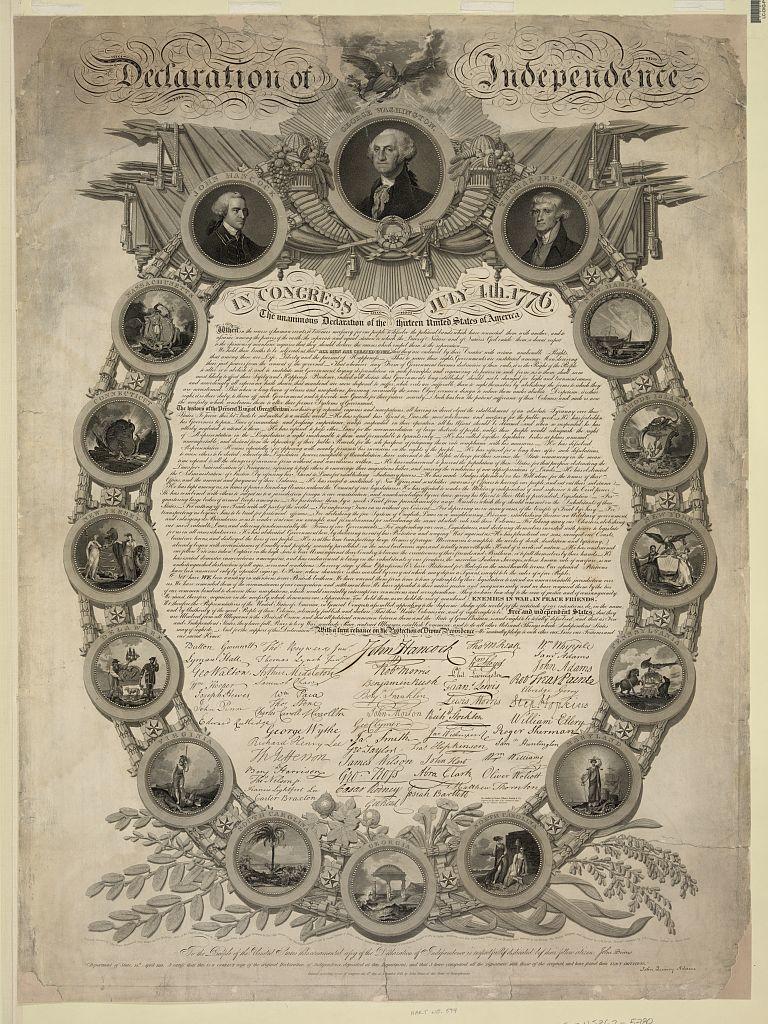

In 1819, John Binns printed his copy of the Declaration, with the text and facsimile signatures set in a decorative oval frame. A note at the bottom of Binns’ engraving reads, “Department of State, 19th. April 1819. I certify, that this is a CORRECT copy of the original Declaration of Independence, deposited at this Department; and that I have compared all the signatures with those of the original, and have found them EXACT IMITATIONS.” The note bears John Quincy Adams’ signature.

