Founding Fathers. Founders. Fathers. Founding Mothers. Signers. Framers. Patriots. The list of terms to describe the individuals who "founded" the United States of America can go on and on. This month, we examine the etymology and accuracy of these terms, and find where the signers of the Declaration of Independence fit in.

Founding Fathers. Founders. Fathers. Founding Mothers. Signers. Framers. Patriots. The list of terms to describe the individuals who "founded" the United States of America can go on and on. This month, we examine the etymology and accuracy of these terms, and find where the signers of the Declaration of Independence fit in.

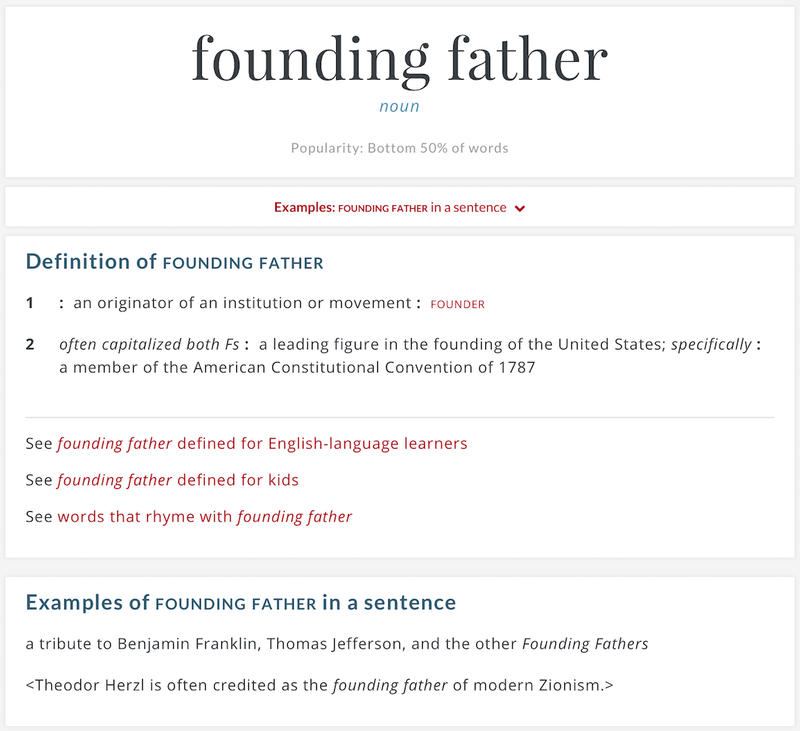

Merriam-Webster

founding father (n): 1. an originator of an institution or movement; 2. often capitalized both Fs: a leading figure in the founding of the United States; specifically a member of the American Constitutional Convention of 1787

Oxford English Dictionary

founding (adj): Associated with or marking the establishment of (something specified); that originated or created. Spec. founding father (freq. with capital initials), an American statesman of the Revolutionary period, esp. a member of the American Constitutional Convention of 1787

Safire's Political Dictionary (1968, 2008)

Founding Fathers: A group of revolutionaries who took their changes on treason to pursue the course of independency, who are today viewed reverently as sage signers of the documents of U.S. freedom.

The common thread: statesmen, and more specifically, delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. However, if we use this definition, several men who are indisputably "Founding Fathers" are left out. Even Merriam-Webster's sample sentence falls into the trap of this narrow definition — see if you can spot the problem:

That's right: if we narrow the definition of Founding Father to "member of the American Constitutional Convention of 1787", we exclude Thomas Jefferson, since he did not attend the Constitutional Convention. And he's not the only one. Other men who frequently come to mind as founders — John Adams, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry, to name a few — are not Founding Fathers by this definition. And only eight signers of the Declaration of Independence attended the Constitutional Convention: Roger Sherman, George Clymer, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris, James Wilson, George Read, George Wythe (resigned in June), and Elbridge Gerry (refused to sign).

Scene at the Signing of the United States Constitution, Howard Chandler Christy, 1940

If we use this specific definition, "Founding Father" is essentially equivalent to "framer", and both terms leave out dozens of individuals who represent the values upon which the nation was founded. And, in fact, it was this context of invoking the spirit of the "Founding Fathers" that led to the popularization of the term — far more recently than you might think.

