Last Updated: January 2018

There is no singular authoritative version of the Declaration of Independence. Most Americans and many historians consider "the" Declaration of Independence to be the engrossed and signed parchment, on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The image that comes to mind when most people think of the Declaration of Independence is actually the William J. Stone engraving of the engrossed and signed parchment. Every few years, when the story of a newly discovered copy of the Declaration of Independence surfaces, the copy is often a Stone engraving, or even a reprint of the Stone engraving by Peter Force. There are also rare newspaper editions where the text is condensed to the front page or spread out over multiple columns, manuscripts of typically unknown origins, and broadsides representing a small fraction of the number that were printed and proclaimed in the summer of 1776. So, when you see a copy of the Declaration of Independence, how do you know which version it is? And, why does that matter?

The Rough Drafts

The Rough Drafts

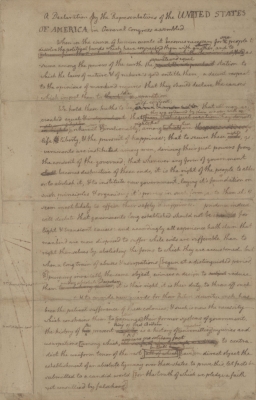

The "original" rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, in Jefferson's handwriting with passages scratched out and changed, is at the Library of Congress. They also have a fragment of what is thought to be the earliest draft of the document. While the Committee of Five was reworking the text and after they submitted it to the Continental Congress, Jefferson created "clean" copies of the original draft, as a record of the changes that were made by Congress. He sent these copies to his friends, including Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe, two Virginia delegates who were absent from the proceedings. Clean copies in Jefferson's hand are in the collections of the American Philosophical Society and the New York Public Library. There is also a draft in John Adams' hand at Massachusetts Historical Society, and a copy contained within notes Jefferson copied for James Madison in 1783 at the Library of Congress. These copies are similar to the final, approved version of the text, but should be considered their own documents, and not copies of the Declaration. For more information about the rough drafts, see Julian P. Boyd's The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text.

The First Official Printing: John Dunlap's Broadside

The First Official Printing: John Dunlap's Broadside

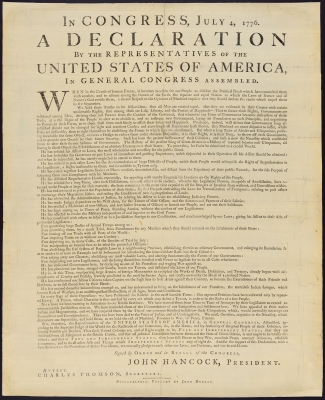

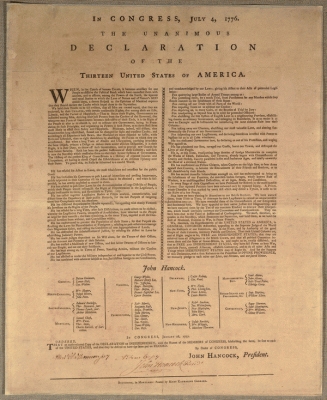

On the night of July 4th, Philadelphia printer John Dunlap was given the task of printing the first broadside of the Declaration of Independence. According to the Journals of the Continental Congress, the Committee of Five was responsible for superintending and correcting the press, and it is likely that a member of the Committee went to Dunlap's shop (more likely Adams than Jefferson, who was apparently buying ladies gloves on the 4th). The broadsides were printed by the next day, and distributed to the Committees of Safety in every colony as well as to the head of the Continental Army, General George Washington. Julian P. Boyd called the Dunlap Broadside the "second official version" of the Declaration, because a broadside was pasted into the Journals of the Continental Congress for July 4th. It was the first published version of the text, the first public version, and the version that most printers relied upon for their own editions of the text. In 1949, there were 14 extant copies of the Dunlap broadside. As of 2009, there are 25 existing copies, as well as a "proof" copy at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The following institutions and individuals have a copy of the Dunlap broadside, and some are on display from time to time, especially in exhibitions surrounding the 4th of July or the Founding Fathers.

Beinecke Library, Yale University (New Haven, CT)

Library of Congress (1 copy plus fragment copy; Washington, D.C.)

National Archives (Washington, DC)

Lilly Library, Indiana University (Bloomington, IN)

Chicago Historical Society (Chicago, IL)

Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, MA)

Houghton Library, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA)

Williams College (Williamstown, MA)

Maryland Historical Society (fragment; Baltimore, MD)

Maine Historical Society (Portland, ME)

American Independence Museum (Exeter, NH)

Scheide Library, Princeton University (owner: William R. Scheide; Princeton, NJ)

Morgan Library (New York, NY)

New York Public Library (New York, NY)

Private Collector (last known location: New York, NY)

American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia, PA)

Independence National Historical Park (Philadelphia, PA)

Dallas Public Library (Dallas, TX)

University of Virginia (2 copies; Charlottesville, VA)

Norman Lear et. al. (Roving)

The National Archives (3 copies; London, United Kingdom)