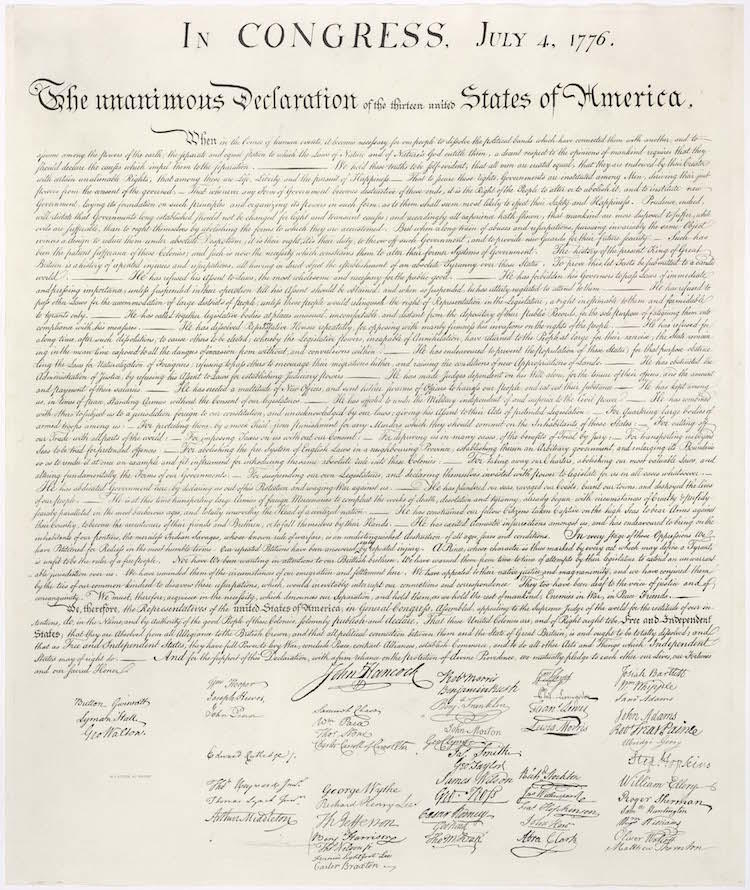

L: 1819 engraving by John Binns; R: 1823 engraving by William J. Stone

Another engraving of the Declaration of Independence wasn’t just certified by Adams, but was ordered by him. In 1820, Secretary Adams received Congressional approval to commission an exact copy of the engrossed and signed parchment. Adams gave this important assignment to D.C.-based engraver William J. Stone, who set to work creating a copperplate engraving of the Declaration.

According to Adams’ diary, Stone had completed his “fac-simile of the original Declaration of Independence” by April 11, 1823. State Department clerk Daniel Brent wrote to Stone in May to request 200 copies, and to deliver the engraving plate itself to the State Department when he was finished. Stone actually printed 201 copies of his engraving on vellum; the 201st was given to the Smithsonian by his widow. A year later, in May 1824, Congress resolved for Secretary Adams to distribute the Stone engraving. Two copies each were sent to President James Monroe and Vice President Daniel D. Thompkins, along with two to the White House and two to the Supreme Court chamber; twenty copies were split among Congress, and federal departments, governors, state legislatures, and universities also received copies. Two copies each were sent to James Madison, and to the Marquis de Lafayette.

On June 24, 1824, John Quincy Adams sent two copies of the Stone engraving each to the three living signers of the Declaration: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton. Notably, the letters sent to Jefferson and Carroll are nearly identical to the one Adams sent to his father.

“In pursuance of a joint Resolution, of the two Houses of Congress, a copy of which is hereto annexed, and by direction of the President of the United States, I have the honour of transmitting two fac simile copies of the original Declaration of Independence, engrossed on parchment, conformably to a secret Resolution of Congress 19 July 1776, to be signed by every member of Congress, and accordingly signed on the second day of August of the same year.

Of this Document, unparalleled in the Annals of Mankind, the original deposited in this Department exhibits your name as one of the Subscribers. The rolls herewith transmitted are copies as exact as the art of engraving can present of the Instrument itself, as well as of the signatures to it—While performing the duty thus assigned to me, permit me to felicitate you and the Country which is reaping the reward of your labours, as well that your hand was affixed to this record of glory, as that after the lapse of near half a century, you survive to receive this tribute of reverence and gratitude from your children, the present fathers of the Land.

With every Sentiment of Veneration, I have the honour of subscribing myself, your Fellow-Citizen.

John Quincy Adams.”

Each of the 200 copies ordered by Adams bears an imprint, “ENGRAVED by W.I. STONE, for the Dept. of State, by order of J.Q. Adams, Sect. of State, July 4th, 1823.” Although it is not an exact facsimile, and although its method of production is still debated, Stone’s engraving is the image that most often comes to mind when modern Americans think of the Declaration of Independence, and that’s a testament to John Quincy Adams’ foresight and dedication to preserving not just the ideals of the document, but the document itself.

As President

1825-1829

John Quincy Adams took office as the 6th President of the United States on March 4, 1825. He was the first, but not only, son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence to become President; William Henry Harrison, son of Virginia delegate Benjamin Harrison, was President for a month in 1841 before succumbing to pneumonia. John Quincy Adams was also the first, but not only, son of a former President to become President.

