The Sussex Declaration

General Information about the Sussex Declaration

Key Facts:

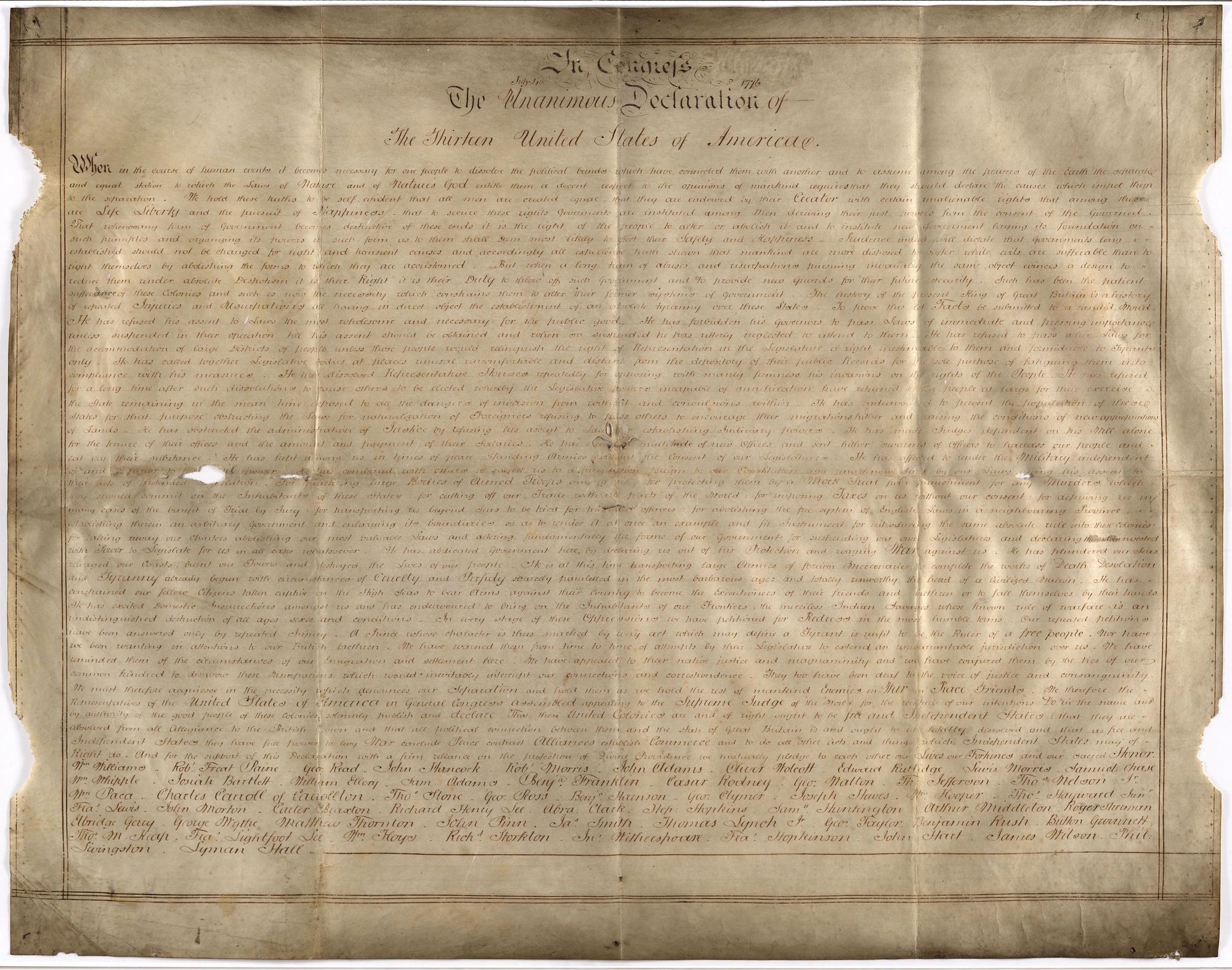

- Housed at the West Sussex Record Office in Chichester, UK; uncovered by the Declaration Resources Project in August 2015

- The only known parchment manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence apart from the engrossed and signed parchment in the National Archives (referred to herein as the Matlack Declaration). Both words—"parchment" and "manuscript"—are important. There are other parchment copies that were printed; these are the only two parchment copies that were handwritten. There are also other handwritten copies of the Declaration, for instance, with the text written out on letter-sized paper for private circulation. The Matlack Declaration and the Sussex Declaration are the only two parchment manuscript copies of the Declaration.

