The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. This month, we trace the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. Stay tuned for part two (1877-today) in February!

The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. This month, we trace the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. Stay tuned for part two (1877-today) in February!

1776

Continental Congress

Philadelphia

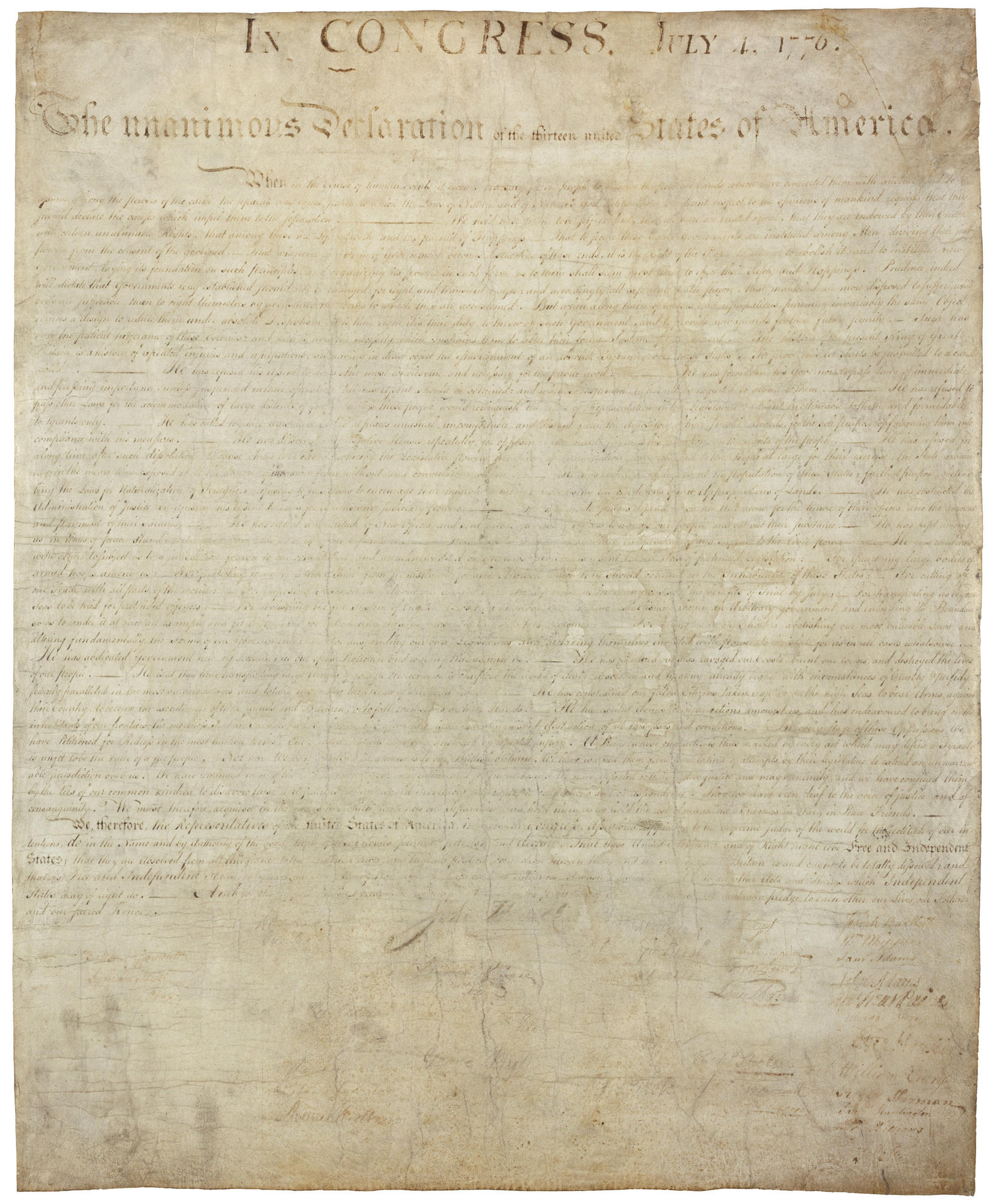

On July 19, 1776, the Continental Congress resolved, "That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Timothy Matlack likely took on this task, and on August 2nd, in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, the engrossed parchment was signed by the majority of the 56 delegates.