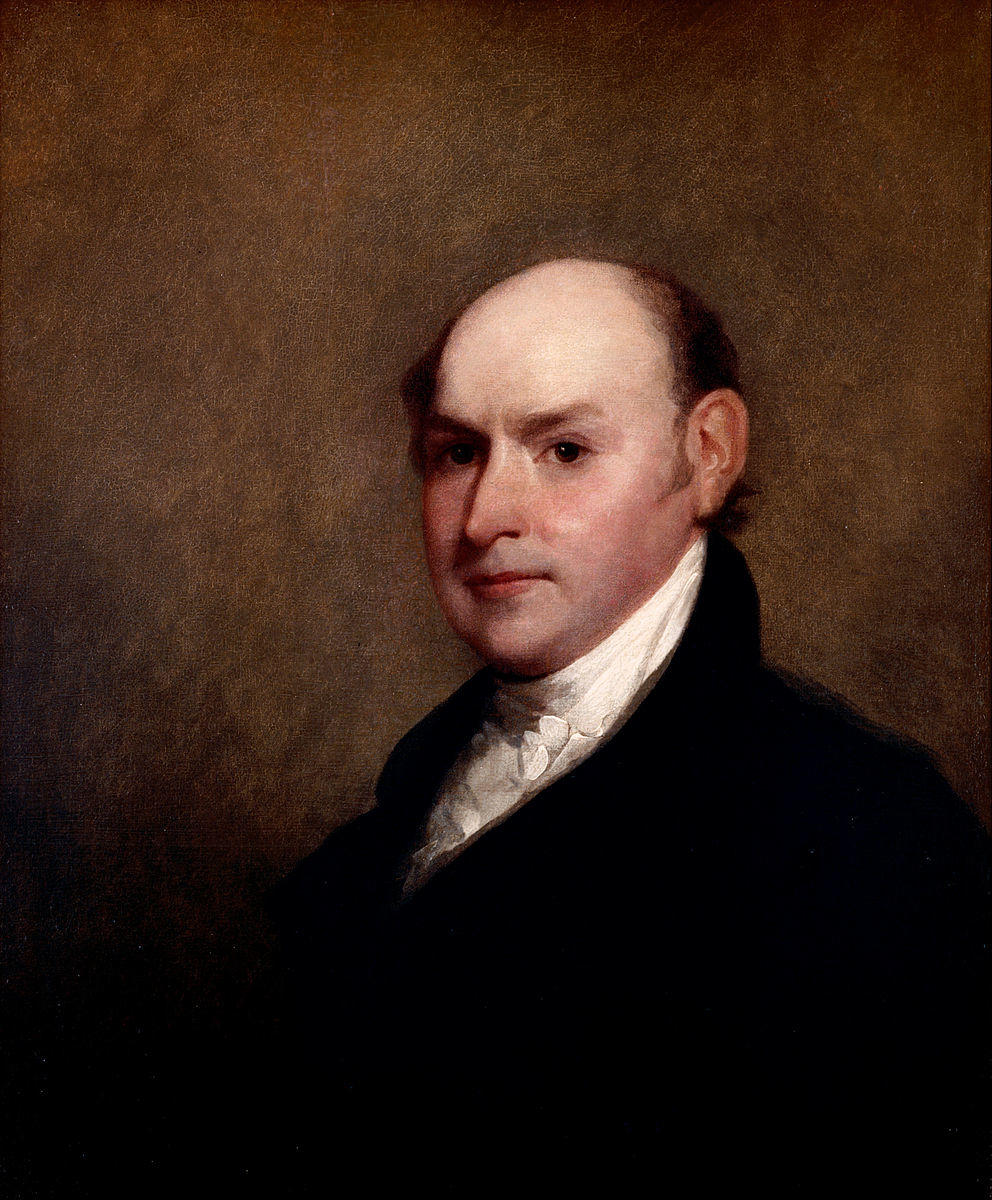

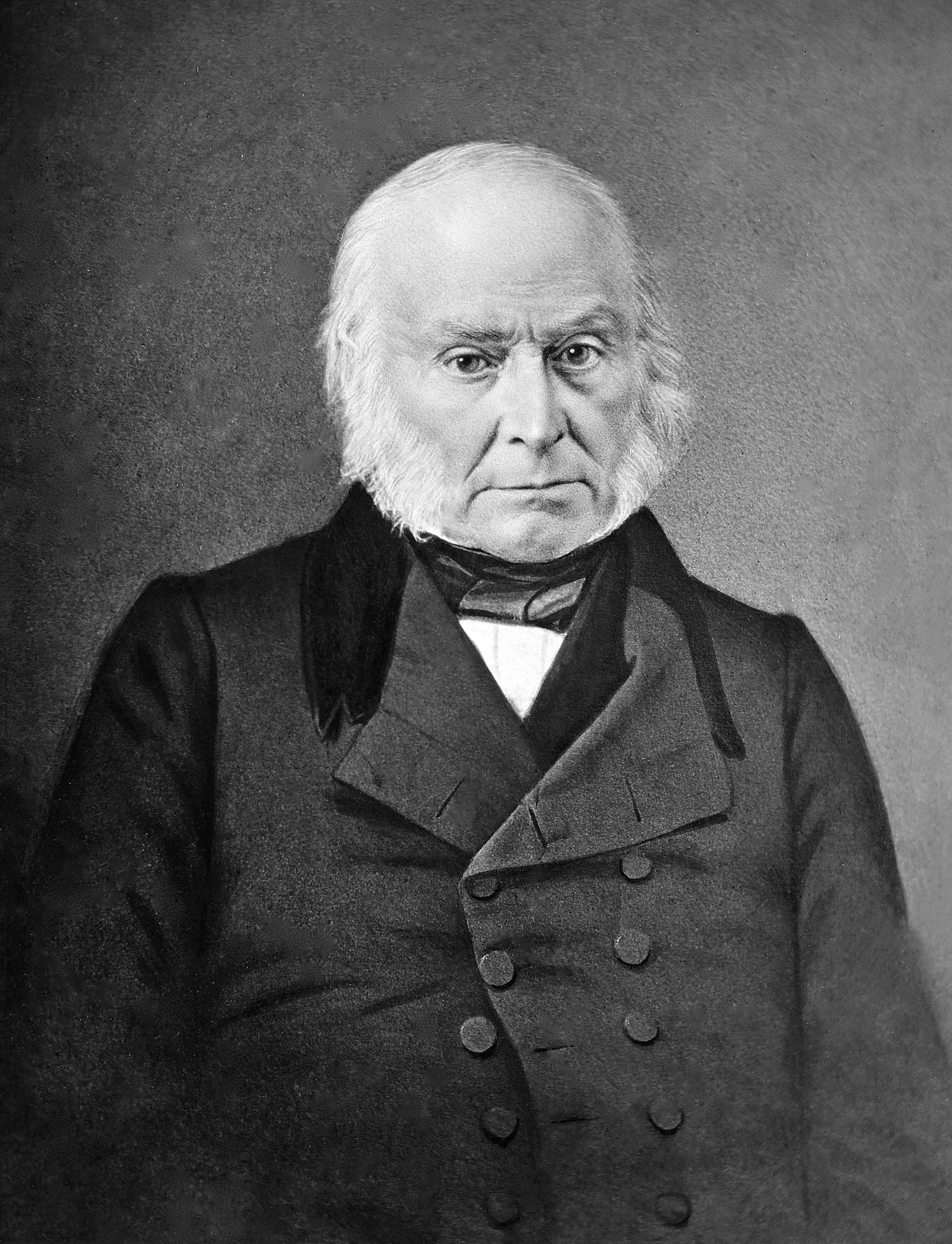

Portraits of John Adams (1826) and John Quincy Adams (1818) by Gilbert Stuart

Just over a year into his term, the country lost two founders and former presidents in one day, and one of those men was the President’s father, John Adams. According to his diary, John Quincy Adams learned of Jefferson’s death on the 6th, since the news only had to travel from Monticello to Washington, D.C. He didn’t learn of his father’s death until the 9th, though he was already on his way home to Massachusetts: “From the Letters which I had yesterday received this event was so much expected by me, that it had no sudden and violent effect on my feelings. My father had nearly closed the ninety-first year of his life a life illustrious in the Annals of his Country and of the World. He had served to great and useful purpose his nation, his Age, and his God... may my last End be like his! It were presumptuous—The time, the manner, the coincidence with the decease of Jefferson are visible and palpable marks of divine favour, for which I would humble myself in grateful and silent adoration before The Ruler of the Universe. For myself all that I dare to ask is that I may live the remnant of my days in a manner worthy of him from whom I come, and at the appointed hour of my maker die as my father has died...”

Six weeks later, John Quincy Adams wrote to his cousin William Cranch, whose father Richard Cranch was Abigail Adams’ brother-in-law:

“The loss of fathers such at least as were yours and mine, is and must be irreparable. Yet it is ‘Nature’s commonest theme,’ and speaking from my own experience it is one of the choicest, as it is among the rarest ingredients of happiness on Earth to have a father yet living till a Son is far advanced in years. This to a certain extent was your good fortune, and it has been much longer mine. It is among the consolations of bereavement, that we are not to endure it long, and we dismiss with more cheerful resignation to the hopes of a better world, the friend whom we are soon to follow there ourselves—

Your letter and the spot where I am, have revived the memory of the scenes of our Childhood, which seem like reminiscences from another world. Before these Politicks vanish, Patriotism itself comparatively fades away, and the Declaration of Independence comes after our walks to Weymouth, and our rides to the Glasshouse at Germantown—The wisdom of the fathers has left traces which have helped us along in our intercourse with the world—but when will be forgotten the tenderness of our mothers? Never till that day shall I cease to be / your affectionate kinsman and friend”

