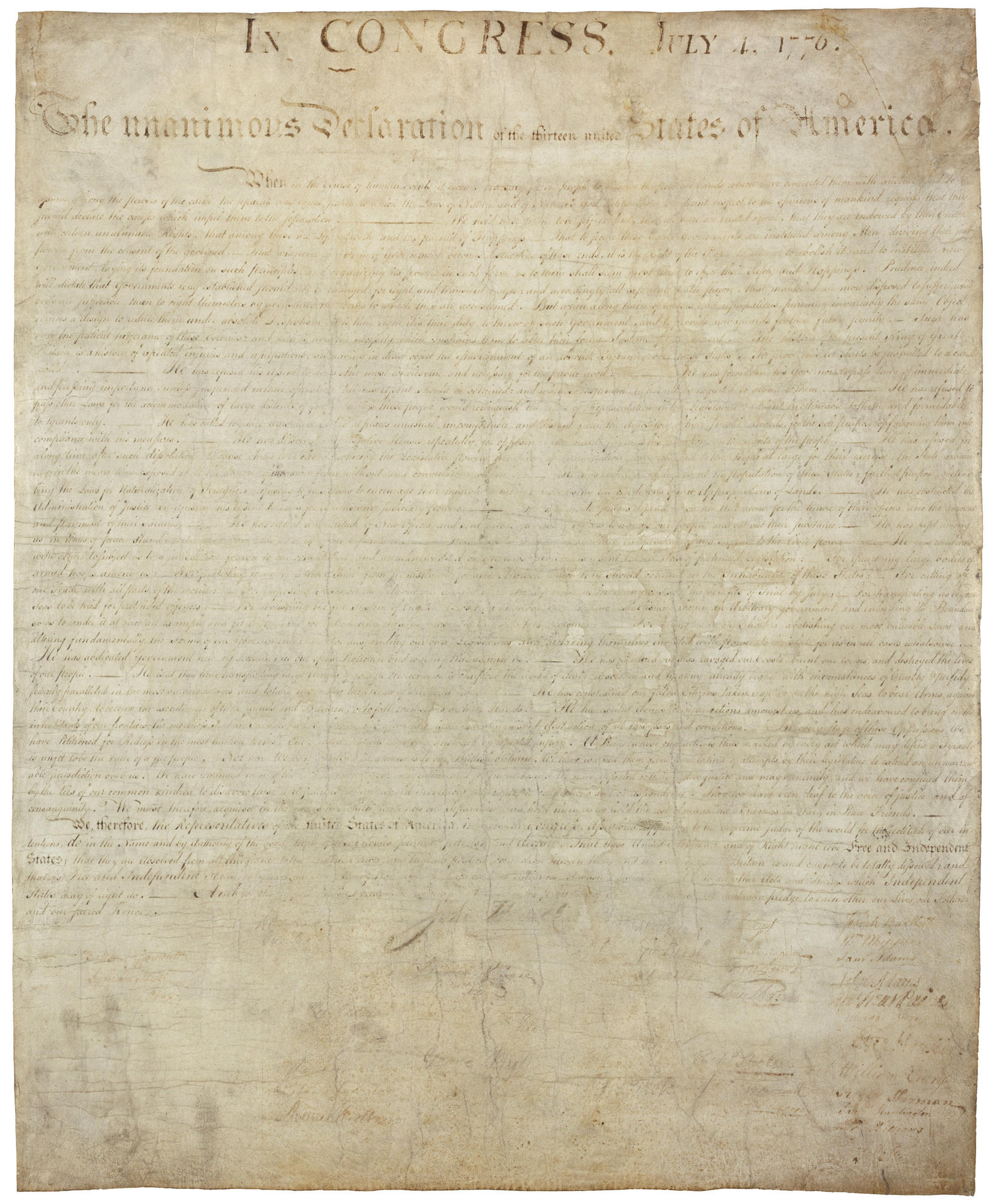

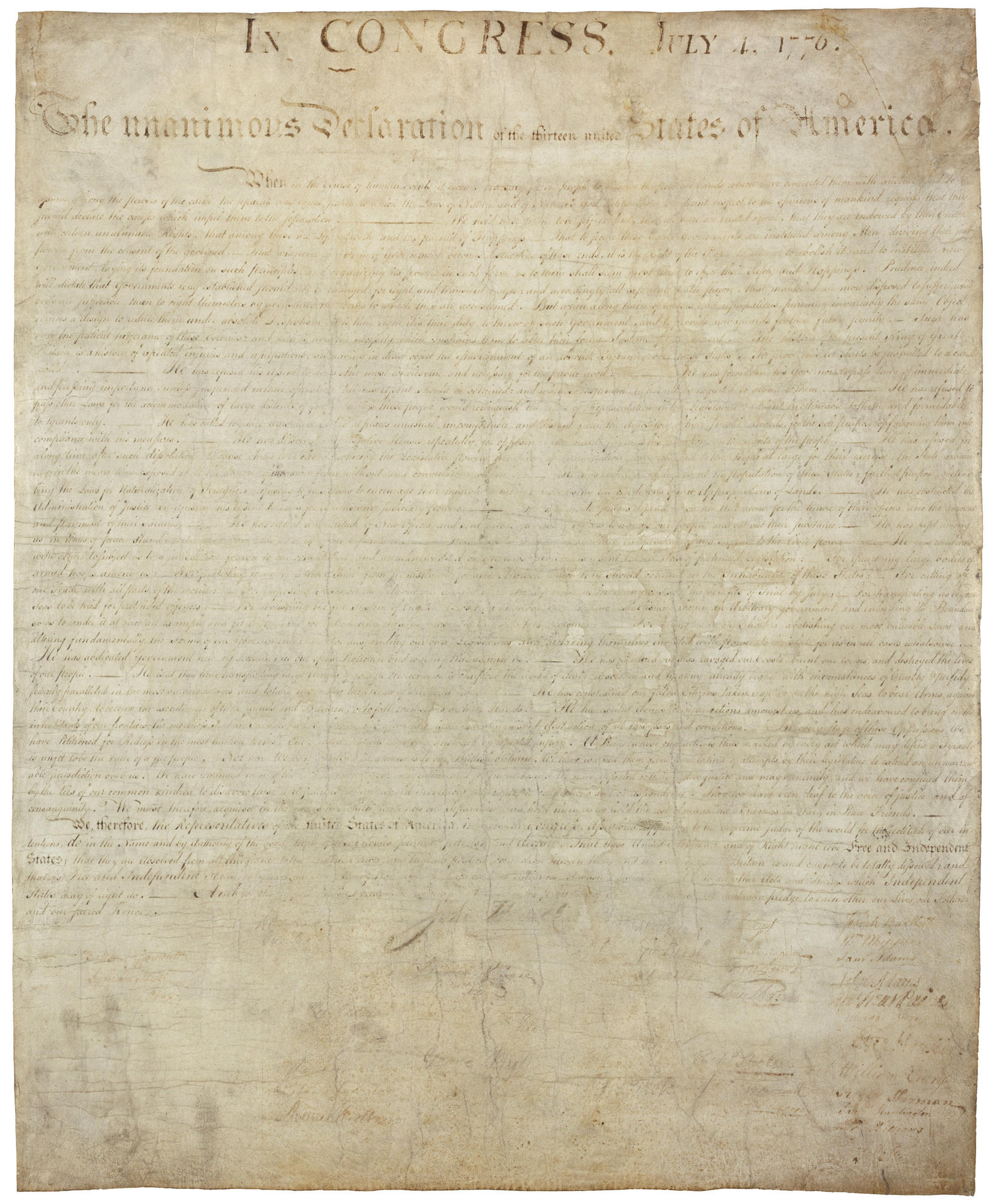

The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. This month, we trace the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. Stay tuned for part two (1877-today) in February!

The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. This month, we trace the engrossed parchment's physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. Stay tuned for part two (1877-today) in February!

1776

Continental Congress

Philadelphia

On July 19, 1776, the Continental Congress resolved, "That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Timothy Matlack likely took on this task, and on August 2nd, in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, the engrossed parchment was signed by the majority of the 56 delegates.