Warren G. Harding popularized "Founding Father" a century ago, in his keynote address at the 1916 Republican National Convention.1 Harding was a senator from Ohio at the time, and chairman of the convention, which nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes (who ultimately lost to Woodrow Wilson). Here is the term in context, as reported by The Boston Herald on June 8, 1916: "No political party ever has builded or even can build permanently except in conscientious devotion to abiding principles. Time never alters a fundamental truth. Conditions do change, popular interest is self-assertive, and ‘paramounting’ has its perils, as the Democratic party will bear witness, but the essentials of constructive government and attending progress are abiding and unchanging. For example, we ought to be as genuinely American today as when the founding fathers flung their immortal defiance in the face of old-world oppressions and dedicated a new republic to liberty and justice. We ought to be as prepared for defence as Washington urged amid the anxieties of our national beginning, and Grant confirmed amid the calm reflections of union restored." This wasn't the only time Harding used the term. In remarks delivered to the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution in 1918, Harding said, "It is good to meet and drink at the fountains of wisdom inherited from the founding fathers of the Republic." He also frequently used the term during his campaign for the presidency in 1920; for example, "Let's hold fast to that which has come to us from the founding fathers, from the union, from those who awakened us to a little finer conscience, then get off this detour on the right track again and go ahead." And, once Harding became President, he used the term in his inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1921: "Standing in this presence, mindful of the solemnity of this occasion, feeling the emotions which no one may know until he senses the great weight of responsibility for himself, I must utter my belief in the divine inspiration of the founding fathers."

Warren G. Harding popularized "Founding Father" a century ago, in his keynote address at the 1916 Republican National Convention.1 Harding was a senator from Ohio at the time, and chairman of the convention, which nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes (who ultimately lost to Woodrow Wilson). Here is the term in context, as reported by The Boston Herald on June 8, 1916: "No political party ever has builded or even can build permanently except in conscientious devotion to abiding principles. Time never alters a fundamental truth. Conditions do change, popular interest is self-assertive, and ‘paramounting’ has its perils, as the Democratic party will bear witness, but the essentials of constructive government and attending progress are abiding and unchanging. For example, we ought to be as genuinely American today as when the founding fathers flung their immortal defiance in the face of old-world oppressions and dedicated a new republic to liberty and justice. We ought to be as prepared for defence as Washington urged amid the anxieties of our national beginning, and Grant confirmed amid the calm reflections of union restored." This wasn't the only time Harding used the term. In remarks delivered to the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution in 1918, Harding said, "It is good to meet and drink at the fountains of wisdom inherited from the founding fathers of the Republic." He also frequently used the term during his campaign for the presidency in 1920; for example, "Let's hold fast to that which has come to us from the founding fathers, from the union, from those who awakened us to a little finer conscience, then get off this detour on the right track again and go ahead." And, once Harding became President, he used the term in his inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1921: "Standing in this presence, mindful of the solemnity of this occasion, feeling the emotions which no one may know until he senses the great weight of responsibility for himself, I must utter my belief in the divine inspiration of the founding fathers."

In each of Harding's uses, "founding fathers" is a term imbued with morals, responsibility, and devotion. It is also catchy, and according to William Safire, Harding was fond of alliterative phrases (or, as Safire phrased it, "'Founding Fathers' functioned as the fulfillment of his forensic fancy."). But Harding never defined the specific men described by this term; in fact, in his 1916 RNC speech, Harding references both George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first citation for the term "founding fathers" is the title of Kenneth Umbreit's 1941 book, Founding Fathers: Men Who Shaped Our Tradition. Umbreit highlights John Adams, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington — that's four signers of the Declaration of Independence. In 1973, Richard B. Morris wrote Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries, and included among his seven "Founding Fathers" John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington — that's three signers of the Declaration. The most recent article on the Founding Fathers in the Encyclopedia Britannica, written by Joseph J. Ellis, lists ten men: John Adams, Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Marshall, George Mason, and George Washington — again, just four signers of the Declaration of Independence.2 Each of the signers included in these narrow lists of "Founding Fathers" is also, arguably, remembered more for their other contributions to the early United States than for their act of signing the Declaration of Independence.