In concluding his State of the Union address (delivered in written form rather than spoken — a Jeffersonian trend) of December 5, 1826, John Quincy Adams took a moment to honor his father and Jefferson, not by name but certainly by spirit:

“Since your last meeting at this place the 50th anniversary of the day when our independence was declared has been celebrated throughout our land, and on that day, while every heart was bounding with joy and every voice was tuned to gratulation, amid the blessings of freedom and independence which the sires of a former age had handed down to their children, two of the principal actors in that solemn scene -- the hand that penned that ever memorable Declaration and the voice that sustained it in debate -- were by one summons, at the distance of 700 miles from each other, called before the Judge of All to account for their deeds done upon earth. They departed cheered by the benedictions of their country, to whom they left the inheritance of their fame and the memory of their bright example.

If we turn our thoughts to the condition of their country, in the contrast of the first and last day of that half century, how resplendent and sublime is the transition from gloom to glory! Then, glancing through the same lapse of time, in the condition of the individuals we see the first day marked with the fullness and vigor of youth, in the pledge of their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to the cause of freedom and of man-kind; and on the last, extended on the bed of death, with but sense and sensibility left to breathe a last aspiration to Heaven of blessing upon their country, may we not humbly hope that to them too it was a pledge of transition from gloom to glory, and that while their mortal vestments were sinking into the clod of the valley their emancipated spirits were ascending to the bosom of their God!”

As a Congressman

1831-1848

In 1834, John Quincy Adams published a speech “on the Removal of the Public Deposites, and its Reasons” that had been suppressed. He called on his colleagues to remember Trumbull’s painting hanging in the Capitol Rotunda (though he was mistaken about it depicting the signing of the Declaration):

“I have asked myself what that small but steadfast band of statesmen and of heroes, whose forms salute us as we daily pass through yonder rotunda to and from this hall, in the very act of signing the Declaration of Independence; I have asked myself what would be their charge to us, their children and descendants, could they speak from the canvass as we pass them by; would they tell us that the summit of human glory is to be scaled by demolishing a Bank? That the benisons of mankind are to be bought by the closure of a broker’s shop? That half a dozen worthy and respectable traders of Philadelphia are tyrannizing over the nation in the guise of Bank directors; and that, unless we take from them the power of loaning money, and calling at the appointed time for its repayment, they will trample our laws, our constitutions, and our liberties, under their feet? Sir, could the patriots of 1776 come down from the side of the wall, enter in solemn procession within these doors, take seats in front of your chair, and witness our deliberations, with what amazement would they learn the propositions submitted to us, and listen to the resolutions prepared for our adoption? Startled, as they well might be, at the shrieks and groans of agonizing freedom which they would hear reverberating within and around this Capitol, would they not inquire, what Attila, what Alaric, what Gengis Khan, had poured his hoards of Goths, of Vandals, or of Tartars, over our fertile fields, our peaceful plantations, and out late flourishing farms? What scourge of God had desolated our cities? What convulsion of nature had palsied the arm of industry? had furled the sails of commerce to mildew at your wharves? had silenced the mill-clap, the shuttle, and the loom? had banished the merchant from the exchange? had severed the ploughman from his plough? the mechanic from his implements of toil? and the daily laborer from his daily bread? Would they not inquire, what is of all this the cause? And how would they blush, or weep, to hear one half of this House respond to their inquiry, the Bank! And the other half, the removal of the deposites!”

In 1837, John Quincy Adams invoked the Declaration in a letter to the inhabitants of his congressional district after he was criticized for presenting a petition from enslaved people in the House:

In 1837, John Quincy Adams invoked the Declaration in a letter to the inhabitants of his congressional district after he was criticized for presenting a petition from enslaved people in the House:

“What are the rights of the South? What is the South? As a component portion of this Union, the population of the South consists of masters, of slaves, and of free persons, white and colored, without slaves. Of which of these classes would the rights be disregarded by the presentation of a petition from slaves? Surely not those of the slaves themselves; the suffering, the laborious, the producing class. Oh, no! there would be no disregard of their rights in the presentation of a petition from them. The very essence of the crime consists in an alleged undue regard for their rights; in not denying them the rights of human nature; in not classing them with horses, and dogs, and cats. Neither could the rights of the free people, without slaves, whether white, black, or colored, be disregarded by the presentation of a petition from slaves. Their rights could not be affected by it at all. The rights of the South, then, here mean the rights of the masters of slaves, which, to describe them by an inoffensive word, I will call the rights of mastery. These, by the Constitution of the United States, are recognized, not directly, but by implication; and protection is stipulated for them, by that instrument, to a certain extent. But they are rights incompatible with the inalienable rights of all mankind, as set forth in the Declaration of Independence; incompatible with the fundamental principles of the constitutions of all the free states of the Union, and therefore, when provided for in the Constitution of the United States, are indicated by expressions which must receive the narrowest and most restricted construction, and never be enlarged by implication.”