1776-1789

Continental Congress/Congress of the Confederation

Philadelphia -> Baltimore -> Philadelphia -> Lancaster -> York -> Philadelphia -> Princeton -> Annapolis -> Trenton -> New York City

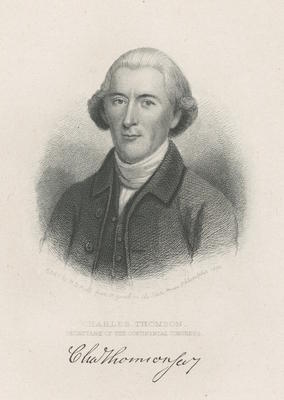

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (Image at right courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections). Thomson had been unanimously chosen as Secretary of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774. When the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775, Thomson was once again chosen as its Secretary. He stayed with the Congress as it transitioned into the Congress of the Confederation (under the Articles of Confederation), serving as secretary to the Congress for nearly 15 years, and counting among his responsibilities the care of the papers of the Congress (including the Declaration of Independence).

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (Image at right courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections). Thomson had been unanimously chosen as Secretary of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774. When the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775, Thomson was once again chosen as its Secretary. He stayed with the Congress as it transitioned into the Congress of the Confederation (under the Articles of Confederation), serving as secretary to the Congress for nearly 15 years, and counting among his responsibilities the care of the papers of the Congress (including the Declaration of Independence).

If the Declaration stayed with Thomson, then it is likely that it moved with the Congress, as he did. The first move came in December 1776, when the Congress evacuated Philadelphia and reconvened at the Henry Fite House in Baltimore, Maryland later that month. In January 1777, the engrossed parchment -- at least the signatures at the bottom -- likely served as a resource for Mary Katharine Goddard as she created her "authentic copy" of the Declaration. In March 1777, the Continental Congress returned to Independence Hall in Philadelphia, but only for a few months. In September 1777, Congress met for a day at the court house in Lancaster, Pennsylvania before moving further west to the court house in York, Pennsylvania. In July 1778, Congress returned to Independence Hall, this time for a few years. In June 1783, the Congress of the Confederation fled the Pennsylvania Mutiny and relocated to Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey. A few months later, in November 1783, the Congress reconvened at the State House in Annapolis, Maryland. In November 1784, the Congress met at the French Arms Tavern in Trenton, New Jersey for a month before adjourning and moving to New York. From January 11, 1785 through 1789, the Congress of the Confederation met in New York City, at City Hall (which later became Federal Hall) and at Fraunces Tavern.

Over the course of these thirteen years in the care of Charles Thomson, the engrossed parchment (assuming it stayed with the Congress through each of these moves) found a home in four different states, and spent a total of about six years at its first home, Independence Hall. The transition of custody that came with the establishment of the Federal Government would bring the Declaration back to Philadelphia and, ironically, back under the care of the man who drafted those engrossed words.

1790-1800

Department of State

Philadelphia -> Washington, D.C.

"Having had the honor of serving in quality of Secretary of Congress from the first meeting of Congress in 1774 to the present time, a period of almost fifteen years, and having seen in that eventful period, by the interposition of divine Providence the rights of our country asserted and vindicated, its independence declared acknowledged and fixed, peace & tranquility restored & in consequence thereof a rapid advance in arts, manufacturing and population, and lastly a government established which gives well grounded hopes of promoting its lasting welfare & securing its freedom and happiness, I now wish to return to private life. With this intent I present my self before you to surrender up the charge of the books, records, and papers of the late Congress which are in my custody & deposited in rooms of the house where the legislature assemble, and to deliver into your hands the Great Seal of the federal Union, the keeping of which was one of the duties of my Office..."

- Letter from Charles Thomson to George Washington, July 23, 1789

Charles Thomson retired in July 1789, and sent the above letter of resignation to President Washington, who responded, "I have to regret that the period of my coming again into public life, should be exactly that, in which you are about to retire from it." Washington instructed Thomson to "deliver the Books, Records & Papers of the late Congress--the Great Seal of the Federal Union--and the Seal of the Admiraly, to Mr Roger Alden, the late Deputy Secretary of Congress; who is requested to take charge of them until farther directions shall be given." Thomson handed over custody of the Great Seal (which he had a hand in designing) and all the papers, including the Declaration of Independence, to Alden, who soon became a clerk in a new agency.