1776-1789

Continental Congress/Congress of the Confederation

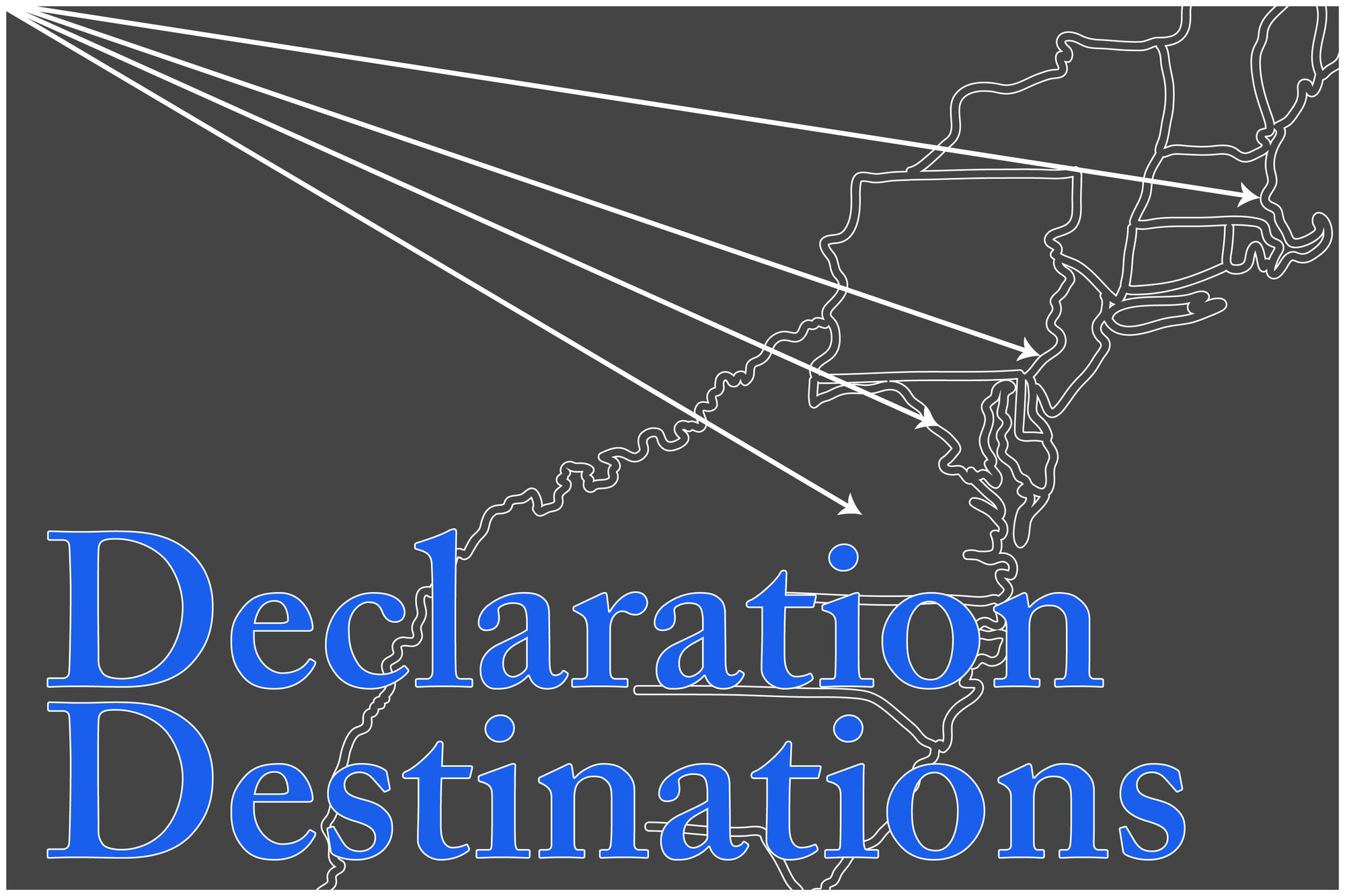

Philadelphia -> Baltimore -> Philadelphia -> Lancaster -> York -> Philadelphia -> Princeton -> Annapolis -> Trenton -> New York City

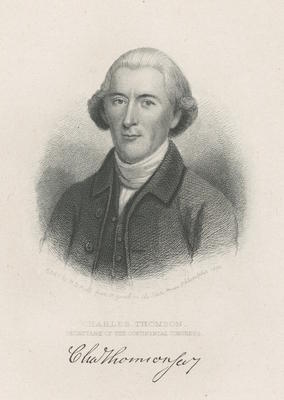

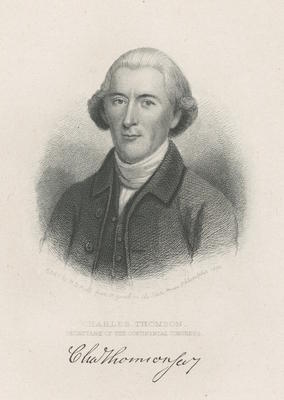

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (Image at right courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections). Thomson had been unanimously chosen as Secretary of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774. When the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775, Thomson was once again chosen as its Secretary. He stayed with the Congress as it transitioned into the Congress of the Confederation (under the Articles of Confederation), serving as secretary to the Congress for nearly 15 years, and counting among his responsibilities the care of the papers of the Congress (including the Declaration of Independence).

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (Image at right courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections). Thomson had been unanimously chosen as Secretary of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774. When the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775, Thomson was once again chosen as its Secretary. He stayed with the Congress as it transitioned into the Congress of the Confederation (under the Articles of Confederation), serving as secretary to the Congress for nearly 15 years, and counting among his responsibilities the care of the papers of the Congress (including the Declaration of Independence).