As an Author

Later in his life, John Quincy Adams published the Life of General Lafayette… To Which is Added the Life of General Kosciusko and The Lives of James Madison and James Monroe. Although none of these men were directly involved in the Declaration of Independence, Adams invoked the Declaration in both books.

In the Life of General Lafayette, he posited that the Declaration served as Lafayette’s inspiration for joining the American cause: “It was at this stage of the conflict, and immediately after the Declaration of Independence, that it drew the attention, and called into action the moral sensibilities and the intellectual faculties of Lafayette, then in his nineteenth year… In entering upon the threshold of life, a career was to open before him. He had the option of the court and the camp. An office was tendered to him in the household of the king’s brother, the Count de Provence, since successively a royal exile and a reinstated king. The servitude and inaction of a court had no charms for him; he preferred a commission in the army; and at the time of the Declaration of Independence, was a captain of dragoons in garrison at Metz. There, at an entertainment given by his relative, the Marechal de Broglie, the commandant of the place, to the Duke of Gloucester, brother to the British king, and then a transient traveller through that part of France, he learns, as an incident of intelligence received that morning by the English prince from London, that the Congress of Rebels, at Philadelphia, had issued a Declaration of Independence. A conversation ensues upon the causes which have contributed to produce this event, and upon the consequences which may be expected to flow from it. The imagination of Lafayette has caught across the Atlantic tide the spark emitted from the Declaration of Independence; his heart has kindled at the shock, and, before he slumbers upon his pillow, he has resolved to devote his life and fortune to the cause.”

In the Lives of James Madison and James Monroe, Adams suggested that “had he been born ten years before, it can scarcely be doubted that [Monroe] would have been one of the members of the first Congress, and that his name would have gone down to posterity among those of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.” He also compared Madison’s April 1783 address on the plan for restoring public credit to the Declaration:

“My countrymen! do not your hearts burn within you at the recital of these words, when the retrospect brings to your minds the time when, and the person by whom they were spoken? Compare them with the closing paragraphs of the address from the first Congress of 1774, to your forefathers, the people of the Colonies… Compare them both with the opening and closing paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence, too deeply rivited in your memories to need the repetition of them by me; and you have the unity of action essential to all heroic achievement for the benefit of mankind, and you have the character from its opening to its close; the beginning, the middle and the end of that unexampled, and yet unimitated moral and political agent, the Revolutionary North American Congress.”

As an Orator

In 1821, John Quincy Adams was asked to deliver a July 4th address in Washington, D.C. As Secretary of State, and as a negotiator for the Treaty of Ghent, Adams was keenly aware of how the passages about the British people in the Declaration of Independence might be taken by his audience. He urged the crowd:

“Ever faithful to the sentiment proclaimed in the paper [the Declaration of Independence], which I am about to present once more to your memory of the past and to your forecast of the future, you will hold the people of Britain as you hold the rest of mankind,—Enemies in war—in peace, Friends. The conflict for independence is now itself but a record of history. The resentments of that age may be buried in oblivion. The stoutest hearts, which then supported the tug of war, are cold under the clod of the valley. My purpose is to rekindle no angry passion from its embers: but this annual solemn perusal of the instrument, which proclaimed to the world the causes of your existence as a nation, is not without its just and useful purpose.”

After reading the Declaration in full, Adams offered the following analysis:

“It is not, let me repeat, fellow-citizens, it is not the long enumeration of intolerable wrongs con-centrated in this declaration; it is not the melancholy catalogue of alternate oppression and entreaty, of reciprocated indignity and remonstrance, upon which, in the celebration of this anniversary, your memory delights to dwell. Nor is it yet that the justice of your case was vindicated by the God of battles; that in a conflict of seven years, the history of the war by which you maintained that declaration, became the history of the civilized, world; that the unanimous voice of enlightened Europe and the verdict of an after age have sanctioned your assumption of sovereign power, and that the name of your Washington is enrolled upon the records of time, first in the glorious line of heroic virtue. It is not that the monarch himself, who had been your oppressor, was compelled to recognise you as a sovereign and independent people, and that the nation, whose feelings of fraternity for you had slumbered in the lap of pride, was awakened in the arms of humiliation to your equal and no longer contested rights. The primary purpose of this declaration, the proclamation to the world of the causes of our revolution, is ‘with the years beyond the flood.’ It is of no more interest to us than the chastity of Lucretia, or the apple on the head of the child of Tell. Little less than forty years have revolved since the struggle for inde-pendence was closed; another generation has arisen; and in the assembly of nations our republic is already a matron of mature age. The cause of your independence is no longer upon trial. The final sentence upon it has long since been passed upon earth and ratified in heaven.

The interest, which in this paper has survived the occasion upon which it was issued; the interest which is of every age and every clime; the interest which quickens with the lapse of years, spreads as it grows old, and brightens as it recedes, is in the principles which it proclaims. It was the first solemn declaration by a nation of the only legitimate foundation of civil government. It was the corner stone of a new fabric, destined to cover the surface of the globe. It demolished at a stroke the lawfulness of all governments founded upon conquest. It swept away all the rubbish of accumulated centuries of servitude. It announced in practical form to the world the transcendent truth of the unalienable sovereignty of the people. It proved that the social compact was no figment of the imagination; but a real, solid, and sacred bond of the social union. From the day of this declaration, the people of North America were no longer the fragment of a distant empire, imploring justice and mercy from an inexorable master in another hemisphere. They were no longer children appealing in vain to the sympathies of a heartless mother; no longer subjects leaning upon the shattered columns of royal promises, and invoking the faith of parchment to secure their rights. They were a nation, asserting as of right, and maintaining by war, its own existence. A nation was born in a day.”

He then concluded, “In the progress of forty years since the acknowledgement of our Independence, we have gone through many modifications of internal government, and through all the vicissitudes of peace and war, with other mighty nations. But never, never for a moment have the great principles, consecrated by the Declaration of this day, been renounced or abandoned.”

A decade later, in 1831, John Quincy Adams delivered an oration to the town of Quincy, Massachusetts, focusing on the Declaration as a unifying document:

“The Declaration of Independence was a manifesto issued to the world, by the delegates of thirteen distinct, but UNITED colonies of Great Britain, in the name and behalf of their people. It was a united declaration. Their union preceded their independence; nor was their independence, nor has it ever since, been separable from their union. Their language is, “We, the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled, do, in the name and by the authority of the good PEOPLE of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare that these United Colonies, are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” It was the act of one people. The Colonies are not named; their number is not designated; nor in the original Declaration, does it appear from which of the Colonies any one of the fifty-six Delegates by whom it was signed, had been deputed. They announced their constituents to the world as one people, and unitedly declared the Colonies to which they respectively belonged, united, free and independent states. The Declaration of Independence, therefore, was a proclamation to the world, not merely that the United Colonies had ceased to be dependencies of Great Britain, but that their people had bound themselves, before GOD, to a primitive social compact of union, freedom and independence.”

He also proclaimed that the Declaration of Independence was “the crown with which the people of United America, rising in gigantic stature as one man, encircled their brows, and there it remains; there, so long as this globe shall be inhabited by human beings, may it remain, a crown of imperishable glory!”

In 1837, John Quincy Adams addressed the town of Newburyport on the 61st anniversary of the independence, and laid out the main objects of the Declaration:

“The object of this Declaration was two-fold. First, to proclaim the People of the thirteen United Colonies, one People, and in their name, and by their authority, to dissolve the political bands which had connected them with another People, that is, the People of Great Britain. Secondly, to assume, in the name of this one People, of the thirteen United Colonies, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God, entitled them.

With regard to the first of these purposes, the Declaration alleges a decent respect to the opinions of mankind, as requiring that the one people, separating themselves from another, should declare the causes, which impel them to the separation.—The specification of these causes, and the conclusion resulting from them, constitute the whole paper.

The Declaration was a manifesto, issued from a decent respect to the opinions of mankind, to justify the People of the North American Union, for their voluntary separation from the people of Great Britain, by alleging the causes which rendered this separation necessary.

The Declaration was, thus far, merely an occasional state paper, issued for a temporary purpose, to justify, in the eyes of the world, a People, in revolt against their acknowledged Sovereign, for renouncing their allegiance to him, and dissolving their political relations with the nation over which he presided.

For the second object of the Declaration, the assumption among the powers of the earth of the separate and equal station, to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitled them, no reason was assigned,—no justification was deemed necessary.