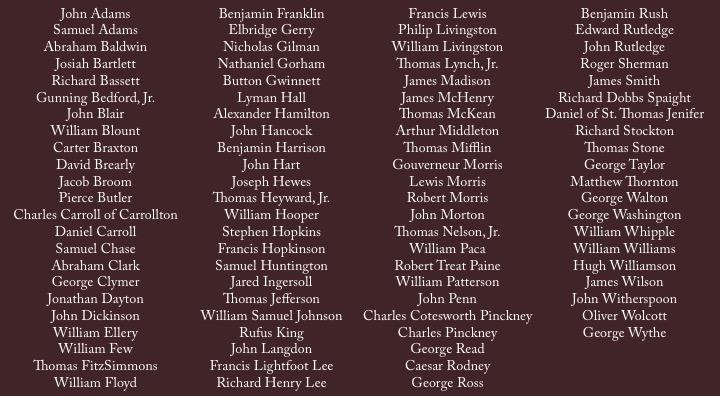

Should the signers of the Declaration of Independence count as "Founding Fathers"? Let's try painting with a broader brush. If you combine the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence with the thirty-nine signers of the United States Constitution (keeping in mind that six men signed both documents), you get eighty-nine "Founding Fathers". But even this list leaves out two of the three men who refused to sign the Constitution (Edmund Randolph and George Mason), along with notable individuals such as John Jay and Patrick Henry, not to mention heroes of the Revolutionary War, and ignores entirely the women who played pivotal roles in the founding of the nation. And this list, as you can see, includes a number of relatively unknown individuals who would hardly be at the top of a Family Feud-style survey about the "Founding Fathers":

While the term "Founding Fathers" seems to be a 20th-century creation, the concept of revering individuals who contributed to the founding of the nation began in the early 19th century, when several of them were still living. In an oration delivered in 1825, Daniel Webster acknowledged the loss of the founding generation: "Those who established our liberty and our government are daily dropping from among us. The great trust now descends to new hands. Let us apply ourselves to that which is presented to us, as our appropriate object. We can win no laurels in a war for independence. Earlier and worthier hands have gathered them all. Nor are there places for us by the side of Solon, and Alfred, and other founders of states. Our fathers have filled them. But there remains to us a great duty of defense and preservation; and there is opened to us, also, a noble pursuit, to which the spirit of the times strongly invites us."

Unlike "founding fathers", which seems so closely associated with the Constitutional Convention, the term "fathers" has a deeper connection to the signers of the Declaration of Independence. In "The Present Aspect of the Slavery Question" in 1859, George William Curtis referred to the men who created the Declaration of Independence as "our fathers". A few years later came perhaps the most famous use of the term: "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." If "all men are created equal" isn't enough of a clue, "four score and seven" equals eighty-seven, so Lincoln (speaking in 1863) was referring to 1776.

In their own time, the last living signers of the Declaration of Independence were referred to as founders, but also as patriots, and often described as "illustrious" or "immortal" (an adjective also used by Harding), or a "band of patriots". In 1818, Benjamin Owen Tyler wrote to John Adams about his "elegant copy of the Declaration of American Independence" with facsimiles of the signatures "of that ever venerated band of patriots". Tyler's glowing letters are full of phrases describing the founders: "those Heroes, Statesman, and patriots, who achieved our Independence", "most sanguine heroes of the revolution", "those sages who signed that invaluable document", "the fathers of American Liberty".

Charles Carroll of Carrollton died on November 14, 1832, and the November 16th issue of Poulson's American Daily Advertiser announced his death as follows: "CHARLES CARROLL of CARROLLTON is no more! The last of the Signers is dead! The only remaining link which connected this generation with the past, with that illustrious race of statesmen, philanthropists and patriots, the founders of American Independence, and the benefactors of the world, now and for all time hereafter—is broken. The brotherhood of glory is reunited above, and Carroll is removed from the love, gratitude and veneration of the living, to an association with the kindred spirits of Washington, and his associated, the departed patriarchs of Liberty. Henceforth, the Declaration of Independence is sacred to History—part of the mighty Past. The last of the Signers is dead."

The following eulogy was also published in the newspapers, including Poulson's American Daily Advertiser:

"The last of the Romans," —

The last of that

Sacred Band

Who in the darkest hour of their country's struggle

Peril'd their lives, their fortunes, and their honour

For her Freedom;—

CHARLES CARROLL, of Carrollton,

The venerated and beloved;—

The Virtuous and the Wise,

The Patriot and the Christian —

Is no more! 3

Historically, "the last of the Romans" has been used to describe the last representative of Ancient Roman values, and the first recorded use of the term was Brutus mourning Cassius in Plutarch's Parallel Lives. With the death of Carroll, Americans felt a disconnect to the men who signed the Declaration of Independence which was summarized by this ancient epithet, this recognition that the Declaration of Independence and its signers were "sacred to History—part of the mighty Past." "The last of the Romans" was invoked a year earlier,4 when James Monroe died on July 4, 1831 (five years exactly after Adams and Jefferson had died), and again when James Madison died in 1836. Though, after Madison's death, some newspapers printed corrections since Paine Wingate, who represented New Hampshire in the Continental Congress in 1788, still survived (he died in 1838).