On July 21, 1789, two days before Thomson retired, Congress approved the establishment of a Department of Foreign Affairs, and it was signed into law by President Washington on July 27th -- the first federal agency created under the U.S. Constitution. In September 1789, the name and duties were changed, and this agency became the Department of State. This new department was entrusted with the records of the Continental Congress and the Congress of the Confederation, including the Declaration of Independence. On September 26, 1789, President Washington appointed the first Secretary of State: Thomas Jefferson. That's right -- the man remembered as author of the Declaration of Independence was now the official custodian of the engrossed parchment.

On July 16, 1790, an act of Congress called for the relocation of the seat of government from New York City to Philadelphia for a length of ten years, from the first Monday in December of 1790 to the first Monday in December of 1800 (though that end date would later be moved up to May). The papers of the State Department were transferred, some by land and some by water, to Philadelphia. From October 1790 through April 1793, the State Department's offices were located in a building on the north side of Market Street between Eighth and Ninth Streets, conveniently opposite the house where Jefferson lived for much of his time as Secretary of State. Between 1793 and 1800, the State Department offices moved a few more times: first, in April 1793, to a larger building on the north side of Market Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets; then, in May 1794, to a building on the corner of Sixth and Arch Streets; then, in October 1796, to a building on North Alley (now part of Cuthbert Street), between Market and Arch, and between Fifth and Sixth Streets.

In 1945, a plaque was placed at the Market Street entrance to the Strawbridge & Clothier department store in Philadelphia, commemorating the site of Jefferson's office as Secretary of State. Image courtesy of Temple University Libraries; click here for more.

Jefferson intended to resign as Secretary of State in September 1793, but at Washington's request, he stayed on until the end of the year. Edmund Jennings Randolph succeeded Jefferson as Secretary of State, but resigned in August 1795. Washington's third Secretary of State, Timothy Pickering, served from 1795 until May 1800, when he was dismissed by President John Adams. From November 1797 through May 1800, the Department of State was located in a building on the east side of Fifth Street between Market and Chestnut Streets, which it shared with the office of the Postmaster General. In the falls of 1797, 1798, and 1799, Pickering moved the department to the New Jersey State House in Trenton, New Jersey because of repeated outbreaks of yellow fever in Philadelphia. Adams' dismissal of Pickering and the department's move to Washington, D.C. in May 1800 ushered in a new era for the State Department, and for the Declaration of Independence.

1800-1814

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

On May 28, 1800, acting Secretary of State Charles Lee left Philadelphia, and he arrived in Washington, D.C. a few days later. From June-August 1800, the State Department and the Declaration of Independence was located in a building intended for the Treasury Department, located where the Treasury Department Building is today, on 15th Street just east of the White House. In September 1800, the State Department moved into one of the "Six Buildings", on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets NW.

After Adams dismissed Pickering, Charles Lee served as interim Secretary of State for a month before John Marshall became Secretary of State. When President Thomas Jefferson took office on March 4, 1800, Levi Lincoln, Sr., served as Secretary of State for two months before James Madison took over. A good friend of the president, Madison was Jefferson's Secretary of State for almost all of Jefferson's presidency. In May 1801, after Madison assumed the duties of Secretary, the State Department moved to a new building west of the White House, located where the Eisenhower Executive Office Building is today. Over the next thirteen years, the State Department shared this building with both federal and city agencies, including the Patent Office and the War and Navy Departments.

1814

Department of State

Leesburg, Virginia

1876 engraving, "Capture and Burning of Washington by the British, in 1814", courtesy of the Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs Division (Digital ID cph.3c17176)

The War of 1812 began while the State Department was located in the building west of the White House. When Madison succeeded Jefferson as President of the United States in 1809, Robert Smith succeeded Madison as Secretary of State. Two years later, Madison appointed future President of the United States James Monroe as Secretary of State. It was Monroe who saw the British fleet in the Chesapeake Bay in August 1814. He ordered the Department of State to evacuate all of the records from the capital. A clerk named Stephen Pleasonton has been given credit for saving the Declaration of Independence and the rest of the state papers (which included, for the record, the Constitution, the Journals of the Continental Congress, and the laws and treaties of the United States). Pleasonton packed the papers in linen bags and carted them to a grist mill two miles upriver from Georgetown, before continuing on to Leesburg, Virginia, thirty-five miles from Washington, D.C. On August 24, 1814, when the British burned the capital, the Declaration of Independence was safe in Leesburg. The papers of the State Department returned to Washington, D.C. in September 1814 after the British withdrew from the Chesapeake.