The First Unofficial Printing: Benjamin Towne's Newspaper

In 1776, most newspapers printed once a week, on a specific day. With his Pennsylvania Evening Post, Benjamin Towne created the first evening newspaper and the first tri-weekly paper in America. This gave him a huge advantage when it came to news items, including the Declaration of Independence. On July 2nd, since he printed in the evening, Towne was able to include a brief announcement in his newspaper: "This day the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES." On his next print day, Thursday the 4th, John Dunlap was still the only printer with the text of the Declaration. But by Saturday the 6th, Towne had gotten a copy of the text, and printed the Declaration of Independence as front page news, scooping Dunlap's own Pennsylvania Packet by two days (the Packet typically printed on Mondays). The text is similar to Dunlap, though Towne used less capitalization and he punctuated the second sentence differently. This first newspaper version represents the method in which many Americans would have read the text of the Declaration. Several institutions own the July 6, 1776 issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, and there are also a few copies in private hands.

Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.)

Lilly Library, Indiana University (Bloomington, IN)

Boston Public Library (Boston, MA)

American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA)

Clements Library, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI)

Gloucester County Historical Society (Woodbury, NJ)

Cornell University (Ithaca, NY)

New-York Historical Society (New York, NY)

New York Public Library (New York, NY)

State Library of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, PA)

American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia, PA)

Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA)

Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA)

Museum of the American Revolution (Philadelphia, PA)

Harlan Crow Library (Dallas, TX)

University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA)

Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (Oxford, UK)

A copy owned by David M. Rubenstein is on loan to the Newseum (Washington, D.C.) and will be on display through 2017 in the new exhibition "1776 - Breaking News: Independence".

Other Broadsides

After Dunlap, a number of printers created their own broadsides of the Declaration of Independence, sometimes for their own purposes and sometimes as an "official" state version. Broadsides are distinguishable from newspapers because they are one sheet, similar to a poster, and the printer would often include their name and the location of their print shop at the bottom of the sheet. In New York, John Holt printed a broadside that included New York's resolution in favor of independence, which made the Declaration unanimous. In Massachusetts, Ezekiel Russell printed a broadside that included the order for a copy to be sent to all the parishes in Massachusetts. These broadsides created by the printers listed below are typically even more rare than the Dunlap broadside, and some local institutions may display them from time to time.

Thomas and Samuel Green (New Haven, CT)

John Gill, and Powars and Willis (Boston, MA)

Ezekiel Russell (Boston, MA)

Hugh Gaine (New York, NY)

John Holt (New York, NY)

Steiner & Cist (German printing; Philadelphia, PA)

Solomon Southwick (Newport, RI)

Peter Timothy (Charleston, SC)

There are a handful of other broadsides printed in July or August 1776 without a printer's name. One has been attributed to Samuel Loudon in New York, another to either Ezekiel Russell or John Rogers working out of Russell's shop, and another to Robert Luist Fowle in Exeter, N.H.

Other Newspapers

After Towne's Evening Post, the Declaration of Independence was printed in five other newspapers in Philadelphia, and the text spread to newspapers throughout the United States (and eventually to England and Europe). Newspapers are distinguishable based on their header, and typically included 4-6 pages. The Declaration of Independence was usually but not always front page news, and very rarely fit entirely on a single page. These newspaper versions are occasionally displayed, but often kept in newspaper collections. Newspaper versions of the Declaration of Independence from 1776 include:

Hartford, CT: The Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer (July 15)

New Haven, CT: The Connecticut Journal (July 17)

New London, CT: Connecticut Gazette and the Universal Intelligencer (July 12)

Norwich, CT: The Norwich Packet and the Connecticut, Massachusetts, New-Hampshire, & Rhode-Island Weekly Advertiser (July 15)

Boston, MA: Continental Journal and Weekly Advertiser (July 17); The New-England Chronicle (July 18)

Newburyport, MA: The Essex Journal and New-Hampshire Packet (July 19)

Salem, MA: The American Gazette or the Constitutional Journal (July 16)

Watertown, MA: The Boston-Gazette and Country Journal (July 22)

Worcester, MA: The Massachusetts Spy or American Oracle of Liberty (July 17)

Annapolis, MD: The Maryland Gazette (July 11)

Baltimore, MD: Dunlap's Maryland Gazette, or the Baltimore General Advertiser (July 9); The Maryland Journal, and Baltimore Advertiser (July 10)

Exeter, NH: "Extraordinary" New Hampshire Gazette, or Exeter Morning Chronicle (July 16)

Portsmouth, NH: The Freeman's Journal or New Hampshire Gazette (July 20)

New York, NY: The Constitutional Gazette (July 10); The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury (July 15, New York, NY); The New-York Journal, or the General Advertiser (July 11); The New York Packet and American Advertiser (July 11)

Philadelphia, PA: Dunlap's Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser (July 8); Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (German printing; July 9); The Pennsylvania Gazette (July 10); The Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser (July 10); The Pennsylvania Ledger, or the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New-Jersey Weekly Advertiser (July 13)

Newport, RI: "Extraordinary" The Newport Mercury (July 18)

