The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. In part one, we traced the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. This month, we examine the last 140 years of the Declaration's physical history, from the turn of the century through World War II and the establishment of the National Archives.

The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. In part one, we traced the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. This month, we examine the last 140 years of the Declaration's physical history, from the turn of the century through World War II and the establishment of the National Archives.

1876-1921

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

"The rapid fading of the text of the original Declaration of Independence and the deterioration of the parchment upon which it is engrossed, from exposure to light and lapse of time, render it impracticable for the Department longer to exhibit it or to handle it. For the secure preservation of its present condition, so far as may be possible, it has been carefully wrapped and placed flat in a steel case."

- Department of State, 1894

State, War, and Navy Building, Washington, 1898 photochrom by the Detroit Photographic Co., courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (Digital ID ppmsca 18015)

In April 1876, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish moved the Declaration of Independence into the Department's new fireproof building, which it shared once again with the War and Navy Departments. This building is now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building (formerly the Old Executive Office Building, or OEOB). When the Declaration returned to Washington, D.C. after the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, it was displayed in a cabinet on the east side of the State Department's library in this building. This move proved providential — the Patent Office, where the Declaration had previously been displayed, was destroyed by fire.

In the wake of the centennial, a Joint Resolution of Congress passed in August 1876 calling for a joint commission of representatives from the Smithsonian, Library of Congress, and Interior Department to determine whether it would be possible to restore the ink on the parchment. By 1894, the State Department fully realized both the importance and fragility of the document, and issued the above statement. The conversation about preserving versus restoring the engrossed parchment continues to this day. The National Archives has a number of resources on the conservation history of the Declaration of Independence, including this article by conservators Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Catherine Nicholson, published in 2016.

The Declaration of Independence was taken off view in 1894, but it wasn't completely inaccessible. In 1895, the Coast and Geodetic Survey created a new engraving plate from the engrosed parchment, and in 1898, the parchment was photographed for Ladies Home Journal. Levin C. Handy, who took the first known photograph of the Declaration of Independence in 1883, photographed the parchment again in 1903. In 1904, William H. Michael, author of The Declaration of Independence, reported that the Declaration was "locked and sealed, by order of Secretary Hay, and is no longer shown to anyone except by his direction."

1921-1941

Library of Congress

Washington, D.C.

A 1903 act, under President Theodore Roosevelt, requested that the Department of State hand over records of the Continental Congress to the Library of Congress. But this directive went unfulfilled until a committee created in 1920 reported on the poor state of storage of the Declaration: "the safes are constructed of thin sheets of steel. They are not fireproof nor would they offer much obstruction to an evil-disposed person who wished to break into them." On September 28, 1921, Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes wrote to President Warren G. Harding:

"I enclose an executive order for your signature, if you approve, transferring to the custody of the Library of Congress the original Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States which are now in the custody of this Department... I make this recommendation because in the Library of Congress these muniments will be in the custody of experts skilled in archival preservation, in a building of modern fireproof construction, where they can safely be exhibited to the many visitors who now desire to see them."

The next day, Harding issued an Executive Order authorizing the transfer, adding another reason: "that it is desired to satisfy the laudable wish of patriotic Americans to have an opportunity to see the original fundamental documents upon which rest their Independence and their Government."

Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, indicated to Secretary Hays that the Library was ready to receive the documents. This transfer, a bit more formal than the hasty escape of 1814, consisted of the documents being loaded into the Library's "mail wagon", with leather mail sacks as cushions, and driven to the Library on the other side of the Mall.

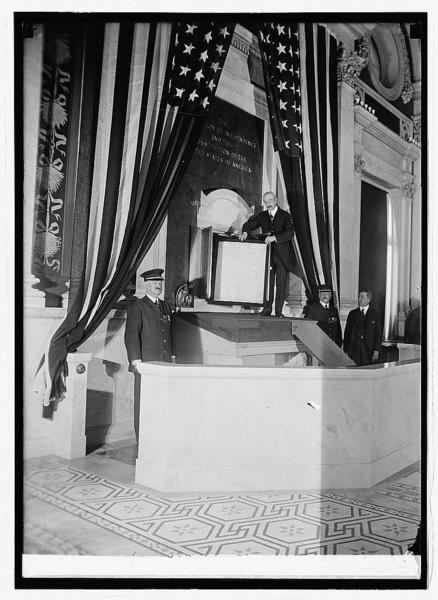

The documents were kept in a safe in Putnam's office while he set to work planning for a permanent installation. What became known as the "shrine" was designed by Francis H. Bacon, brother of Lincoln Memorial architect Henry Bacon, and was located in the Great Hall, on the west side of the second floor of the Library. The Declaration was formally installed on February 28, 1924. With President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge, Secretary of State Hughes, and select members of Congress in attendance, the dedication of the shrine went as follows, according to the February 29th issue of The Washington Post:

Unfurling of the flags revealed the background of grayish black marble, into which was worked the upright frame which was to inclose the Declaration of Independence. Covering this frame were two bronze doors about three feet high. Beneath was the much larger case to hold the Constitution, which had its design in the form of a marble desk. Without a word spoken by anyone in the assembly Mr. Putnam quietly took from the nearby desk the instrument first written and which declared this nation to be free. By means of a small platform that had been built over the lower case he ascended to the height of the upper shrine and opening the bronze doors, placed therein the original copy of the Declaration of Independence. Returning to the floor, the platform was removed and, with the same quiet reverence, he placed the Constitution in the lower case. Then there arose from across the rotunda opening a chorus of employees of the library in the inspiring "America." Gradually the strain was joined in by others prsent, and shortly there was a mass singing that reverberated throughout the corridors and high up to the ceiling and broke the rigid stillness that had gone before. With the completion of this song the President and his party departed, followed by the members of Congress and other invited guests. A few minutes later and the shrine was thrown open to the public.

Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam holding the Declaration of Independence at the dedication, February 28, 1924, https://www.loc.gov/item/npc2008005899/

Less than a decade later, a new option for a permanent home for the Declaration of Independence emerged. In 1933, President Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone for the National Archives building in Washington, D.C., and announced that the Declaration and Constitution would one day reside there. The first Archivist of the United States was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt the following year. Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam objected to moving the documents, which had become a popular attraction for the Library. Connor told Roosevelt to leave the matter alone until Putnam retired, which he did in April 1939. The National Archives building had been completed in 1937, and the new Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish agreed with Roosevelt and Connor that the documents should move there, but because of World War II and because Connor resigned in 1941, the transfer didn't happen.

December 1941-September 1944

Library of Congress

Fort Knox

In April 1941, Archibald MacLeish wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr. about "whether space might perhaps be found" at the Bullion Depository at Fort Knox for the Library's most valuable materials, including the Declaration of Independence, "in the unlikely event that it becomes necessary to remove them from Washington." Morgenthau replied that space would be made available, and eight months later, MacLeish acted on his request. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the Declaration and Constitution were removed from their shrine in the Library of Congress on December 23, 1941 and packed into a specially designed container. The day after Christmas, the documents made their way from Washington, D.C. to Louisville, Kentucky in a Pullman sleeper car, accompanied by the Secret Service. From Louisville, the documents were escorted to Fort Knox and placed in a compartment in the outer tier on the ground level.

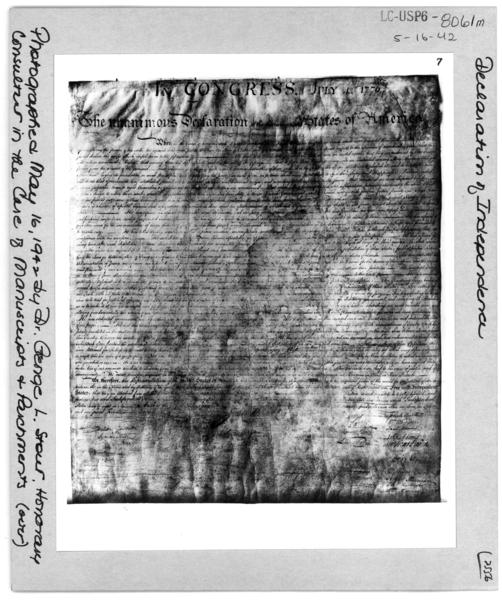

The Library of Congress took advantage of this otherwise nerve-wracking moment away from Washington, D.C. to allow for conservation of the document. In May 1942, the Declaration of Independence was examined and treated by Dr. George L. Stout, Honorary Consultant in the Care of Manuscripts and Parchments, and Mrs. Evelyn Ehrlich, his assistant. Verner Clapp, administrative assistant to the Librarian, sent a report of Stout's work to MacLeish; you can read it here. A year after working on the Declaration, Stout joined the Twelfth Army Group, and was one of the first experts recruited for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section (MFAA), also known as the Monuments Men. In the 2014 Monuments Men film, George Clooney played a character based on Stout.

Photograph of the Declaration of Independence taken by George L. Stout, May 16, 1942, courtesy of the Library of Congress Archives: Photographs, Illustrations, Objects (Number 2556)

The Declaration of Independence remained in Fort Knox until September 1944, which one exception. It returned to Washington, D.C. briefly in April 1943 for the celebration of Thomas Jefferson's bicentenary (April 13) and the dedication of the Jefferson Memorial. The Declaration was placed at the base of the plaster of Paris statue (it would be cast in bronze after the war), with a Marine Honor Guard standing watch.

Photograph of the Jefferson Memorial, April 12, 1943, taken by Ann Rosener, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (Digital ID fsa 8b09941)

1944-1952

Library of Congress

Washington, D.C.

On October 1, 1944, the Declaration of Independence was reinstalled in its shrine in the Library of Congress. As World War II came to a close, the debate over whether to move the Declaration and other founding documents to the National Archives reopened. In 1945, the new Librarian of Congress Luther Evans and the new Archivist of the United States Wayne Grover, both appointed by President Harry S. Truman, agreed that the documents should be transferred to the National Archives building.

1952-Today

National Archives

Washington, D.C.