- Measures 24" x 30", the same size as the Matlack Declaration, but oriented horizontally

- Interesting features include marginal ruling, decorative penwork around the titling, evidence of nail holes, and justified, round hand script

- The list of the names of the signers is not in state order, as was typical; the names are scrambled, and several are misspelled

-

Material evidence dates the parchment manuscript to the late 18th century

April 2017 Press Release | July 2018 Press Release

Click here for images of the Sussex Declaration and related documents (see the "Please Read" document for image permissions and credits).

Please direct all all press inquiries to Peter Reuell, and all inquiries about the Sussex Declaration to Emily Sneff.

Materials Related to July 2018 Press Release:

British Library - Scientific Imaging Technical Report

British Library - XRF Technical Report

Library of Congress Report

Memo - Declaration Resources Project, Summary of Research Trip, August 2017

Our research on the Sussex Declaration includes three components:

-

Dating the parchment manuscript using material evidence

"The Sussex Declaration: Dating the Parchment Manuscript of the Declaration of Independence Held at the West Sussex Record Office (Chichester, UK)"

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 112, no. 3 (September 2018)

-

Determining who commissioned the parchment manuscript and why

"Golden Letters: James Wilson, the Declaration of Independence, and the Sussex Declaration"

Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 17, no. 1 (Winter 2019)

-

Identifying when and how the parchment manuscript moved from the United States to the United Kingdom

Research currently in progress: The Sussex Declaration was possibly held by the Third Duke of Richmond (1735-1806). Known as the "Radical Duke" for his support of the Americans during the Revolution, his county seat is in Sussex in the UK. The parchment manuscript was deposited at the West Sussex Record Office with other papers from the Dukes of Richmond's law firm. The parchment is, however, American and, given its dating, is most likely to have been produced in New York or Philadelphia. While the parchment may have moved to the UK in the 1780s or 1790s, when the Third Duke could have received it, it is also possible that it moved to the UK only after 1836. An engraving was made from it, or from an identical text, in Boston in that year.

Document Genres Related to Sussex Declaration

The Sussex Declaration is styled with a distinctive use of parallel ruled lines along all four edges of the parchment, which cross in the corners forming squares. The large, centered title is characterized by decorative penwork. In addition, several words in the parchment are emphasized by being written in a larger size with thicker pen strokes and more ink. Finally, the parchment is prepared horizontally, not vertically.

The Sussex Declaration is styled with a distinctive use of parallel ruled lines along all four edges of the parchment, which cross in the corners forming squares. The large, centered title is characterized by decorative penwork. In addition, several words in the parchment are emphasized by being written in a larger size with thicker pen strokes and more ink. Finally, the parchment is prepared horizontally, not vertically.

These four stylistic features derive from the textual genre of legal documents, specifically:

- Property deeds produced in Britain, from the middle of the 17th century onward

- Property deeds produced in the American colonies and the new United States from the middle of the 18th century onward

- Credentials for delegates to Congress from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and New Jersey produced between 1780 and 1790

Importantly, all of these document types were frequently prepared in landscape orientation.

In the new republic, four states—Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and New Jersey—appear to have drawn on the pre-existing tradition of property deeds to develop a form for official state documents and, in particular, for credentials for delegates serving in new national governing bodies. The documentary context for securing property rights appears to have provided the aesthetic forms necessary to imbue new state documents with legitimacy.

As is not surprising, the British and American traditions for these document types diverge in the period just before the American Revolution. Documents from each tradition continue to have a family resemblance to one another but there are also clear differences. Those differences concern ink and titling.

Differences in Ink

Figure 1: Two land indentures from Exeter, England, 1768 and 1769. Lot #94004, Weekly Internet Rare Books and Autographs Auctions #201427, Heritage Auctions.

Beginning in the middle of the 18th century, British deeds began to make regular use of red ink for the ruled parallel lines. Typically, American property deeds seem not to use red ink. Notable exceptions are documents produced on behalf of the Penn family by the Pennsylvania Land Office between 1760 and 1776 (see the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania State Archives for examples).

Rubrication in printed material was quite rare in the American colonies in the 18th century because of the difficulty of securing and producing red inks, and it appears that rubrication was also rare on manuscripts. Among the credentials for delegates, only the New York examples use red ink for the ruled parallel lines, and the ink appears to have been some sort of home-brewed substitute for the bright British scarlet ink. (For more information, see Frederick R. Goff, Rubrication in American Books of the Eighteenth Century, 1969)

Differences in Titling

The more important divergence between British and American documents concerns titling. British property deeds align the deed title with the left-hand margin. Some American deeds and credentials use left-justified titling, but others employ centered titling.

British property deeds have decorative penwork around the title from the 1760s. This stylistic feature does not transfer into the American tradition of property indentures, which maintain plain titling throughout the 18th century. However, Congressional credentials do adopt the practice of employing decorative penwork around the document title. The earliest American parchment documents that we have found with similar penwork are John Jay’s credentials for the Continental Congress in 1778 and a printed representation of such penwork in the Philadelphia military commission in 1779.