The first and chief purpose of the Declaration of Independence was interesting to those by whom it was issued, to the people, their constituents in whose name it was promulgated, and to the world of mankind to whom it was addressed, only during that period of time, in which the independence of the newly constituted people was contested, by the wager of battle. Six years of War, cruel, unrelenting, merciless War,—War, at once civil and foreign, were waged, testing the firmness and fortitude of the one People, in their inflexible adherence to that separation from the other, which their Representatives in Congress had proclaimed.”

But he went on to ponder the meaning behind annual celebrations of July 4th:

“Are you then assembled here, my brethren, children of those who declared your National Independence, in sorrow or in joy? In gratitude for blessings enjoyed, or in affliction for blessings lost? In exultation at the energies of your fathers, or in shame and confusion of face at your own degeneracy from their virtues? Forgive the apparent rudeness of these enquiries:—they are not addressed to you under the influence of a doubt what your answer to them will be. You are not here to unite in echoes of mutual gratulation for the separation of your forefathers from their kindred freemen of the British Islands. You are not here even to commemorate the mere accidental incident, that, in the annual revolution of the earth in her orbit round the sun, this was the birth-day of the Nation. You are here, to pause a moment and take breath, in the ceaseless and rapid race of time;—to look back and forward;—to take your point of departure from the ever memorable transactions of the day of which this is the anniversary, and while offering your tribute of thanksgiving to the Creator of all worlds, for the bounties of his Providence lavished upon your fathers and upon you, by the dispensations of that day, and while recording with filial piety upon your memories, the grateful affections of your hearts to the good name, the sufferings, and the services of that age, to turn your final reflections inward upon yourselves, and to say:—These are the glories of a generation past away,—what are the duties which they devolve upon us?”

It makes sense for John Quincy Adams to discuss the Declaration of Independence in depth on the Fourth of July. But even on the Jubilee of the Constitution, April 30, 1839, he delivered an address at the New York Historical Society that was almost just as much about the Declaration as the Constitution:

“Would it be an unlicensed trespass of the imagination to conceive that on the night preceding the day of which you now commemorate the fiftieth anniversary—on the night preceding that thirtieth of April, 1789, when from the balcony of your city hall the chancellor of the State of New York administered to George Washington the solemn oath faithfully to execute the office of the President of the United States, and to the best of his ability to preserve, protect, and defend the constitution of the United States--that in the visions of the night the guardian angel of the Father of our Country had appeared before him, in the venerated form of his mother, and, to cheer and encourage him in the performance of the momentous and solemn duties that he was about to assume, had delivered to him a suit of celestial armor--a helmet, consisting of the principles of piety, of justice, of honor, of benevolence, with which from his earliest infancy he had hitherto walked through life, in the presence of all his brethren; a spear, studded with the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence; a sword, the same with which he had led the armies of his country through the war of freedom to the summit of the triumphal arch of independence; a corselet and cuishes of long experience and habitual intercourse in peace and war with the world of mankind, his contemporaries of the human race, in all their stages of civilization; and, last of all, the Constitution of the United States, a shield, embossed by heavenly hands with the future history of his country?”

L-R: Tombs of John Adams, Abigail Adams, and John Quincy Adams in the crypt of United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts

The “filial piety” John Quincy Adams referenced in so many of these speeches and writings is multidimensional. His pride for his father’s role in the founding of the nation is evident. But Adams also consistently recognizes the role of that second generation, the ones who came after the founders, in preserving the legacy of the notions behind the Declaration of Independence.

When John Quincy Adams himself died, telegraphs allowed for the news to spread quickly. The following day, February 24, 1848, the Salem Register published the following obituary: “In his 81st year, and in the midst of his official duties, John Quincy Adams closes his earthly career. From the cradle to the grave, his whole life has passed in the exercise of the highest trusts, the most honored stations, and the most exalted duties—unscathed, unsuspected and unalloyed. No life was ever more wholly and exclusively devoted to his country than his has been; no trusts were ever more honorably fulfilled.” The memorial continued, “Mr. Adams was descended from the noblest stock—the Nobles of Nature. His mother was one of the first women of her age, and his father the father of our liberties and Constitution—in the emphatic language of Jefferson, ‘the Colossus of Congress, the pillar of support to the Declaration of Independence, and its ablest advocate and defender.’ The son was a legitimate scion of this noble stock. Cradled in the Revolution, and nursed by liberty and patriotism, at nine years of age he heard the Declaration of Independence first read from the Old State House in Boston, and imbibed all its principles.”