The Declaration of Independence made its final move on December 13, 1952, and was formally enshrined in the National Archives on December 15th, Bill of Rights Day. In stark comparison to the document's hasty escape from Washington, D.C. in 1814, or even its simple trip by mail truck to the Library of Congress in 1924, this transfer was all pomp and circumstance.

The Declaration of Independence has remained in the Rotunda since 1952. From 2001-2005, as the building was renovated, the Declaration was analyzed by conservators and installed in a new case. In its present location, the Declaration is both safer (even from Nicolas Cage) and more accessible than it has ever been.

The Declaration of Independence in the National Archives, Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs division (Digital ID highsm 15715)

From Charles Thomson through the Department of State, from the Library of Congress to the National Archives, the Declaration of Independence has had quite a few superintendents and quite a few homes. To recap:

- Secretary of Continental Congress/Congress of the Confederation (1776-1789): Charles Thomson

- Secretaries of State (1790-1921): Thomas Jefferson (1790-1793), Edmund J. Randolph (1794-1795), Timothy Pickering (1795-1800), Charles Lee (acting, 1800), John Marshall (1800-1801), Levi Lincoln, Sr. (acting, 1801), James Madison (1801-1809), Robert Smith (1809-1811), James Monroe (1811-1817), John Graham (acting, 1817), Richard Rush (acting, 1817), John Quincy Adams (1817-1825), Daniel Brent (acting, 1825), Henry Clay (1825-1829), James A. Hamilton (acting, 1829), Martin Van Buren (1829-1831), Edward Livingston (1831-1833), Louis McLane (1833-1834), John Forsyth (1834-1841), Jacob L. Martin (acting, 1841), Daniel Webster (1841-1843; 1850-1852), Hugh S. Legaré (acting, 1843), William S. Derrick (acting, 1843), Abel P. Upshur (1843-1844), John Nelson (acting, 1844), John C. Calhoun (1844-1845), James Buchanan (1845-1849), John M. Clayton (1849-1850), Charles M. Conrad (acting, 1852), Edward Everett (1852-1853), William Hunter (acting, 1853), William L. Marcy (1853-1857), Lewis Cass (1857-1860), William Hunter (acting, 1860), Jeremiah S. Black (1860-1861), William H. Seward (1861-1869), Elihu B. Washburne (1869), Hamilton Fish (1869-1877), William M. Evarts (1877-1881), James G. Blaine (1881; 1889-1892), Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen (1881-1885), Thomas F. Bayard (1885-1889), William F. Wharton (acting, 1892, 1893), John W. Foster (1892-1893), Walter Q. Gresham (1893-1895), Edwin F. Uhl (acting, 1895), Richard Olney (1895-1897), John Sherman (1897-1898), William R. Day (1898), Alvee A. Adee (acting, 1898), John Hay (1898-1905), Francis B. Loomis (acting, 1905), Elihu Root (1905-1909), Robert Bacon (1909), Philander C. Knox (1909-1913), William Jennings Bryan (1913-1915), Robert Lansing (1915-1920), Frank Polk (acting, 1920), Bainbridge Colby (1920-1921), Charles Evans Hughes (1921-1925)

- Directors of the United States Patent Office (not technically superintendents, but, the Declaration was in their office 1841-1876): Henry L. Ellsworth (1835-1845), Edmund Burke (1845-1849), Thomas Ewbank (1849-1852), Silas H. Hodges (1852-1853), Charles Mason (1853-1857), Joseph Holt (1857-1859), William Darius Bishop (1859-1860), Philip F. Thomas (1860), David P. Halloway (1861-1865), Thomas Clarke Theaker (1865-1868), Elisha Foote (1868-1869), Samuel S. Fisher (1869-1870), Mortimer D. Leggett (1871-1874), John M. Thacher (1874-1875), Robert H. Duell (1875-1877)

- Librarians of Congress (1921-1952): Herbert Putnam (1899-1939), Archibald MacLeish (1939-1944), Luther Evans (1945-1953)

- Archivists of the United States (1952-present): Wayne C. Grover (1948-1965), Robert H. Bahmer (1965-1968), James B. Rhoads (1968-1979), James O'Neill (1979-1980), Robert M. Warner (1980-1985), Frank Burke (1985-1987), Don W. Wilson (1987-1993), Trudy Huskamp Peterson (1993-1995), John W. Carlin (1995-2005), Allen Weinstein (2005-2008), Adrienne Thomas (2008-2009), David S. Ferriero (2009-present)

The Declaration of Independence has spent time in six different states (Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Kentucky), in addition to the District of Columbia, where it has spent the majority of the last two centuries. The furthest north and east the engrossed parchment has ever travelled is New York City; the furthest south and west is Fort Knox, Kentucky. Its current encasement at the National Archives is set to last for another eighty-some years, beyond the 250th anniversary of the Fourth of July (2026 - just nine years away!), Jefferson's tricentenary (2043) and even the tricentennial (2076). But don't wait until then to visit! The Rotunda at the National Archives is open seven days a week, nearly every day of the year, and admission is always free.

For more information:

- National Archives, The Declaration of Independence: A History

- Carting the Charters - Online Exhibit by the National Archives and Google Arts & Culture

- Carting the Charters blog

By Emily Sneff