Although we are focused on the signers of the Declaration of Independence, who were all men, we would be remiss if we didn't heed Abigail Adams' call to "Remember the ladies." Mary Beth Norton and Cokie Roberts, among others, have written about "Founding Mothers" — though Norton focuses on the first half-century of English colonization — and the term has gained popularity as a way to acknowledge the wives, sisters, daughters, and female associates of the men generally considered "Founding Fathers" who made their own impacts on the founding of the nation. In addition to these women, consider, for example, the female printers who published editions of the Declaration of Independence, most notably Mary Katharine Goddard.

Today, founders is perhaps the most widely accepted term. It encompasses not just the signers and framers, and not just the men, but all individuals who played important roles in the founding of the United States of America. Going back once again to Harding, and even earlier to John Quincy Adams, several presidents have used their inaugural addresses to invoke the spirit of the "founders":

- John Quincy Adams, 1825: "It is a source of gratification and of encouragement to me to observe that the great result of this experiment upon the theory of human rights has at the close of that generation by which it was formed been crowned with success equal to the most sanguine expectations of its founders."

- Rutherford B. Hayes, 1877: "I ask the attention of the public to the paramount necessity of reform in our civil service — a reform not merely as to certain abuses and practices of so-called official patronage which have come to have the sanction of usage in the several Departments of our Government, but a change in the system of appointment itself; a reform that shall be thorough, radical, and complete; a return to the principles and practices of the founders of the Government."

- James A. Garfield, 1881: "Under this Constitution the boundaries of freedom have been enlarged, the foundations of order and peace have been strengthened, and the growth of our people in all the better elements of national life has indicated the wisdom of the founders and given new hope to their descendants."

- Grover Cleveland, 1885: "On this auspicious occasion we may well renew the pledge of our devotion to the Constitution, which, launched by the founders of the Republic and consecrated by their prayers and patriotic devotion, has for almost a century borne the hopes and the aspirations of a great people through prosperity and peace and through the shock of foreign conflicts and perils of domestic strife and vicissitudes."

- Warren G. Harding, 1921: "We have seen the world rivet its hopeful gaze on the great truths on which the founders wrought."

- Jimmy Carter, 1977: "Two centuries ago our Nation's birth was a milestone in the long quest for freedom, but the bold and brilliant dream which excited the founders of this Nation still awaits its consummation. I have no new dream to set forth today, but rather urge a fresh faith in the old dream."

- Bill Clinton, 1993: "When our founders boldly declared America's independence to the world and our purposes to the Almighty, they knew that America, to endure, would have to change. Not change for change's sake, but change to preserve America's ideals — life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. Though we march to the music of our time, our mission is timeless."

- Bill Clinton, 1997: "We — the American people — we are the solution. Out founders understood that well and gave us a democracy strong enough to endure for centuries, flexible enough to face our common challenges and advance our common dreams in each new day. ... Our founders taught us that the preservation of our liberty and our union depends upon responsible citizenship."

For more on this topic:

- Journal of the American Revolution, How Do You Define "Founding Fathers"?, 2015

- The JuntoCast, Episode 15: Founders in Early America

- Ben Franklin's World, Episode 58: Andrew Schocket, Fighting over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution

- Andrew M. Schocket, Fighting over the Founders: How We Remember the American Revolution, 2015

- R.B. Bernstein, The Founding Fathers Reconsidered, 2009

1. At the 1912 Republican National Convention, Harding used the term "founding American fathers", but the first recorded use of his preferred alliterative phrase "founding fathers" was in 1916. See R.B. Bernstein, The Founding Fathers Reconsidered.

2. Ellis delightfully notes, "there is a nearly unanimous consensus that George Washington was the Foundingest Father of them all."

3. The poem continues, "He has gone down to the grave, 'Full of days, riches, and honor.' Of no distemper, of no blast he died, But fell like autumn fruit; that mellow'd long, E'en wonder'd at, because he dropp'd no sooner: Fate seem'd to wind him up for fourscore years, Yet freshly ran he fifteen winters more, Till like a clock worn out by eating time, The wheels of weary life, ast last stood still."

4. See, for example, the July 8, 1831 issue of the Salem Gazette, which refers to the New York Commercial Advertiser from earlier in the week.

Thanks to our Twitter followers who provided input for this blog post! If you have a comment about the etymology of these terms, leave it here, or tweet us @declarationres.

By Emily Sneff