Figure 2: New York General Assembly, Credentials of John Jay as a delegate, 1778. Miscellaneous Papers of the Continental Congress, Record Group 360, National Archives and Records Administration. Available on Fold3, Credentials of delegates to the Congress from New York, 1775-87 and 1778-89, page 53, frame number 502.

Figure 3: Commission appointing John Greaton colonel of the 3d Massachusetts, to rank as such from July 1, 1775, 1779. MssCol 927, Thomas Addis Emmet Collection, Series XIII, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

The style of Jay’s credentials imitates the decorated British property deeds, as one can see by comparing the highly decorated initial “T” of both documents. Massachusetts and New York delegates’ credentials from the 1780s also have this element of decorative titling, as do documents produced by the Bank of North America and by the North American Land Company, both of which were founded by Robert Morris, signer of the Declaration, Articles, and Constitution and Superintendent of Finance for the new republic from 1781-1784.

Figure 4: Detail, Credentials of Samuel Holten as a Mass. delegate, 1782. Miscellaneous Papers of the Continental Congress, Record Group 360, National Archives and Records Administration. Available on Fold3, Credentials of delegates to the Congress from Massachusetts, 1774-88, page 52, frame number 274.

Despite the clear stylistic connection between Jay’s credential document and the British property deeds, however, the traditions soon diverge. In the 1770s and 1780s, American penwork in these sorts of documents became less elaborate and tended more often to be symmetrical, while the British penwork seemed more frequently to deploy asymmetry and the higher degree of elaboration that we see in the example from the 1760s.

American property deeds are modelled on pre-1760s British property deeds, while American state documents are modelled on a slightly later stage of British property deed. Like the New York credentials, the Sussex Declaration draws on the pre-existing tradition of British, colonial, and American property indentures for the formatting of the document in landscape orientation with ruled parallel lines to define the margins. The Sussex Declaration, however, in its use of relatively simple and symmetrical decorative penwork around the titling, belongs to the tradition of American state documents that developed in the 1770s and 1780s.

The calligraphy on the Sussex Declaration most closely resembles the calligraphy on Pennsylvania and New York documents. The titling styling of the Sussex Declaration bears an especially strong resemblance to the titling for the Charter of the Bank of North America, produced in 1781. The scribal hand of the fair copy clerk appears to be that of a clerk trained either in a legal or mercantile context. The fact that the clerk has prepared the document horizontally is strong evidence that his typical practice focused on property deeds, where large, horizontal parchments were regularly prepared in the late 18th century.

The Sussex Declaration's styling belongs to the tradition of American legal and mercantile documents from the 1770s and 1780s. These details align with a dating from the use of the mercantile round hand to the late 18th century.

For more, download Allen and Sneff, "The Sussex Declaration: Dating the Parchment Manuscript of the Declaration of Independence Held at the West Sussex Record Office (Chichester, UK)", under final revision and preparatin for publication at Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America.

By Danielle Allen and Emily Sneff

Stabilization of the Names of the Signers

In the 1780s and 1790s, a handful of interested parties were dissatisfied with the state of the print record of the Declaration. One glaring inconsistency was the inclusion of Thomas McKean’s name. McKean signed the Declaration of Independence sometime after Mary Katherine Goddard’s broadside (1777) and Robert Aitken and John Dunlap’s Journals of the Continental Congress (1777 and 1778, respectively) were printed with his name excluded. The first printing to include McKean’s name came from Francis Bailey in 1782, but even then, his name was inserted in the wrong place in the list of Delaware signatories.

In 1791, Francis Childs and John Swaine were authorized to consult the original rolls of the Continental Congress, and clearly did so. Their Acts of Congress and Laws of the United States were the first printings of the Declaration of Independence not only to include McKean’s name, but also to place it in the proper order within the Delaware signatories. Nonetheless, other 1791 printings including Andrew Brown’s Laws of the United States of America, failed to include McKean.

In 1793, the very first printer of the Declaration of Independence, John Dunlap, visited the archives himself to determine once and for all what the list of signatories should be. Between 1786 (the tenth anniversary of the Declaration) and 1792, Dunlap had reprinted the Declaration in his newspaper on July 4th nearly every year, excluding McKean’s name in each printing. For the July 4, 1793 edition, he helpfully appended this note:

“In several former publications of the declaration of Independence, the list of names was taken from the Journals of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Vol. I. wherein there appears to have been a material omission in the list of names, by leaving out that of Thomas McKean, our present Chief Justice of the State of Pennsylvania. In order to prevent any further misrepresentation on that head, we have searched for the Original Instrument in the office of the Secretary of State for the United States, and there found Mr. McKean’s name amongst the signers to that great and glorious Record! We now give the list of names from the original parchment.”

