The Declaration of Independence was an act of treason. The men that signed the parchment Declaration of Independence, now in the National Archives, were literally pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. They knew that their support of an act of independence would come back to haunt them if the British defeated George Washington and the Continental Army. If you take a closer look at a broadside printed in January 1777 by order of the Continental Congress, you'll notice another name committed to the cause. Not a signer, but a printer. Not a man, but a woman. Meet Mary Katherine Goddard, printer and postmaster to the Second Continental Congress in Baltimore.

The Declaration of Independence was an act of treason. The men that signed the parchment Declaration of Independence, now in the National Archives, were literally pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. They knew that their support of an act of independence would come back to haunt them if the British defeated George Washington and the Continental Army. If you take a closer look at a broadside printed in January 1777 by order of the Continental Congress, you'll notice another name committed to the cause. Not a signer, but a printer. Not a man, but a woman. Meet Mary Katherine Goddard, printer and postmaster to the Second Continental Congress in Baltimore.

Goddard was born in New London, Connecticut in 1739, the daughter of the local doctor and postmaster. When her younger brother William (1740-1817) started a printing business in Providence, Rhode Island, Mary Katherine and their mother, Sarah, joined William and learned the trade. William Goddard started Providence's first newspaper, the Providence Gazette, which he then abandoned and which his mother then resurrected in partnership with John Carter. Mary Katherine and Sarah then followed William to Philadelphia, where he began the ill-fated Pennsylvania Chronicle in 1767. After Sarah's death, William and Mary Katherine relocated to Baltimore, where William Goddard started the city's first newspaper, the Maryland Journal and the Baltimore Advertiser, in 1773.

"Baltimore is a very pretty Town, situated on Petapsco River, which empties itself into the great Bay of Chesapeak. The Inhabitants are all good Whiggs, having sometime ago banished all the Tories from among them. The Streets are very dirty and miry, but every Thing else is agreeable..." - John Adams to Abigail Adams, 2 February 1777

In Baltimore, Mary Katherine Goddard flourished, partly due to her brother's constantly shifting priorities, but mostly due to her own skill and determination. William Goddard left the Maryland Journal after about a year in order to travel the colonies to promote his "Constitutional Post," an alternative to the royal postal system. When William's plan was put into effect in July 1775, Mary Katherine was named postmaster of Baltimore. She was the first postmaster of Baltimore, the first female postmaster in the colonies, and shortly thereafter the first female postmaster in the United States of America.

As a burgeoning port city roughly equidistant from New York and Williamsburg, Baltimore's post office was surely one of the busiest in the colonies-turned-United States. Mary Katherine not only managed the post as efficiently as possible (given the limitations of travel time, mail carriers, secrecy, and the ongoing war), but she also continued to print the Maryland Journal as well as pamphlets, broadsides and books, and sold other printed and blank materials. At about the same time she was named postmaster, Mary Katherine stopped printing the Maryland Journal under her brother's name, and began printing it under an abbreviated (and androgynous) name, "M.K. Goddard," taking ownership and also responsibility for the contents of her work. She was the first woman to print the text of the Declaration of Independence, in the July 10th issue of the Maryland Journal. But her biggest moment -- as both a printer and a postmaster -- came in December 1776.

In mid-December, with British troops closing in on the city of Philadelphia, the Continental Congress evacuated to Baltimore. Mary Katherine Goddard was suddenly responsible for all incoming and outgoing mail for the delegates to the Congress, for printing one of only two newspapers in the city, and for printing other miscellaneous documents, including Congressional broadsides. She continued to act as a bookseller as well, even selling blank books to John Adams. Her print shop/bookstore/post office was located just blocks away from the meeting place of Congress, called the Henry Fite House.

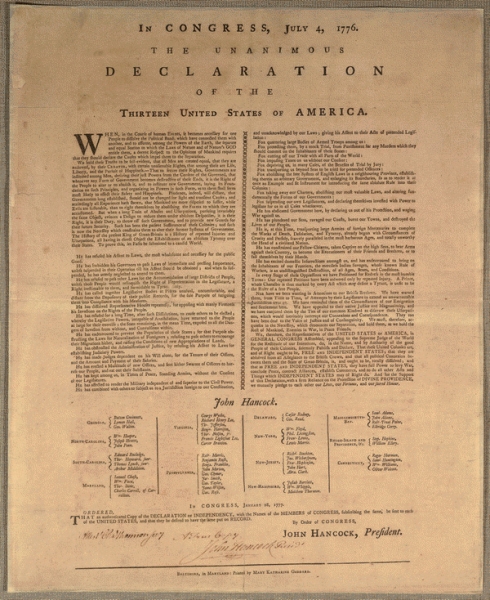

Goddard printed several resolutions and notices by order of Congress in December 1776 and January 1777 before being tasked with printing a particularly special document. On January 18th, 1777, the Journals of the Continental Congress record the following order: "That an authenticated copy of the Declaration of Independency, with the names of the members of Congress subscribing the same, be sent to each of the United States, and that they be desired to have the same put upon record." Mary Katherine Goddard was tasked with printing these broadsides, and completed the order within two weeks. On January 31st, President of Congress John Hancock sent a broadside to each of the states, accompanied by the following letter:

"As there is not a more distinguished Event in the History of America, than the Declaration of her Independence--nor any that in all Probability, will so much excite the Attention of future Ages, it is highly proper that the Memory of that Transaction, together with the Causes that gave Rise to it, should be preserved in the most careful Manner that can be devised. I am therefore commanded by Congress to transmit you the enclosed Copy of the Act of Independence with the List of the several Members of Congress subscribed thereto and to request, that you will cause the same to be put upon Record, that it may henceforth form a Part of the Archives of your State, and remain a lasting Testimony of your approbation of that necessary & important Measure."

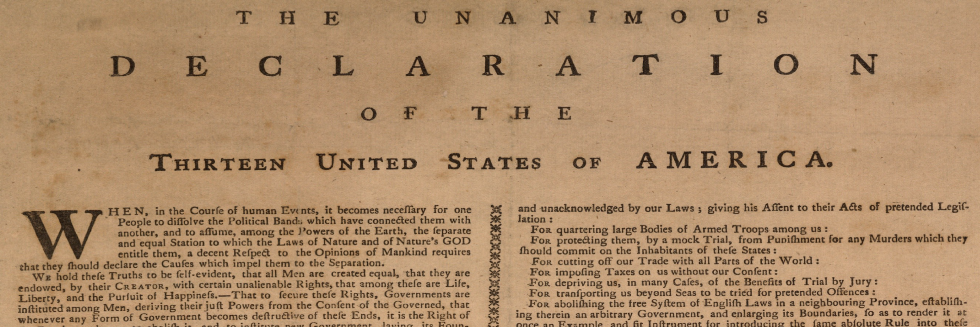

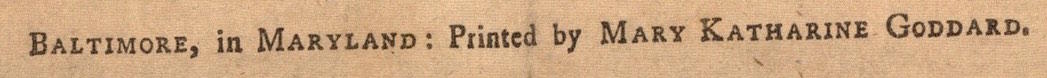

The Goddard Broadside was the first printed version of the Declaration of Independence specifically intended for preservation. It was the first printed broadside to use the title "The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America". It was the first version of the Declaration to list the names of (most of) the signers. And, it is the only "official" version of the Declaration of Independence to be printed by a woman. Mary Katherine Goddard's imprint at the bottom of her broadside proudly presents not only her full name, but also the city where Congress met for two crucial months, and where she lived and worked for over forty years.

As for Mary Katherine Goddard, she printed the Maryland Journal until 1779, when her brother resumed control of the paper in partnership with Eleazer Oswald. Mary Katherine continued her own printing and bookselling business in Baltimore until her death in 1816. She also continued to serve as postmaster for Baltimore until 1789. After the ratification of the Constitution, the new Postmaster General Samuel Osgood removed Goddard from her position. His reasons were likely political, but were interpreted by Goddard and the public as patronizing and sexist. The only reason given by Osgood was that the position would require more travel and time on the road than a woman would presumably be able to handle. Backed by over 200 prominent citizens of Baltimore, Mary Katherine took her complaint to the highest authority -- President George Washington. Though unsuccessful, her petition is preserved in the National Archives as a testament to her tenacity and devotion to the city of Baltimore.