1814-1841

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

"The foregoing copy of the declaration of Independence, has been collated with the original instrument and found correct. I have, mysely, examined the signatures to each. Those executed by Mr Tyler are curiously exact imitations; so much so that it would be difficult if not impossible for the closest scrutiny to distinguish them, were it not for the hand of time, from the originals."

- Acting Secretary of State Richard Rush, on Benjamin Owen Tyler's Facsimile of the Engrossed Parchment

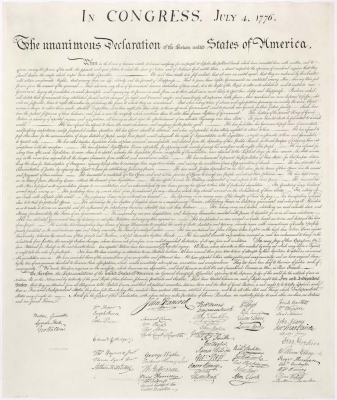

Many public buildings were destroyed by the British, including the previous home of the Department of State. In September 1814, the State Department moved temporarily to a house on the south side of G Street between 17th and 18th Streets NW. In April 1816, the department was able to move to the rebuilt public building west of the White House, which was shared, once again, with the War and Navy Departments; the department remained there through August 1819. In the wake of the war, patriotism surged, and the American people became increasingly interested in the founding generation and the Declaration of Independence. During this time, several engravings of the Declaration of Independence were produced, one by John Binns in 1818 and one by Benjamin Owen Tyler in 1819. On September 10, 1817, acting Secretary of State Richard Rush (son of Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Rush, and grandson of signer Richard Stockton) applauded Tyler's work, in the above note of authentication which can be seen on Tyler's facsimile.

Engravings of the Declaration of Independence produced in the 1810s-1820s, L-R: Benjamin Owen Tyler, 1819; John Binns, 1818; William J. Stone, 1823

Rush was succeeded by John Quincy Adams (son of signer and former President John Adams), who served as Secretary of State from September 1817-March 1825. John Quincy Adams provided the following authentication for Binns' facsimile on April 19, 1819: "I certify, that this is a CORRECT copy of the original Declaration of Independence, deposited at this Department; and that I have compared all the signatures with those of the original, and have found them EXACT IMITATIONS." Binns' facsimile wasn't the only one created under Adams' watch. In 1820, Adams commissioned William J. Stone to create an exact facsimile of the engrossed parchment. Three years later, Stone completed his meticulous work, and 200 copies of his facsimile were struck and presented to members of Congress, dignitaries, and the living signers of the Declaration of Independence.

1841-1876

Department of State/Patent Office

Washington, D.C.

On June 11, 1841, Secretary of State Daniel Webster wrote to Commissioner of Patents Henry L. Ellsworth about relocating the Declaration of Independence to the new Patent Office building at Seventh and F Streets. Ellsworth granted the request, and the Declaration and George Washington's Commission as Commander and Chief were mounted in a single frame and displayed in a hall in the building. This was the first truly public display of the Declaration, which had previously only been accessible through appointments with the Secretary (of Congress, and then of State). The documents remained on display in the Patent Office building through the Civil War and even after the Patent Office was separated from the Department of State and incorporated into the Department of the Interior.

"United States Patent Office, Washington, D.C., showing F Street facade, possibly taken from the upper floor of the General Post Office", ca. 1846, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (Digital ID cph.3g03596)

1876

Mayor William S. Stokley

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

From May 10-November 10, 1876, Philadelphia hosted the Centennial Exposition, the first World's Fair held in the United States. The Exposition was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and despite hesitations about the fragility of the document, President Ulysses S. Grant granted temporary custody of the engrossed parchment to Philadelphia Mayor William S. Stokley so that the Declaration could be a part of the Exposition. The Declaration was transported to Philadelphia and displayed for the length of the exhibition, and was even read aloud on July 4, 1876 by Richard Henry Lee (grandson of the signer). This marks the last time the engrossed parchment was in Independence Hall.

"The Fourth of July at Philadelphia: Mr. Richard Henry Lee Reading the Original Document of the Declaration of Independence", courtesy of the Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs Division (Digital ID cph.3a50763)

When the engrossed parchment returned to Washington, D.C., and to the custody of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, it was moved into a new fireproof building. To find out about this new home and the life and travels of the Declaration of Independence from 1877 to today, see our February Highlight: Superintending Independence, Part 2!

For more information:

- National Archives, The Declaration of Independence: A History

- Office of the Historian, Department of State

By Emily Sneff