In other words, in 1791 printers began consulting the original rolls to stabilize the tradition of representing the signatories, but until 1793, even frequent printer of the Declaration of Independence John Dunlap was confused about which names should be on the list.

From one other source we can identify further satisfaction during the 1780s with the print record of the Declaration. On June 1, 1783, Thomas Jefferson, writing from Monticello, sent a letter to James Madison, then in Philadelphia, in which he enclosed, at Madison’s request, a fresh manuscript copy of the “original” Declaration as Congress had passed it. In his letter to Madison, Jefferson also indicated the changes that Congress had made to his initial draft. That Madison, who served in Congress in 1781-1783, should have wanted this copy indicates that, despite his access as a member of Congress to Bailey’s 1781 book printing, he was not satisfied with the print record. Like McKean, who challenged the printings that left off his name, and Dunlap who eventually checked the original instrument, Madison was curious about what the original had to say. McKean’s interest in correcting the record and Madison’s curiosity are small indications that some of the leading participants in the day’s political conversations did not find the officially sanctioned print texts sufficient for their needs.

1791 to 1793 were the watershed years. Up until that period, interested parties had reasons to refer to original documents to determine what the Continental Congress of 1776 had signed and who had done so. Thereafter, authenticated versions, like the Childs and Swaine and Dunlap printings, were available. Yet stabilizing the tradition of reproducing the Declaration was not an easy matter. The variants without McKean’s name persisted in roughly equal numbers to those with his name.

The presence of Thomas McKean's name on the Sussex Declaration suggests that, if the parchment was produced in the 1780s or 1790s as other material evidence suggests, the source text must have also included McKean's name among the signatories.

For more, download Allen and Sneff, "The Sussex Declaration: Dating the Parchment Manuscript of the Declaration of Independence Held at the West Sussex Record Office (Chichester, UK)", under final revision and preparatin for publication at Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America.

By Danielle Allen and Emily Sneff

Why Signing Order Mattered: The Constitutional Convention

When the majority of the delegates signed the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776, they signed in state order, from New Hampshire through Georgia, and from right to left. As other men returned to or arrived at Congress, they added their names within those state groupings; the exception being Matthew Thornton. However, the state groupings were not labeled. Why did signing order matter for documents such as the Declaration of Independence? The debates a decade later at the Constitutional Convention give context.

On Monday September 17, the last day of the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin, who earlier in the Convention had invoked the need to follow the example of the men who had deliberated and decided on the Declaration of Independence, led off the debates by making a proposal for signature (see Farrand's Records, vol. 1, pp. 444-452). James Madison recorded Franklin’s words thus:

“On the whole, Sir, I cannot help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility--and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument. -- He then moved that the Constitution be signed by the members and offered the following as a convenient form viz. “Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present the 17th. of Sepr. &c -- In Witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.” (see Farrand's Records, vol. 2, pp. 641-649)

Madison then added the following additional commentary: “This ambiguous form had been drawn up by Mr. G. M. in order to gain the dissenting members, and put into the hands of Docr. Franklin that it might have the better chance of success.” Franklin’s formulation, a clever effort at compromise, was “ambiguous” in that it served to blur the distinction between a mode of signature that would express the unanimity of a group of individual men and a mode that would instead smooth over dissent by attributing the unity to the states, not individuals.

Although there was resistance to signing from some, Franklin’s motion succeeded in the end, and nearly everyone signed the Constitution. Those who signed did so not as individuals but as representatives of their states, and on the Constitution the state labels are written in alongside each group of signatures.

The method used for the Declaration of Independence on the Matlack parchment did not elide the state-by-state voting procedure but did reduce its prominence and also simultaneously conveyed the commitment of each signer as an individual. The Declaration was unanimous among the states but also at the level of the individual men signing it, who pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor in the final sentence. (Those who disagreed, like John Dickinson, had been obliged to leave Congress.) In contrast, the method used for signing the Constitution placed the emphasis on the decision of each of the thirteen states, only. The purpose of Franklin’s “ambiguous formula” was to enable men who did not want to endorse the instrument itself nonetheless to express their support, as members of their state delegations, for moving the document on to Congress. Yet his formula did not satisfy everyone. The three exceptions who did not sign were senior statesmen: George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, and Edmond Randolph. Gerry had signed the Declaration of Independence, and he and Randolph chose not to sign the Constitution on the grounds that they did not want to be personally bound to defending the new instrument.

For more, download Allen and Sneff, "The Sussex Declaration: Dating the Parchment Manuscript of the Declaration of Independence Held at the West Sussex Record Office (Chichester, UK)", under final revision and preparatin for publication at Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America.

By Danielle Allen and Emily Sneff