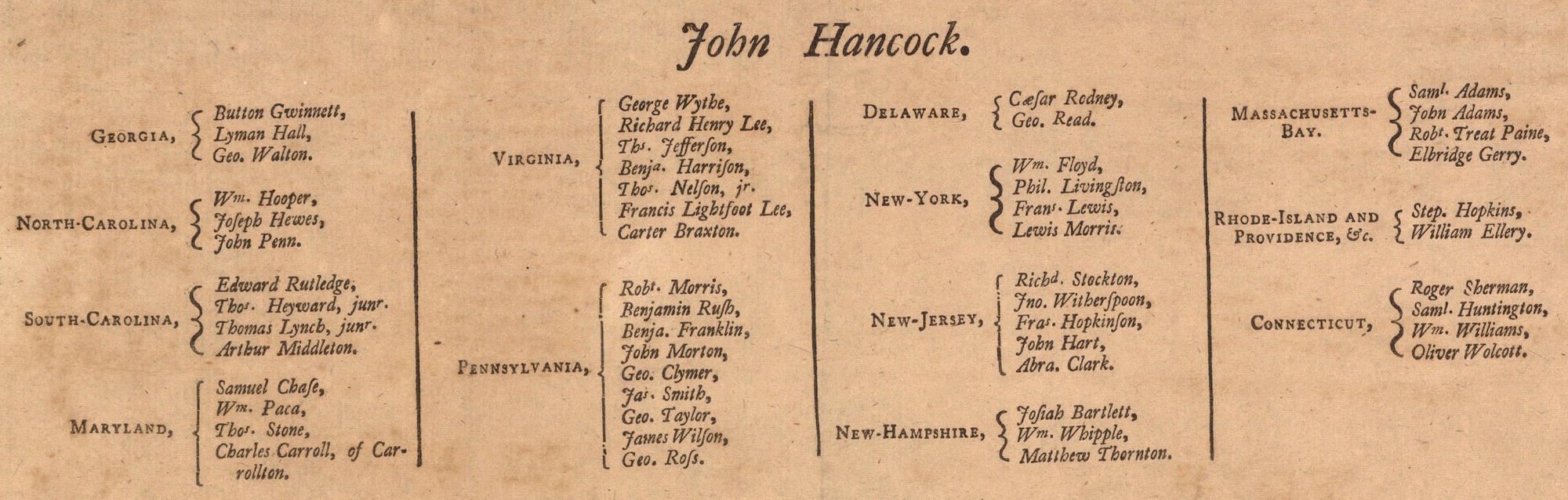

Closer Look: The Signers

The Goddard Broadside lists 55 of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence. The missing name is Thomas McKean, who likely signed the Declaration of Independence after January 1777.

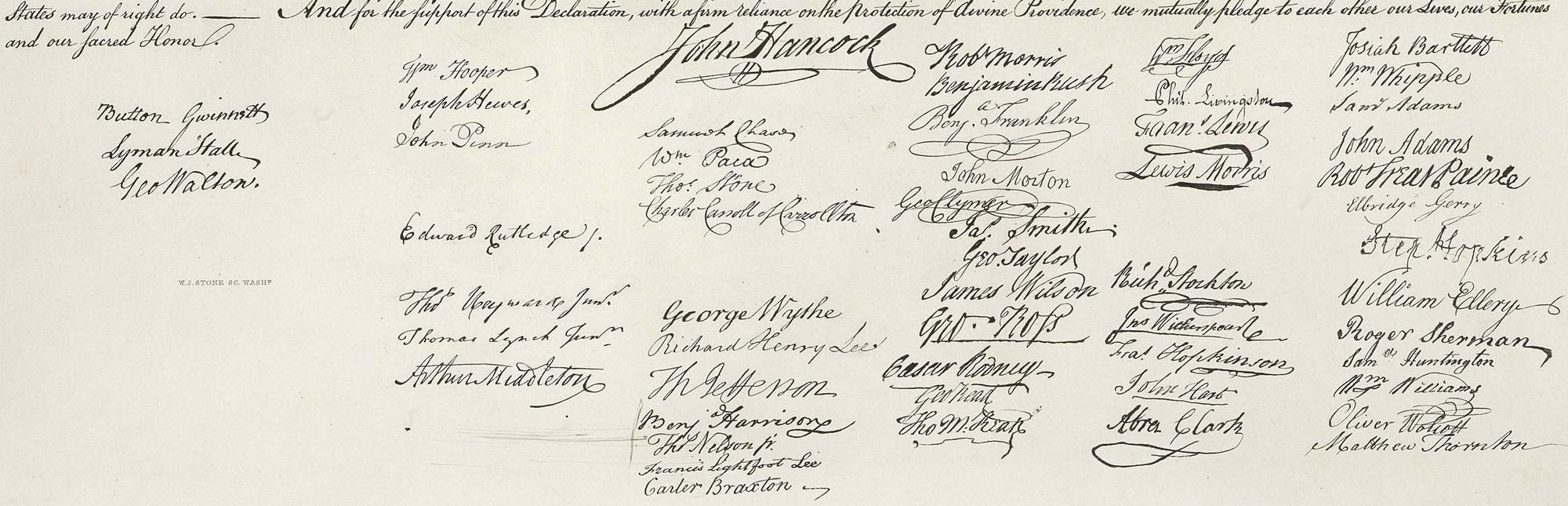

The signers are grouped by state, with the exception of President of Congress John Hancock, and the states are labelled. On the signed parchment of the Declaration of Independence, the signatures are more-or-less grouped by state, with the exception of Matthew Thornton, but the states are not labelled.

On the signed parchment, the states are in order from north (New Hampshire) to south (Georgia), and from right to left. This is why the New England signers are tightly grouped, while the Georgia signers are by themselves on the left side of the parchment.

Signed Parchment order, from left to right: NH, MA, RI, CT, NY, NJ, PA, DE, MD, VA, NC, SC, GA

GA | NC | MD | PA | NY | NH |

| SC | VA | DE | NJ | MA |

|

|

|

|

| RI |

|

|

|

|

| CT |

Goddard attempted to replicate the order of the signed parchment, but read the states from left to right instead of right to left. She begins with Georgia and ends with Connecticut.