Providence, RI: The Providence Gazette and Country Journal (July 13)

Charleston, SC: The South Carolina and American General Gazette (August 14)

Williamsburg, VA: The Virginia Gazette (Printed by Dixon & Hunter; July 20); The Virginia Gazette (Printed by Purdie; Extracts on July 19, Full text July 26)

The Signed and Engrossed Parchment

The Signed and Engrossed Parchment

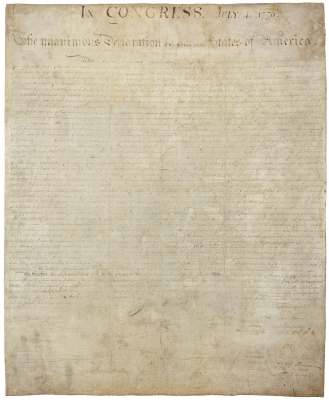

After the Declaration of Independence was approved by Congress, it was ordered to be engrossed on parchment and signed by the delegates. The engrosser was most likely Timothy Matlack, one of Secretary Charles Thomson's assistants. Matlack completed the parchment by August 2nd (with only two corrected errors), and the delegates commenced with signing. Many signatures were added on August 2nd, and the rest were added in the coming months as delegates returned to or arrived in Philadelphia (Thomas McKean's was the last signature added, sometime between 1777 and 1781). The parchment was entrusted to Thomson, was rolled up with other documents, and traveled with the Continental Congress as they moved locations over the course of the Revolutionary War. It was then entrusted to the office of the Secretary of State; the first, ironically, being Thomas Jefferson. In the 20th century, custody transferred to the Library of Congress, and then to the National Archives. Today, you can see the now-faded parchment at the National Archives, along with the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Manuscript Copies

Manuscript copies of the Declaration of Independence (distinct from the rough drafts and clean copies) are simply handwritten copies of the final, approved text. The most authoritative manuscript copy is in the original Journals of the Continental Congress, in Charles Thomson's hand. The exact provenance for most other manuscript copies is unknown, and speculation over the handwriting and timing of these documents is typically their most intriguing feature. The Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, OK has a manuscript copy signed by Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. The Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI has two manuscript copies in the papers of George Sackville Germain, who was the British Secretary of State for the American Colonies during the Revolutionary War. The Parliamentary Archives also have a manuscript copy of the Declaration, dated January 20, 1778, which was laid before the House of Lords as part of a peace enquiry which was defeated on February 2nd.

Another "official" broadside was created six months after Dunlap's first broadside, while the Continental Congress was meeting in Baltimore. The Goddard Broadside, printed by female printer and postmaster Mary Katherine Goddard, was the first to include the names of the signers (minus McKean). This was a more limited print run than Dunlap's, and broadsides were sent to each of the states for their official archives. In 1949, nine copies of the Goddard broadside were known (there may be more in existence), and were located at the following institutions.

Connecticut State Library (Hartford, CT)

Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.)

Massachusetts Archives (Dorchester, MA)

Maryland Hall of Records (Annapolis, MD)

Evergreen Library, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD)

New York Public Library (New York, NY)

Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA)

Rhode Island State Archives (Providence, RI)

Later Engravings

Later Engravings

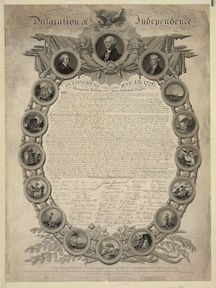

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned William J. Stone to create an engraving of the engrossed and signed parchment, which was already fading. Stone completed his engraving by 1823, and 200 copies of the Stone engraving were printed. Stone's engraving is the basis for most reproductions of the Declaration of Independence today. His engraving was also used by Peter Force to create another set of printings in connection with Force's American Archives series.

Other engravers approximated the engrossed and signed parchment in the early 19th century, including Benjamin Owen Tyler, John Binns (pictured), and Eleazer Huntington. After Stone's printing became the relied upon "exact facsimile", printers seemed to take the opportunity to create more decorative printings (more in the style of Binns' engraving), often including portraits of the signers, symbols for the thirteen states, and patriotic icons such as the Liberty Bell, bald eagle, or George Washington.

If you see a Stone engraving (or find one in your attic or the back of a picture frame...) and wonder if it is authentic, follow these guidelines or consult with an appraiser or historian.

These later engravings are good resources for the text of the Declaration of Independence, but they are very rarely exact facsimiles of the engrossed and signed parchment.

Why Does It Matter?

Almost every version of the Declaration of Independence printed or written in 1776 was different from the next in terms of punctuation, capitalization, or errors. This continued through book printings and newspaper re-printings in the late 18th and 19th century. The Dunlap broadside differs from the Towne newspaper, differs from the engrossed and signed parchment, differs from the Goddard broadside, and so on. Even the engrossed and signed parchment differs from the Stone engraving. The most important thing is to read the text of the Declaration of Independence. Seek out an exhibition of "a copy of the Declaration of Independence", or search for one online. But once you have finished, consider where the copy you just read came from, and how it relates to the complex textual tradition of the Declaration.