Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was presented on June 7, 1776, it called for these three things, in this order:

Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was presented on June 7, 1776, it called for these three things, in this order:

-

That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be totally dissolved.

-

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

-

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

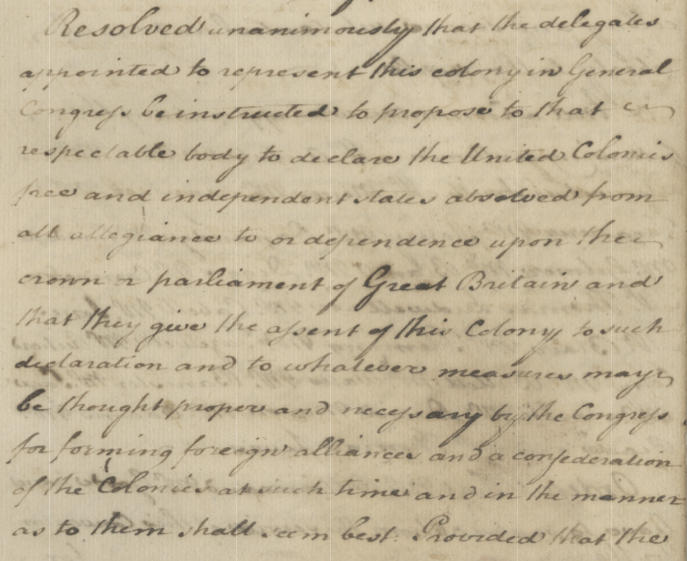

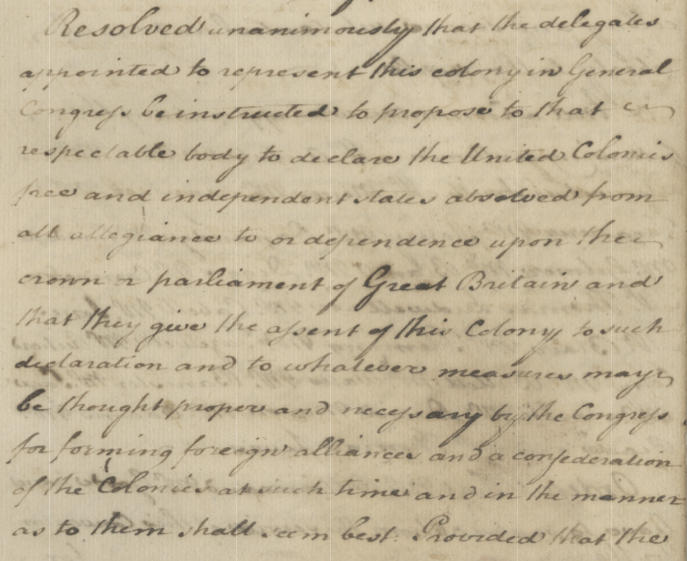

His resolution, or more accurately, his three resolutions were adapted from those of the Virginia Convention, agreed to on May 15: “Resolved, unanimously, That the Delegates appointed to represent this Colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain; and that they give the assent of this Colony to such declaration, and to whatever measures may be thought proper and necessary by the Congress for forming alliances, and a Confederation of the Colonies, at such time and in the manner as to them shall seem best: Provided, That the power of forming Governments for, and the regulations of the internal concerns of each Colony, be left to the respective Colonial Legislatures.”

Minutes of the Virginia Convention, Library of Virginia

The Journals of the Continental Congress show that these three resolutions occupied the debate on Saturday, June 8 and Monday, June 10. John Hancock even let George Washington know, “we have been two Days in a Committee of the Whole deliberating on three Capital Matters, the most important in their Nature of any that have yet been before us…” On the 10th, Congress resolved, “that the consideration of the first resolution be postponed to this day, three weeks, and in the mean while, that no time be lost, in case the Congress agrees thereto, that a committee be appointed to prepare a declaration to the effect of the said first resolution.” This pushed the discussion of independence to July 1.... Read more about Delegate Discussions: The Lee Resolution(s)

Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was

Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was

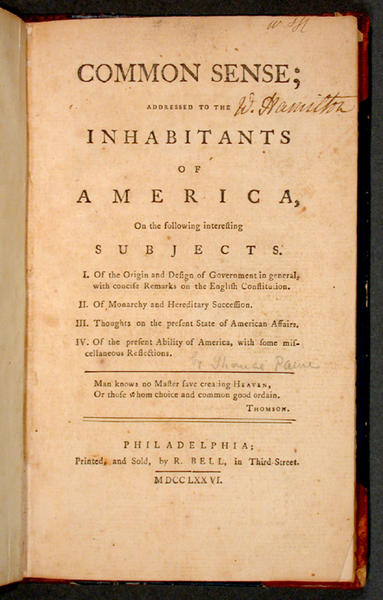

THIS day was published, and is now selling by Robert Bell, in Third-street (price two shillings) COMMON SENSE addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting SUBJECTS.

THIS day was published, and is now selling by Robert Bell, in Third-street (price two shillings) COMMON SENSE addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting SUBJECTS. Since it was first printed in Philadelphia, some of the first readers of Common Sense were the delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Some were thrilled by Common Sense, while others appreciated the section on American independence and dismissed the rest of it. As Steven Pincus explains in

Since it was first printed in Philadelphia, some of the first readers of Common Sense were the delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Some were thrilled by Common Sense, while others appreciated the section on American independence and dismissed the rest of it. As Steven Pincus explains in  On December 20, 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend James Madison. Living in Paris as United States Minister Plenipotentiary to France, Jefferson did not participate in the Constitutional Convention.

On December 20, 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend James Madison. Living in Paris as United States Minister Plenipotentiary to France, Jefferson did not participate in the Constitutional Convention.

Founding Fathers. Founders. Fathers. Founding Mothers. Signers. Framers. Patriots. The list of terms to describe the individuals who "founded" the United States of America can go on and on. This month, we examine the etymology and accuracy of these terms, and find where the signers of the Declaration of Independence fit in.

Founding Fathers. Founders. Fathers. Founding Mothers. Signers. Framers. Patriots. The list of terms to describe the individuals who "founded" the United States of America can go on and on. This month, we examine the etymology and accuracy of these terms, and find where the signers of the Declaration of Independence fit in.