If the Declaration stayed with Thomson, then it is likely that it moved with the Congress, as he did. The first move came in December 1776, when the Congress evacuated Philadelphia and reconvened at the Henry Fite House in Baltimore, Maryland later that month. In January 1777, the engrossed parchment -- at least the signatures at the bottom -- likely served as a resource for Mary Katharine Goddard as she created her "authentic copy" of the Declaration. In March 1777, the Continental Congress returned to Independence Hall in Philadelphia, but only for a few months. In September 1777, Congress met for a day at the court house in Lancaster, Pennsylvania before moving further west to the court house in York, Pennsylvania. In July 1778, Congress returned to Independence Hall, this time for a few years. In June 1783, the Congress of the Confederation fled the Pennsylvania Mutiny and relocated to Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey. A few months later, in November 1783, the Congress reconvened at the State House in Annapolis, Maryland. In November 1784, the Congress met at the French Arms Tavern in Trenton, New Jersey for a month before adjourning and moving to New York. From January 11, 1785 through 1789, the Congress of the Confederation met in New York City, at City Hall (which later became Federal Hall) and at Fraunces Tavern.

Over the course of these thirteen years in the care of Charles Thomson, the engrossed parchment (assuming it stayed with the Congress through each of these moves) found a home in four different states, and spent a total of about six years at its first home, Independence Hall. The transition of custody that came with the establishment of the Federal Government would bring the Declaration back to Philadelphia and, ironically, back under the care of the man who drafted those engrossed words.

... Read more about January Highlight: Superintending Independence, Part 1

On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams implored her husband John to

On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams implored her husband John to  1744 - 1818

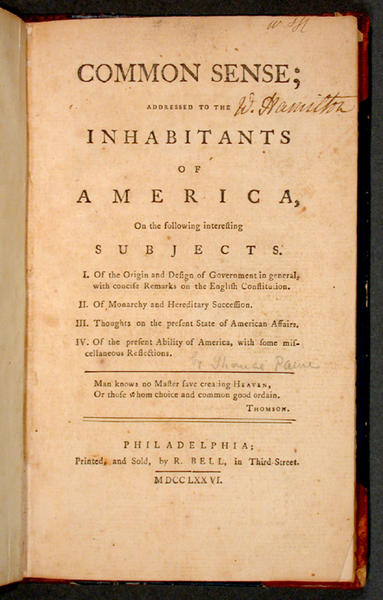

1744 - 1818 THIS day was published, and is now selling by Robert Bell, in Third-street (price two shillings) COMMON SENSE addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting SUBJECTS.

THIS day was published, and is now selling by Robert Bell, in Third-street (price two shillings) COMMON SENSE addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting SUBJECTS. Since it was first printed in Philadelphia, some of the first readers of Common Sense were the delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Some were thrilled by Common Sense, while others appreciated the section on American independence and dismissed the rest of it. As Steven Pincus explains in

Since it was first printed in Philadelphia, some of the first readers of Common Sense were the delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Some were thrilled by Common Sense, while others appreciated the section on American independence and dismissed the rest of it. As Steven Pincus explains in

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress ( In this edition of "Presenting the Facts", we explore John Adams, the 2008 HBO miniseries. The miniseries was based on the book of the same name by David McCullough; the screenplay was by Kirk Ellis, and it was directed by Tom Hooper. With one exception, we focused on the second half of Part 2: Independence (starting at 45:13). This episode is so richly detailed, we had to limit our analysis to just the events related to the Lee Resolution and the Declaration of Independence (sorry, Abigail!).

In this edition of "Presenting the Facts", we explore John Adams, the 2008 HBO miniseries. The miniseries was based on the book of the same name by David McCullough; the screenplay was by Kirk Ellis, and it was directed by Tom Hooper. With one exception, we focused on the second half of Part 2: Independence (starting at 45:13). This episode is so richly detailed, we had to limit our analysis to just the events related to the Lee Resolution and the Declaration of Independence (sorry, Abigail!).

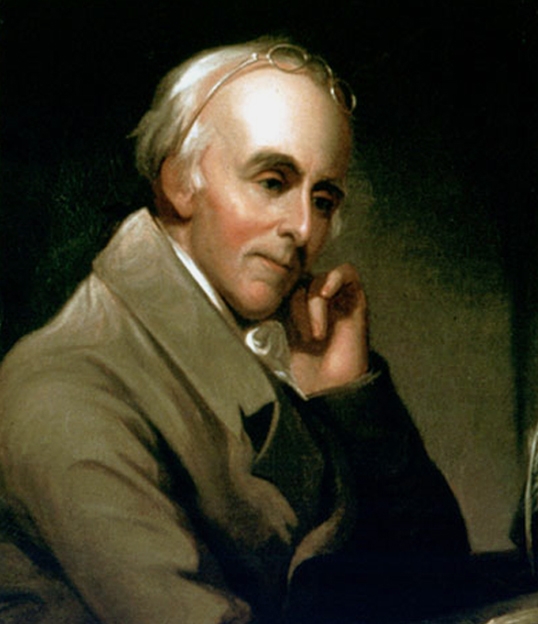

In February 1790, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote a

In February 1790, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote a

Last month, we debunked

Last month, we debunked