Goddard's Order, from right to left: GA, NC, SC, MD, VA, PA, DE, NY, NJ, NH, MA, RI, CT

matches

Signed Parchment order, from left to right: GA, NC, SC, MD, VA, PA, DE, NY, NJ, NH, MA, RI, CT

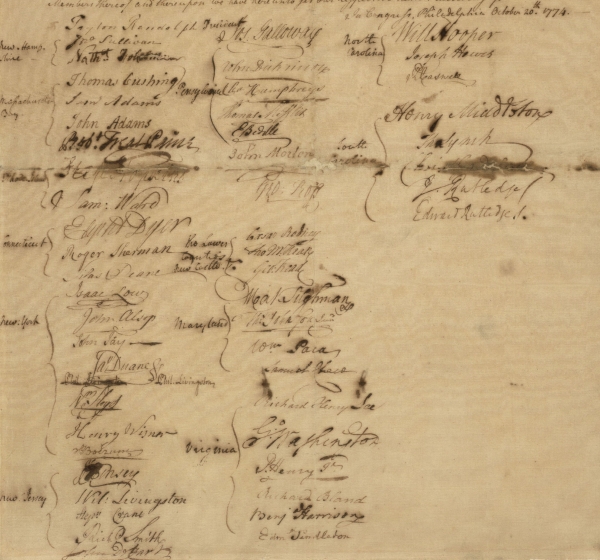

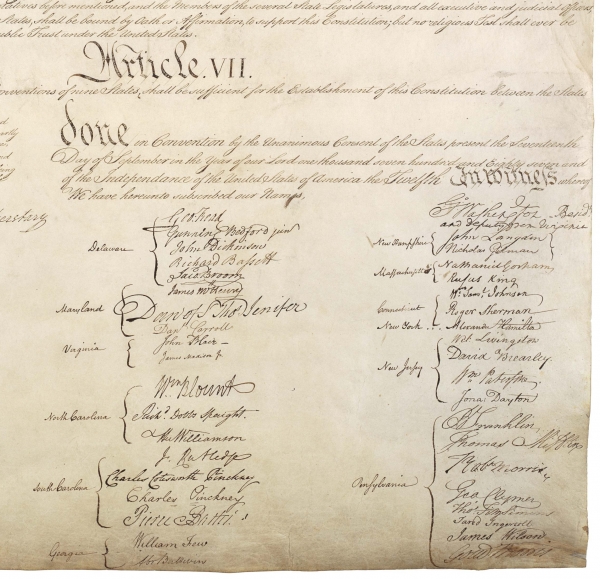

Goddard's error is totally understandable to English-speaking Americans who are used to reading from left to right. Her error is even more understandable in the context of earlier documents signed by delegates to the Continental Congress. In the Articles of Association (1774, below), Petition to the King (1774), and Olive Branch Petition (1775), the signatures are organized by state in order from north to south, and from left to right. The signed parchment Declaration of Independence represents a shift in practice, and later documents including the Articles of Confederation (1778-1781) and United States Constitution (1789, below) are organized by state in order from north to south, and from right to left.

Importantly, Goddard's error is also proof that she (or a clerk either working for her or the Congress) copied the names from the original signed parchment. In most printed versions of the Declaration to include the list of signers (all printed after January 1777, of course), the signers are organized by state and the states are labelled, but the printers intentionally listed the states from north (New Hampshire) to south (Georgia). These versions could have been copied from the signed parchment, but were more likely taken from the Goddard Broadside or the Journals of the Continental Congress for 1776, published in 1777 and 1778.

For More on Mary Katherine Goddard and the Goddard Broadside:

- There are ten existing copies of the Goddard Broadside at the following institutions, as well as one copy in private hands: Library of Congress, Connecticut State Library, John Work Garrett Library (Johns Hopkins University), Maryland State Archives, Maryland Historical Society, Massachusetts Archives, New York Public Library, Library Company of Philadelphia, Rhode Island State Archives, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- In 2009, artist Mindy Belloff recreated the Goddard Broadside and documented her effort.

- The Library of Congress has the only existing copy of another broadside printed by Goddard in December 1776, by order of Congress. The broadside is a letter from John Hancock and the Congress to the inhabitants of the United States, imploring them to keep the faith despite the British capture of Philadelphia.

- Goddard is featured on both the National Postal Museum's list of Women in the U.S. Postal System and the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame.

- For those familiar with Baltimore, the Rite-Aid at 125 E. Baltimore Street is the likely location of Goddard's print shop in 1777. Henry Fite House, where Congress met in 1777, was located in the block now occupied by Royal Farms Arena (formerly 1st Mariner Arena).

By Emily Sneff

Research Highlights | Next